Ever wondered what was the story behind the name “Pring” (made famous in the “This is Singh and Pring” poster) ? Joydeep Sircar takes you through the life of Flt Lt A M O Pring, who captured the imagination of the people of Calcutta…

Ever wondered what was the story behind the name “Pring” (made famous in the “This is Singh and Pring” poster) ? Joydeep Sircar takes you through the life of Flt Lt A M O Pring, who captured the imagination of the people of Calcutta…

War came to Calcutta on the night of the 20th December, 1942.

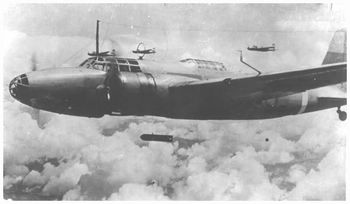

The Japanese had overrun Burma by May 1942, chasing the tattered remnants of British-Indian and Chinese troops across the jungle-clad hills of the Indo-Burma border, but they were not strong enough to push on into India. But Calcutta lay well within the range of their bombers, and what the people of the city had been fearing ever since the fall of Burma came to pass on the 20th of December. A force of eight Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF) Ki -21 Type 97 medium bombers, code-named ‘Sally’ by the Allies, scattered their bombs over the city. They damaged the oil plant at Budge Budge, located on the Ganges river a little South of the city, and one eyewitness reported a hole in the road opposite the Great Eastern Hotel, but the physical damage inflicted on the city was trivial compared to the devastating blow to the morale of the inhabitants: approximately one-and-a-half million people panicked and fled, among them a majority of the conservancy workers who hailed from upcountry villages. The effect on the civic services was catastrophic, and there were serious fears of an epidemic caused by the mounds of rotting garbage that accumulated. The IJAAF bombers returned on a number of occasions on the days that followed, notably on the night of the 24th December. This Christmas Eve raid by 10 Sallys achieved a scattering of bombs over the Chowringhee- Bentinck Street- Dalhousie Square area of Central Calcutta and caused some loss of life, thus considerably dampening the Yuletide cheer.

At that time India had little or no defence against night air attacks. Britain’s main focus was on Europe and the Middle East, and India was, till 1941, a peaceful backwater where obsolete and obsolescent aircraft types could be put out to grass. Westland Wapitis and the like were perfectly adequate for carrying out the occasional punitive raid on fractious Pathans of the NWFP. But all that changed with dramatic suddenness once Japan entered the war. The ‘sahibs’ who had been pompously dismissive about Japanese air power suddenly found that Japanese aircraft were not copies of outdated Western types but extremely effective original designs, and they were flown with aggressive elan by very skilled pilots who had honed their fighting edge in the skies of China and Khalkin Gol. In particular, the Mitsubishi A6M Type 0 ‘Zero’ fighter flown by pilots of the Imperial Japanese Naval Air Service (IJNAS) proved to be an outstanding aircraft that quickly gained a fearsome reputation. The Zero and it’s IJAAF cousin, the equally nimble if less well-armed Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa (codenamed ‘Oscar’) fighter swept the skies of Asia clean of all opposition barring Chennault’s American Voluteer Group (AVG). For the Royal Air Force and other opponents of the Japanese, it was, as Christopher Shores and his co-authors named their authoritative account of this period of the air war in Asia, ‘Bloody Shambles’.

To strengthen India’s air defences, particularly around Calcutta, a number of Hurricane squadrons were rushed out, and airfields came into being all around the city. The most famous and visible one of these airstrips was a 1100 yard section of the Red Road, between Chowringhee and the Maidan. It was not an easy strip to operate from due to the camber of the road surface and the ornamental balustrades that flanked the road on both sides, and there were occasional mishaps, but the pilots enjoyed using the restaurants lining Chowringhee as their Ready Room, and the sight of fighters operating from the heart of the city did much to improve the morale of the citizenry. And morale did need improving, for the news was not good. To add to the successive disasters of Malaya, Singapore and Burma, there was the tremendous scare of the arrival of Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s formidable fleet in the Bay of Bengal and neighbouring waters in April 1942. Aircraft from Nagumo’s fleet, which had wreaked havoc on the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, made short work of those unlucky ships of the Royal Navy which had not succeeded in fleeing West towards Africa, savaged the harbours of Ceylon after brushing aside the Hurricanes and Fairey Fulmars that tried to oppose them, and dropped the first bombs on India in WW2, hitting Kakinada and Vishakhapatnam on 6th April 1942.

