This is the second part of the recollections of Gp Capt CGI Philip. The first part covers his IAF training, and his first tour of ops with No 8 Squadron on Vultee Vengeances. This part will cover his second tour with the same squadron, flying Spitfires. As before, Gp Capt Philip’s words, we believe, convey a unique sense of those unique times, and we have retained them for much of this article.

View Album No.8 Squadron – Album (1945-46) |

This is the second part of the recollections of Gp Capt CGI Philip. The first part covers his IAF training, and his first tour of ops with No 8 Squadron on Vultee Vengeances. This part will cover his second tour with the same squadron, flying Spitfires. As before, Gp Capt Philip’s words, we believe, convey a unique sense of those unique times, and we have retained them for much of this article.

Left: Airman Johnny Clowsley signals Fg Offr Philip who had just returned from a sortie to shut down his engine. |

In late 1944, No 8 Squadron IAF was in Quetta, having returned from the Burma front earlier that year. They were awaiting re-equipment with a new aircraft type, having discarded the Vultee Vengeances they had flown for their first tour of ops in Burma. There had been a suggestion that they would be converting to the Mosquito, to retain the two-man crew combinations; but in the event Mosquitoes, with their wooden structures, were deemed to be unsuitable for operations amid the heat, humidity and insects of the tropics. So what were they to fly instead?

Spitfire Conversion:

Philip’s eyes still light up at the memory:

“Good news, chaps – we’re getting a lot of Spitfires! Spit VIIIs were coming out. Spit VIIIs were a beautiful aircraft. Like a – later on, when I saw Hunters, I compared the Hunter as a jet-age Spitfire. The handling and the flying – they were comparable. Beautiful aircraft.”

Being selected to fly Spitfires – and being the first IAF squadron so selected – even at this stage of the war, was a genuine honour for the squadron. The Spitfire enjoyed a hugely iconic status, in those days, and its pilots walked a little taller for it.

The squadron went through what seems to have been a very brief conversion to Spitfires. At the time, Philip had never flown even a Hurricane, though he had, as previously mentioned taxied one on one occasion:

“I’ve taxied a Hurricane – belonging to then Squadron Leader Engineer. He commanded the station. Minoo Engineer. Minoo was our 8 Squadron CO also [later]. …

“So anyway, we got onto Spit VIIIs. For Spit VIIIs, it was not the usual pattern like going to Peshawar … for conversion. We happened to be in Bhopal, where we normally go for armament course. So they said, Why not do your conversion in Bhopal, they didn’t have any other course running. So we got our – this is the way of thinking. First, go solo on a Spit V. We had a few Spit Vs in India. And then, after getting a little experience on that, go on to the more advanced Spit VIII. This thinking process carried on for many years. Many of us didn’t agree with it. Like, many of us don’t agree with this <tone of distaste> MiG-21 crashes being attributed to the lack of having a jet trainer, old aircraft, things like that. … Gives the press a lot to say.

“So we did our Spitfire conversion in Bhopal. And from there we went to Ranchi [actually Amarda Road]. Where we formed a fighter squadron, and did our squadron training. And it was nice, because the firing range was off the coast there. We had targets in the sea. We had targets on the beach. And a lot of live firing was done there. … Yes, Amarda Road. … We started off in Bhopal, went to Amarda Road – because from there the firing range was close by, did our squadron training there. … Squadron-Leader Sutherland , Australian pilot. Sutherland was our CO. Yes, in between there was a lot of speculation, as to who would be our CO, we thought we’d get an Indian CO. And finally, when we finished the conversion phase … Prasad dropped in.”

Philip does not conceal his pleasure, at his first CO’s having seen them on conversion to their iconic new type.

Spitfire Ops:

“We again had A Flight and B Flight. A Flight was commanded by a British [officer] – I think it was Dugdale.

“Later on … all COs were British COs. We had Hump, Coombes – Humphreys – Humphreys was a New Zealander. He was our CO by the time we reached Rangoon.

“We had Zahid with us. He was a good friend of mine. He was a Pathan. We’ve flown quite a few sorties together … Zahid and I were Yellow Section. … And he was a regular fighter pilot, so much so that he was posted to a RAF Thunderbolt squadron. When we got Spitfires he was taken off the RAF Thunderbolt squadron and posted – now you go and fly … in your own Air Force. And he came and joined us.”