They missed a plum target due to lack of intelligence. Some 250,000 tons of merchant shipping was sheltering in Calcutta port, which was already coming within range of Japanese airfields in South Burma. The Japanese had occupied the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in March 1942, and by April moved around 18 Kawanishi H6K ‘Mavis’ long-range flying boats of the Toko Kokutai to Port Blair, aircraft easily capable of reconnoitering Calcutta. In a desperate bid to blind the enemy, two Lockheed Hudson bombers from 139 Squadron flew from Calcutta to Akyab on 14th April, refuelled there, and then made the long overwater flight to hit the flying boat base. The low-level strike destroyed 3 aircraft and damaged 11 others. The raid was repeated on the 18th. Pressing home their attack at a height of only 30 feet, the Hudsons destroyed 2 more aircraft and damaged 3, but this time they were intercepted by fighters . Only one Hudson, badly damaged, returned. The crew of the other Hudson, flown by Sgt. G.H. Jackson, were taken prisoner. But they had crippled the Japanese long-range recce force, and some 70 merchantmen succeeded in safely sailing out of Calcutta and dispersing.

Calcutta’s luck had held in April, but it ran out in December 1942. The defending Hurricanes took off, the ack-ack guns fired noisily, but though Wing Commander Tony O’Neill, the Commanding Officer of 165 (Hurricane) Wing, claimed to have damaged one Sally on the 23rd, and actually shot one down on the Christmas Eve raid , a success widely publicized, it was clear that Calcutta was virtually defenceless at night.

But Britain did have the antidote to nocturnal raids, something she had developed painfully in the flaming nights of the Luftwaffe’s blitz against London : radar-guided ground-controlled interception of intruders by radar-equipped night-fighters. Guided by the ground controller to a position near the enemy aircraft, the night-fighter was able to ‘acquire’ the target on it’s onboard radar screen, and the radar operator (observer) could then guide the pilot to where he could see the enemy and shoot it down. The best of the night-fighters turned out to be a biggish twin-engined aircraft based on the Bristol Beaufort torpedo-bomber. Called the Beaufighter ( Beaufort + fighter), it was anything but ‘Beau’ in appearance, being snub-nosed and portly, but it had room enough to carry the AI (Air Intercept) radar and an observer, and also the awesome armament of four 20 mm cannon and six .303 machine-guns – firepower that was necessary to deliver a lethal burst in the very short engagement period usual in night interceptions.

Powered by 1500hp Bristol Hercules engines, it was just fast enough (c.330 mph) for the job. Flown by skilled night-fighter pilots like Cunningham, the Beaufighter defeated the Luftwaffe’s night bombers over Britain, and by 1942 was carrying the fight to the enemy, flying night intruder missions over enemy bases. A number of Beaufighter squadrons went to the Middle East. One such squadron was no. 89 in Egypt, which had a detachment flying intruder missions out of Malta. As an immediate response to the outcry that arose after the December raids on Calcutta, 89 Squadron was asked to detach a flight of Beaufighters to India to defend the city.

Eight Beaufighters (or five – sources differ), a mix of Mark 1F and Mark 6F types (the latter had 1670 hp Hercules engines but still carried the AI Mark 4 though other 6Fs were already flying with centimetric radar) made their way to Calcutta in stages, arriving at Dum Dum around the 12th of January 1943. On the 14th a new Royal Air Force unit, No. 176 Squadron, was raised from the nucleus of this detachment. The squadron letters were AS, and the motto chosen for the new formation was a very appropriate one : Nocte custodimus – ‘We keep the night watch’. Veteran pilot Wing Commander Tony O’Neill, whom we have met earlier, was appointed the first CO. This was a rather unusual step – Wing Commanders actually commanding a Fighter Wing are not usually asked to take up a Squadron Leader’s job – but the fact that O’Neill had flown night combat missions as a Beaufighter pilot in England may have had something to do with it.