Sqn Ldr M W Coombes took over command on 10 Jan 1945. “He was the chap who used to have a pet monkey on his shoulder.” The monkey is said to have been named Pilot Officer Cuthbert Prune, for the cartoon character of that name from the RAF magazine Tee Emm. There is a wonderful portrait of P/O Prune on Sqn Ldr Coombes’ shoulder, reproduced in Sqn Ldr Rana Chhina’s The Eagle Strikes – where would we IAF WW2 enthusiasts be without that breathtaking collection?

The same month, No 8 Squadron went back into action, during the Third Arakan campaign. They flew their Spitfires to George strip, 15 miles south of Cox’s Bazaar, late in December and commenced ops on 3 January 1945.[1]

Their immediate task was covering the landings and capture of Akyab. They flew patrols over the island, over the beaches where Allied troops were landing, and over shipping offshore. The Official History says that after the Akyab landings, No 8 Squadron was engaged in offensive reconnaissances against watercraft.

The squadron was visited by a Flight Lieutenant Malik, who was a photographer for the Public Relations cell of the IAF. Malik visited while they were based among paddy fields, in the Arakan. Philip recalls that he had just taxied his Spitfire onto its designated parking slot, and climbed out. His technique, as it happens, was to step onto the sill of the cockpit, and jump straight down to the ground, clear of the wing. Malik watched Philip, then like photographers everywhere, asked him if he would do it again. “What have I done wrong?” Philip asked, “Is this a circus or something?” Amid laughter, Malik told Philip that he was the only person he had seen climbing out of the Spitfire in that manner.

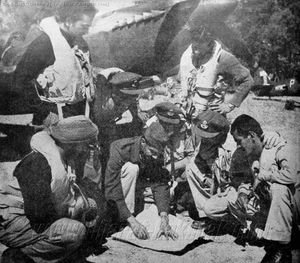

When shown a photograph from the Official History, probably taken around this time, showing half a dozen IAF pilots being briefed in front of a Spitfire. Philip instantly identifies the picture as one that used to hang in the office of Group Captain (later Air Marshal) Rajaram, when he was Director of Personnel in Air Headquarters. With great gusto, he identifies his 8 Squadron mates: his Flight Commander S N Haidar, Abdullah Beg, Clifford Mendoza [2]], and his Pathan friend Zahid .

|

This well publicised photograph shows 8 Squadron pilots during a photo op arranged by Air HQ India. The Flt Cdr Flt Lt S N Haider is shown briefing Beg, Subia, Mendoza, Zahid and Philip.

View Album No.8 Squadron – Album (1945-46) |

Philip’s old squadron-mate from their early Vengeance days, Purnendu Chakrabarty, was killed around this time (CWGC records say on 25 January):

“That was my off day, and I was actually going for a shoot, with some of the boys. The airmen always wanted to come with me. So we take a double-barrel from the armoury and we go out for a shoot. And we’re told not to go too deep into the forest, and don’t get caught with the Japanese, and that sort of thing – don’t go too far.

“And, I was standing just outside the Orderly Room, which is a basha on the slope of a hill. And I saw two aircraft taking off, and – there was the alarm, and these two aircraft had to take off. You get a reconnaissance aircraft, or something, coming in, these chaps had to take off and intercept. So that was the first day that Chuck was leading a sub-section. [The ORB shows that he had led formations of up to 12 aircraft during the Vengeance period.] And – I saw him on the runway, taking off – and – after the take-off, yes, there was – breeze was from the right side. He had drifted off to the left, slightly, and there was a fifteen hundredweight parked on the side. It shouldn’t have been on the shoulder; it was on the shoulder of the [strip] – . And his left undercarriage hit the bars of the 15-cwt. And the aircraft just cartwheeled. I saw him take off; I saw him there; and next thing I knew was the cartwheel. I ran all the way from – must have been about a mile, it’s difficult to – . And that was the end of Chuck.

“[One of the ack-ack gun posts was there] … an anti-aircraft gunner … got to the aircraft – the aircraft hadn’t caught fire or anything; he got to the aircraft – and they were worried about fire. Tugging at him. And someone said, Cut the straps! He didn’t know how to unbuckle the straps. So they cut the straps. They cut the straps, they pulled him out, they didn’t know that the parachute was also hanging onto him. So it’s extra heavy. So one of the chaps said, Look, cut the straps of the parachute. In the meanwhile – there was a lot of struggling on going – and Chuck started vomiting. I think they – they couldn’t have – this all happened during the – it’s difficult to say. Vomiting blood.

“The ack-ack gunners had tears dripping down their cheeks – great lads! English. I told them that it was NOT their fault …

“Basu , who was his gunner … Basu was passing by and he decided to drop in to say hello to Chuck, and to us – knew most of us – those who were on Vengeances. And he was there. So I remember, we put him in a 15-cwt, we took him to Chittagong – we were on George Strip. The Arakan. Went to Chittagong. And his body was being flown – these Liberators, used to come and refuel at Chittagong. They used to do sorties over Ramree Island … And – they’d arranged for his body to be taken to Calcutta. So we went in the 15-cwt, dropped – after that, I don’t remember. In fact, I don’t remember whether they spent the night there, or we came back to – it’s completely blank in my mind; I think Basu and I sat there talking about Chuck.”

The squadron stayed at George for only eight weeks. In late January it covered the assault on Ramree Island, patrolling over the beaches, the harbour at Kyaukput, and over naval vessels on their way to Ramree. Towards the end of February it flew in support of the Kangaw battle, on counter-battery patrols and other tasks. It was withdrawn in the last week of February. This was a somewhat short operational tour, and many in the squadron were not happy about it:

“Then we went to Baigachi, got more pilots, more aircraft. It was all one hell of a mix-up; I think – first tour of ops was ten months. Then second tour of ops was, second tour, third tour, fourth tour, we had that many tours, yes. Each tour was an average of about eight weeks, or six weeks, like that. We just go in there – I think our longest was George Strip.”

Philip laughs again, remembering American fliers in the theatre, flying P-51 Mustangs and P-38 Lightnings:

“Nasty things they used to say, about the Lightnings. Good chaps. Good pilots. You’ll be flying along there; suddenly you’ll find a chap waving his wings there. I remember this particularly … So I waggled my wings, and he’d come close. Formate – and then … I expected him to do this – all he did was salute, and open his throttle and go past; the Mustang could beat a Spitfire. Mind you, I was cruising at – plus four [boost], I don’t know – we could go up to plus twelve [16?], or something like that. Now that chap just opened his throttle and pushed off. We, normally, when we say bye-bye, we – do this. But he just opened his throttle. Impressed me all right!

“And – once, one chap came over our field. I think that was a Lightning. And Zahid was there. This was in Baigachi. Zahid, Subia – these were the chaps we used to pick out, these chaps, to do a dogfight. Camera-gun, they used – and it kept on; that chap wouldn’t give up. Kept on; they were losing height; we said, This is bad. And eventually that chap – hit the ground. In the Lightning.

“We went to Grand Hotel that evening. In Baigachi, we all ended up there. And I – I must say, the chaps were very – we went up to the chaps and said, We’re chaps from so-and-so squadron. Shook hands, Very sorry … That stupid fella, we told him not to get mixed up with you fellas – but he was determined to prove – and you know, we all got chatting, and sat down together. In a way, it contributed a lot, to the pilots getting to know each other, and they sent each other gifts.”

To this day, No 8 Squadron has a reputation for maintaining one of the best unit-level squadron museums, and unbroken records and photographs, going back all the way to the Second World War. Philip is unsurprised. “It was all started thanks to Niranjan Prasad. The Army spirit, which we had in our Indian Army – I’m glad it’s come through, in the squadron.”

Philip served throughout WW2 with the squadron, as did Arthur Berry, Dhillon, Rustom Kalyaniwala, and Mendoza. In addition, Deviah Subia rejoined the squadron at one of the strips in Burma .

Back to Rangoon … :

As the war wound down, and the Japanese fell back, the city of Rangoon was retaken by 26th Indian Division on 3 May 1945. This was a potent symbol of Allied resurgence, helping to wipe out painful Allied memories of humiliating withdrawals in early 1942.

No 8 Squadron (now commanded by Sqn Ldr J S “Tuss” Humphreys) moved to Mingaladon airfield, just outside Rangoon, on 26 July 1945. They went by the troopship HM T/S Devonshire, embarking at Princip Ghat on the River Hooghly.

By the account of the squadron ORB (which goes into particularly vivid detail over these few days, including a description of the shattered state of the docks at Rangoon) the trip from Baigachi to Mingaladon was somewhat disorganized. The squadron was hurried aboard the troopship, which then waited three days before weighing anchor. There were inadequate arrangements for food for the Indian ORs while they waited, and they had been made to give up their K-rations before boarding. There were no arrangements for accommodation on arrival in Mingaladon – “everyone slept on wooden floors on newspaper”.

|

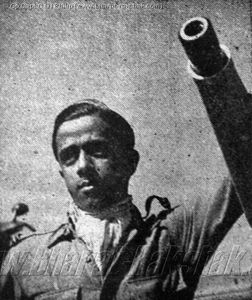

This photograph of Philip by his Spitfire was one in a series of ‘Portraits’ published in the RIAF Journal.