[There is an interesting piece of aviation history here which deserves mention. 176 Squadron was raised at Dum Dum, it’s principal task for much of it’s existence was the protection of Calcutta, it served only in SE Asia, and it was disbanded at Baigachi in May 1946 : thus it can reasonably be called the Calcutta Squadron.]

176 may have been a newly minted squadron, but it’s aircrew were already old hands at the night interception game. One pilot, the Australian Flying Officer Charles Crombie, had already scored nine confirmed victories. Another rising star was an Englishman with a boyish, smiling face, born in Ealing, West London to Arthur Benjamin Pring and his wife Doris Lilian Pring (nee Garrett) on November 1, 1921. He wore the uniform of a Flight Sergeant , and his name was Arthur Maurice Owers Pring.

Pring’s father was an electrical engineer, and spent many years of his service career travelling around South America and Canada. After his return to England the Pring family moved from Ealing to 38, Ashlyns Road, Berkhamsted sometime between 1933 and 1937.

[ The above information was kindly provided by Ms Jenny Sherwood of Berkhamsted. ]

Maurice Pring was called up from university in 1940 and selected for night fighter pilot training. On completion of training he was first posted to 604 Squadron (Beaufighters). By June 1941 he was in 125 Squadron (Defiants, then Beaufighters), and in early 1942 he was transferred to 89 Squadron based in Egypt (Beaufighters). Here he teamed up with his observer, Warrant Officer C.T. Phillips. Pring damaged a Heinkel He.111 on the night of 3 / 4 July and achieved his first victory on the night of 4 / 5 July 1942 – another Heinkel over Suez. Posted to C Flight at Malta, he destroyed two bombers, an Italian CANT Z1007 bis and a German Heinkel He.111, over Castelvetrano airfield, Sicily, on the night of October 12 /13 ,1942. On the night of the 19 / 20 October he added a Junkers Ju.88 to his tally – his fourth victory. Two nights later he claimed a He.111 as damaged – postwar research shows his victim was possibly a Fiat BR20M of the Regia Aeronautica’s Gruppo 88 which was so badly damaged that it’s crew baled out and the plane crashed at Nisceni in Sicily. At that point Pring’s official score stood at four victories (plus two probables).

During World War One the French first used the term ‘ace’ to describe a skilled pilot, and it speedily caught on among the Allies. It came to mean a pilot who had achieved five or more victories in aerial combat. On 14th January 1943, Maurice Pring was just one victory away from becoming an ace.

176 Squadron was not formed a day too soon, and achieved the rare distinction of seeing action the day after it had been raised. The IJAAF came back to Calcutta on the night of 15th January 1943. When the raid warning came Pring and his observer W/O Phillips headed towards their Beaufighter 1F no.X7776 ‘M’ together with armourer LAC Carl Morgan. As they neared it they were brought up short by a sharp ‘Halt!’ from an African soldier guarding the aircraft. Asked by the sentry to give the password, the bewildered trio realized they did not know it, and prudently retreated when the guard operated the rifle bolt to chamber a round. Luckily they found the officer in charge of the guard detachment in a nearby tent, and were eventually allowed into their aircraft just before the order came to scramble!

|

| Beaufighter 6Fs of 176 Squadron being readied for night standby,Baigachi, early 1943. AMO Pring sometimes flew X7682 ‘A’ on the right. [Photo P G Hill courtesy Andy Thomas] |

Airborne at about 2145, Pring was vectored towards the raid. In the brilliant moonlight, the three unpainted Ki-21 Sallys of the 98th Sentai piloted by Capt. J. Takita, Capt. K. Tanaka and Lt.(junior grade) J. Ishida seemed to ‘gleam like silver fishes’ to one onlooker. Pring intercepted , and destroyed all three in just four minutes. The combat took place about 20 miles South-South-West of Khulna, roughly 70 miles East of Calcutta. There was no return fire from the Japanese gunners.

|

| Mitsubishi Ki 21-1 Sally – Pring shot down three of these in one night |

The story broke widely, first in the local papers of the 16th, both English and vernacular, followed by coverage worldwide. The official communique mentioned only that Pring had been flying a ‘British fighter’, not specifying the actual aircraft type so as to keep the enemy unaware of the arrival of the Beaufighter. This led to the widespread but erroneous impression that he had been flying a Hurricane, which was the only type of fighter the populace were familiar with. Even my late father Pradipta Kumar Sircar, a profoundly knowledgeable aviation enthusiast, told me Pring was a Hurricane pilot.

Pring must have been very pleased to join the elite ranks of fighter aces, but he cannot have anticipated the instant fame that came his way. The Statesman, the leading English daily of Calcutta, carried the account of Pring’s combat the next day together with a full page war loan advertisement featuring Pring with the legend “Lend to be free. Be like Sergeant Pring, put all your efforts behind the fight against the enemy. Bravo Pring.” The powers-that-be had found in the photogenic fighter pilot their poster boy. This particular advertisement was repeated on a number of occasions thereafter.

The RAF immediately awarded Pring the Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM) and Phillips the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) – Pring did not get the DFC because class-conscious Britain gave DFCs only to Warrant and Commissioned Officers! Ironically, he was commissioned as Pilot Officer on promotion effective 21st January.

[The official communique about Pring’s feat mentioned that he had three victories earlier, and the notice of Pring’s DFM award in FLIGHT [April 1,1943, p. 350] gave Pring’s confirmed score as 6. However, Andrew Thomas’s authoritative BEAUFIGHTER ACES OF WORLD WAR 2 [Osprey Aircraft of the Aces 65, 2005] credits Pring with 7 confirmed victories (plus 2 probables). In personal communications Andrew was kind enough to give me precise details regarding Pring’s victories, quoting ACES HIGH by Christopher Shores and Clive Williams [Grub Street 1999]. I also owe to him important details regarding 176 Squadron and Pring’s last flight , and permission to use photographs from his book .

All Pring’s decorations – DFM , 1939-45 Star, Air Crew Europe Star, Africa Star with clasp North Africa 1942-43, Burma Star, and War Medal – was put on auction by Dix Noonan Webb as Lot 568 of 30th June 1998 (expected price GBP 2500-3000) and was sold for GBP 2500.]

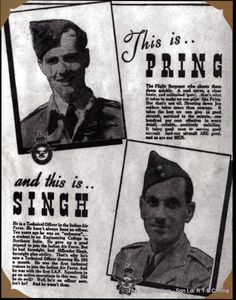

But rarer distinction awaited Pring : his photograph was chosen to appear on an Air Force recruiting poster . The text said, in part – “This is PRING The Flight Sergeant who shoots them down quickly. A cool nerve, a clear brain, and unlimited ‘guts’, that’s what it takes to make an ace pilot like Pring. —-”

[From HURRICANE OVER CALCUTTA by David McMahon in Anglo-Indian Portal.]

|

| This Recruitment Poster for the airforces in India, made famous by the photos of Pring and Plt Offr Harjinder Singh, was designed to capture the imagination of the youth and motivate them to join the Indian Air Force. Photo Courtesy: The Eagle Strikes |

Pring became the toast of Calcutta, being much in demand in civil and military dinners, and gaining a fan following long before the term became current, particularly among children and the teenagers, his boyish good looks doing no harm at all. Carl Morgan in his memoir STRANGERS IN THE SKY (Forces Publishing Service, 1995) recounts an anecdote that is illustrative: on 21st January Pring , Morgan and others went by ‘gharry’ (vehicle) from Dum Dum to Calcutta. Pring wanted to buy a .22 rifle for hunting in the jungles around camp, and went to a gunshop in the Chowringhee area. He found one fitted with a telescopic sight that he liked. On being told the price, he regretfully remarked that it was beyond his budget, and he would have to go for something more modest. A well-dressed Indian gentleman who was present in the shop then asked him if he was the Sergeant Pring who shot down three Japanese bombers in four minutes. On Pring answering in the affirmative, the gentleman asked the shop owner to pack the weapon and 2000 rounds of .22 ammunition for Pring, and paid for it. He then took Pring in his Rolls-Royce to the Police Commissioner for a gun license ( which Pring did not require as a member of His Majesty’s Forces), and finally to Firpo’s for a ‘slap-up meal’ before dropping him at the ‘gharry pick-up point’ for going back to Dum Dum!

Undeterred by the loss of the entire raiding force on the 15th, the IJAAF mounted another raid with four Sallys on the night of January 19, 1943 . This time they ran into the Australian night-fighter ace Charles Crombie and his observer W.O. Raymond Moss in Beaufighter 6F [X8164] ‘G’ above Budge Budge at around 2045. This time the dorsal and tail gunners of the Sallys were not caught napping, and their shooting was accurate. Despite his starboard engine being set on fire, Crombie destroyed one bomber, ordered Moss to bail out as flames streamed from his wing, and continued attacking, destroying a second Sally and heavily damaging a third for a probable. He baled out with his clothes alight seconds before the Beau’s fuel tank exploded, landed in a swamp, and made his way back to Dum Dum.

A piece of duralumin from one of his victims that crashed near Falta lay for decades among the junk in our garage till it was used to block a hole much favoured as a passage by our neighbourhood rats. We could hear them gnawing away for days at that piece of metal with their formidable incisors before they gave up – possibly due to toothache?

Crombie won an immediate Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and Moss the DFC for this action. Crombie also got the DFC in May 1943 for his service with 89 Squadron in the Middle East. He left for Australia in July with his score standing at 11 (plus 3 probables), and survived the war, only to die tragically while air-testing a Beau on 26th August 1945.

|

| Flying Officer Charles Crombie (right) with his 176 Squadron CO, Wg Cdr Tony O’Neill [Photo J A O’Neill courtesy Andy Thomas] |

The savage losses suffered by IJAAF night raiders at the hands of Pring and Crombie led to the suspension of the Japanese raids against Calcutta for eleven months. The city welcomed the respite, and those who had fled in panic after the December raids came trickling back.

In February 1943 176 Squadron moved from Dum Dum to Baigachi airfield, some 40 miles North East of Calcutta. The pilots became adept at covering the distance between Baigachi and their favourite watering holes around the Chowringhee area in an alarmingly short time.

In May 1943 the squadron received reinforcements of a distinctly dubious nature : a flight of Hurricane 2C aircraft equipped with pilot-operated AI (Mark 6?) radar. The Hurricane, obsolete as a day fighter, had won some renown as a night intruder at the hands of pilots like Kuttelwascher. Now it was to be tried out as a night-fighter. It looked suspiciously like a lash-up job : one source describes it as having an underwing-mounted Type 69 transmitting dipole from a Mosquito outboard of the cannons,Type 29 unipole arrays for elevation from the Defiant night-fighter,and vertically polarised azimuth dipoles from the Fulmar night-fighter. It was true that 245 Squadron in England had operated this aircraft, called Hurricane IIC (AI), on convoy patrol duties [some ex-245 aircraft came to 176], but to 176 Squadron fell the unenviable distinction of taking this machine into battle. There were good reasons for reservations. The performance of the Hurricane IIC, already inferior to contemporary frontline day fighters, was further degraded by the weight and the drag of the radar installation. And the feasibility of the pilot operating the radar set while flying night combat was in doubt.

Maurice Pring learnt to fly the Hurricane, but he cannot have been too impressed with them, considering that the night-fighter version of the potent De Havilland Mosquito had become operational more than a year ago in Europe. It was a pointed reminder of the fact that South-East Asia Command enjoyed the distinction of having the lowest priority among all combat theatres. No wonder Gen. Slim told his men “You are, and will remain, the Forgotten Army.”

Pring’s promotion to Flying Officer came through on 21st July 1943. In August the Beaufighter 1Fs were replaced by 6Fs . 176 sent detachments to Madras and Ratmalana in Ceylon to offer protection against raids, and a Beaufighter from Ratmalana flown by Flt. Sgt. L. Atkinson and Flt. Sgt. W. Simpson scored the next victory for 176, shooting down a Mavis flying boat from the Andamans on 11th October 1943 after a long chase.

Spitfires arrived at last in India in August 1943 – only Mark 5Cs, but still welcome as they could intercept and destroy the Mitsubishi Ki-46 ‘Dinah’ recce aircraft which had hitherto flown too high and too fast for the Hurricanes. 607 and 615 Squadrons gave up their Hurricanes and converted to Spitfires, followed by 136. In October Spitfires units began moving forward to Chittagong and Ramu to assist in operations over the Arakan and provide a forward defensive screen against Japanese air incursions. The tactic appeared to succeed, but the wily Japanese were not quite done with Calcutta yet. They planned their next strike well.

With the Spitfires gone, Operations had asked 176 on 4th December if their Hurricanes could intercept a fast, high-flying Ki-46 Dinah which had come over that day. To enable the Hurricane 2C (AI)s to climb high enough and fly fast enough to do so if the Dinah reappeared on the 5th, they were stripped of radar and armour to lighten them.

In the morning of Sunday,5th December 1943, two Beaufighters of 176 had scrambled after a lone Dinah which flew out of range. The day promised to be peaceful – until warning came in of a large raid. Uniquely, the Japanese were coming in broad daylight, in real strength, and this was a combined effort by the Army and Naval Air Forces. In the IJAAF first wave were 18 Ki-21 Sallys protected by no less than 74 Oscars of the 33, 50 and 74 Sentai. More Oscars from the 204 Sentai covered the withdrawal. In the IJNAS second wave, 9 G4M ‘Betty’ bombers of the 705 Kokutai were being escorted by 27 Navy Zeroes from the 331 Kokutai.

Taking advantage of their inherent long range ability, the Japanese formations had flown far out into the Bay of Bengal , beyond the range of the screening Spitfires of 136, 607 and 615 squadrons which turned back after vainly trying to intercept. Flt. Lt. Eric ‘Bojo’ Brown from 136 was the only Spitfire pilot to find the Japanese, having ignored the recall order, and he claimed a Sally. The Japanese then brushed past three Hurricane squadrons, nos. 60, 258 and 261, which had scrambled a total of 28 aircraft from bases around Chittagong ( only 258 intercepted, losing a Hurricane and claiming a Sally). Now there was nothing between them and Calcutta except the Hurricanes of 67 and 146 squadrons, and the Hurricane flight of 176.

Four Hurricanes led by Flight Lieutenant Derek Brocklehurst had taken off around 1030 as the IJAAF first wave came in, and landed back without loss. 67 and 146 Squadrons, which had scrambled 12 and 9 aircraft respectively, had lost one Hurricane each and had others damaged. The New Zealander pilot F/O Gordon Williams of 67 Squadron shot down one Oscar (his third victory) and claimed another as probable. First Lieutenant Tameyoshi Kuroki, a Japanese ace who finished the war with 16 victories, flew a 33rd Sentai Oscar on this raid and claimed a Hurricane but was himself so severely damaged that he thought of making a suicide dive, though he was eventually able to get back to base.

[The raid had an interesting aftermath for 67 Squadron, which was based at Alipore. On Monday the Calcutta papers were scathing : ‘Where was the RAF? Were they having the day off?’ Incensed by what they saw as unmerited criticism, 67 decided to teach the Calcutta ‘boxwallahs’ a lesson. There was an important race at the Calcutta Race Course next weekend, and as it got underway Hurricanes from 67 proceeded to do a thorough low-level ‘beat up’. The horses scattered, the race finished in the slowest time on record, and carping comments ceased.]

As the Hurricanes of 176 refuelled , there was another raid warning. Four Beaufighters, not cut out for day fighter operations, took off around 1130 and were told to head North out of harm’s way. Five Hurricane 2C(AI)s scrambled ten minutes later. Flight Lieutenant Derek Brocklehurst led in Hurricane HV979 ‘M’, followed by F/Lt. G.R. ‘Bluey’ Halbeard in HW435 ‘N’, P/O A. Whyte in HV710 ‘S’, W/O E.R. Harris in KX359 ‘Q’ and F/O Pring in HV709 ‘L’. Maurice Pring, who was really a Beaufighter pilot and about to go on leave, had pleaded to be allowed to join for a last trip in a Hurricane.

Brocklehurst thought they were going after a lone Dinah coming over for post-raid recce. He was tragically wrong. The Hurricanes were vectored onto the IJNAS raid, and as they dived for the Bettys at 18000′ they were bounced by the Zeroes of the 331st Kokutai, a thousand feet above them and coming out of the sun. Raked by 20mm cannon and 7.7 mm machine guns, Pring, Halbeard and Whyte went down – only the latter managed to bale out, making his way back to the squadron a few days later. Pring’s aircraft was seen to fall in flames with no sign of a chute. Brocklehurst, badly damaged, limped back to Baigachi, but his aircraft was a write-off. Only Harris escaped unscathed. It was bloody shambles once more.

According to Henry Sakaida’s IMPERIAL JAPANESE NAVY ACES 1939-1945 [ Osprey Aircraft of the Aces 22], Warrant Officer Sadaaki Akamatsu of the 331st Kokutai, a very colorful character who finished the war as Lt.(junior grade) with 27 victories, claimed four victories over Calcutta on this day. He was prone to boast of ‘250 victories when sober and 350 when drunk’, but he was also an amazingly skilful pilot who came through the war unscathed, and almost certainly he was in one of the Zeroes that savaged the hapless Hurricanes of 176. W/O Hiroshi Okano, whose final tally was 19 victories, was also serving with 331st Kokutai at this time, but I do not know if he flew in this raid or claimed any victories.

|

|

| Sadaaki Akamatsu | Mitsubishi A6M3 Model22 “Zero” |

The Japanese concentrated their bombing on Calcutta’s Kidderpore docks, causing ‘considerable’ damage. The official communique admitted 500 civilian casualties (one-third killed), and 14 military (1 fatal). Actually about 350 people died. The Japanese lost a fighter and a bomber and claimed 8 destroyed and 2 probables. The British admitted to five losses.

After an air search by Beaufighters of 176 a ground party set out on December 8th to reach the area West of the Hooghly river where Pring and Halbeard were supposed to have gone down. Pring’s burnt-out machine was located in tall grass, and his body found on the 10th. He had been badly burned about the face but had managed to get out of his crashed aircraft and crawl away before he died. No trace was found of Halbeard or his aircraft.

Maurice Pring’s body was brought back to Baigachi, and laid to rest on Sunday, the 12th December, in the Bhowanipore Cemetery. 21 year old Halbeard has no grave : his name appears on column 423 on the Singapore War Memorial located in the Kranji War Cemetery.

By Christmas Eve the Hurricane IIC(AI)s were gone, replaced by Beaufighters. The Hurricane pilots converted to Beaus. In January 1944 the bulk of the Japanese air strength in Burma was transferred elsewhere, making the enemy incapable of posing a serious air threat to Calcutta any longer, though sporadic raiding continued till 24th December 1944.

The city grieved for it’s dead and wounded, among them it’s fallen hero, the 22 year old Englishman it had taken to it’s heart. No one mourned Pring more sincerely than the thousands of children and teenagers who had idolized him. We are privileged to hear three voices out of the past speak of Maurice Pring, and what he meant to them.

“During those many regular air-raids we usually listened to All-India Radio.The reception was not as good as commentary was frequently interrupted by pops,shrieks and whistles caused by atmospherics. Our hero was an Indian Air Force Hurricane pilot by the name of Pring. He was a Squadron Leader who,night after night, shot down Zeroes in fierce combat. We used to listen to his exploits with bated breath; we became an integral part of this man who was up there fighting our battles for us. It was rather like listening to a soccer match in the sky. We reacted to his every valiant move and kill with rapturous joy.

He became the focal point of a Zero attack in the early hours of one morning. As we sat in the flickering glare of a lamp, we stared at one another in utter disbelief – through the static came the unmistakable whining of Pring’s death dive – the end of our friend. There was a silence that seemed to last for an eternity. We all cried unashamedly. The poignant wail of the all-clear broke the unnerving quiet, it’s initial bellows slowly becoming a series of muffled moans.”

? Ron M. Walker, ‘My Wartime Childhood in Calcutta, India’, BBC: WW2 People’s War: Article ID A 2780534 recorded in October 2006

[Copyright Notice : Reproduced under ‘fair dealing’ terms for a Non-commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the original submitter/author ]

Forget the impossibilities and the inaccuracies and listen to the impact Pring had on the mind of a seven year old boy, the way his image as a “Knight of the Sky” imprinted itself indelibly. This is reminiscent of the adulation lavished upon Georges Guynemer of France and Albert Ball of Britain during the First World War. Did the cunning Brits put on some kind of a radio play with Pring as hero? It sounds plausible! And observe the tremendous aura of the Zero – all Japanese aircraft are Zeroes as far as the public is concerned!

Hello again –

I need to know, as well, if there was a RAF billet on or near Kyd Street, and would somebody remember the name of the young airman who brought down three Zeroes (?) in a single night? I believe he was subsequently killed.

Thanks for any help received -”

Sally, 20 March 2007

“I think he was called Squadron Leader Pring, Hurricane pilot for the Indian Air Force in WW2. He would lead the Zero attacks and was killed in one of those attacks. He was the hero of all the kids living in our area.”

Joyce Munro, 20 March 2007

“Thanks very much for that – now that I read it, the name is familiar! Can you recall please, if I am right in thinking that he earned his ‘hero’ status by bringing down three Japanese planes (fighters) in a single night and was the first air raid on Calcutta on 4th December ? I used to have a Statesman photograph of him – now long lost.

Your help is much appreciated.

Sally, 21 March 2007

[These e-mails are from INDIA-BRITISH-RAJ-L archives of March 2007 in Rootsweb.]

[ Copyright notice : Reproduced under ‘fair dealing’ terms for a Non-commercial educational research project. The copyright remains with the e-mail authors.]

Here again we encounter the same inaccuracies – a Squadron Leader in the Indian Air Force flying Hurricanes against Zeroes etc. But let us return to the core of these e-mails : sixty four years after his moment of glory and his death, two old ladies are trying to remember details about the young pilot they idolized as children! One could think of fates worse than that.

Calcutta can truly lay claim to two air aces. One, Flight Lieutenant Indra Lal Roy, DFC (posthumous) flew with the Royal Flying Corps in World War One. Like a meteor, he achieved brief but blazing glory while flying a SE5a with 40 Squadron, scoring 10 victories (2 shared) in only fourteen days before being shot down and killed in 1918, before he had turned twenty. This schoolboy-turned-warrior hero lies buried at Estevelles Communal Cemetery in the Pas-de-Calais of France, far from the city where he was born. He has a road named after him at Calcutta, and in 1998, eighty years after his death, the Indian Post and Telegraphs Department issued a Rs 3.00 stamp bearing his likeness and that of the SE5a.

The other man, Maurice Pring, was not born here, but achieved his renown in the night skies of Calcutta, and met his tragic end in the blaze of noon in the same skies while defending the city. I think that entitles Calcutta to claim him as her own – but she has forgotten him.

I belong to the postwar generation, but I my father told me the story of the Japanese raids, and I remember him saying ‘Sergeant Pring’ when I asked him who shot down the three Japanese bombers in one night. I never forgot that name, and on an afternoon some fifty years after I had first heard it, I walked across the beautiful lawns of the Commonwealth War Graves cemetery at Bhowanipore in Calcutta to stand in silence by the grave of my childhood hero. The sky was azure, and a canna as scarlet as heart’s-blood leaned shyly towards the weathered white headstone, as if it was trying to read the words carved on it :

FLYING OFFICER

A. M. O. PRING, DFM.

PILOT

ROYAL AIR FORCE

5TH DEC 1943 AGE 22

IN LOVING MEMORY

OF OUR DEAR SON

| Pring’s final resting place at the Bhowanipur Cemetary |  |

|

Close up of the Grave Marker of A M O Pring (Courtesy Air Marshal M McMahon) |

[Article Copyright reserved by the author. Photos unless credited individually are from the Author’s Collection]