View Album: No.8 Squadron – Portraits (1945) |

Nevertheless the squadron made their soldierly best of it. The officers contributed from their own pockets to a fund to keep the IORs entertained aboard ship (Fg Off Katrak being mentioned by name for a contribution of Rs 100/-, which was a particularly munificent sum in those days), and personnel of 906 Wing at Mingaladon gave them dinner, with drinks on the house for the entire squadron on the night of their arrival. The squadron was in action five days later.

Soon after the squadron moved to Mingaladon, the swashbuckling Flight Lieutenant Ranjan Dutt joined them. Dutt was a larger-than-life figure, even among the many flamboyant IAF pilots of the time. He was one of the first batch of 24 Indian VR officers who had trained in the UK, and had served operationally with RAF squadrons in Europe and the Western Desert. He had completed a prestigious Fighter Leader course in the UK, just before joining No 8 Squadron. Philip says that it was Dutt who initiated the squadron into using the now-universal Finger Four tactical formation – until then they had been flying in pre-War three-aircraft vics.

Philip recalls Dutt:

” … Great chap, with a party – and he was always ready to pick a fight. … Ranjan would find some excuse to – we’d be walking down the corridor, [someone would brush past]. He’d turn around and say, Mind where you’re going, can’t you see I have two glasses in my hand? He’d say, One minute, put the glasses down and punch the chap. And before you knew it, there was a fight. … You go to Princes, in Grand Hotel in Calcutta; you walk in there; and you suddenly find a chap – sliding down the floor. ‘What the hell’s happened?’ ‘There’s a fight going on, there.’ ‘Come along, let’s not miss it!’ And the chaps would go inside. And Ranjan was the kind of chap who’d go in there for the fight. Anything. It was either the British and the Irish, or the Scottish and the British, or the Indians and the British – there’s no end to it. These Americans used to come there, and say, ‘I can’t take it. We give up.’ “

… and visiting Moulmein:

Once the squadron had moved to Mingaladon, Philip was keen to visit Moulmein, just across the Gulf of Martaban, and check on his family. His CO allowed him to take the Harvard, from Mingaladon to Moulmein, once Moulmein had also been secured.

“I got a Harvard; … Alan Chaves was to fly with me, drop me there, and bring the aircraft back to the squadron. And Ranjan Dutt and Abdullah Beg, they said, Phil’s going, we’ll give him an escort – just a nice excuse, to come on a sortie – We’ll give him fighter cover. So two Spitfires took off, after me; re-joined me as I was reaching – “

In addition, Mendoza and Kalyaniwala came in a Dakota with some Gurkha troops. It must have been an emotional return for Philip in particular, who had gone to school in Rangoon and Moulmein, and thought of Moulmein as home.

“We landed there, there was a Japanese colonel, who was there in his car. And all these Japanese soldiers – when they went past the aircraft, they would have to salute. Very disciplined lot of chaps. And this colonel, was about six feet tall. Tall, for a Japanese. Smart chap. He had his car there … I said, I want to see my folks. ‘Your folks here? Right through the war?’ I said, Yes. ‘Were they looked after all right?’ I said, Yes, they were looked after. One chap even came and gave my mother some money; This is rent, for that house they were living in.” [The family had moved out of their own house, which was requisitioned for a period by the Japanese occupiers, and lived on a farm belonging to a neighbour, a retired civil servant.]

Ranjan Dutt and Abdullah Beg (and possibly Abbas Hussain) were with Philip, and they suggested going immediately to Philip’s old house to look for his mother. They accosted the Japanese colonel and informed him they were requisitioning his car. Philip recalls, “I said something about Lord Louis Mountbatten; I said, Lord Louis Mountbatten will take care of it.” The colonel began to take his effects, including his ceremonial sword, out of the car. Ranjan Dutt, with the adrenalin of victory coursing through his veins, wrested the colonel’s sword from him.

There was one Japanese officer in Moulmein superior in rank to the colonel, but he was in sickbay. Dutt proposed, Let’s go and say hello to him. So the small group of Indian officers trooped in to see the defeated Japanese senior officer, stood around his cot – and appropriated his sword as well. Along the way they collected several other swords. They spotted an officer on a bicycle with a sword:

“We said, Aha! He’s only on a bicycle, but he’s got a sword! We were in a car. I think the chaps must have recognised the colonel’s car. And – we’d take that sword. Mind you, there were four, five of us there – we had our service pistols with us. But they had their whole battalion there. And if they were not disciplined people, they could have wiped us out of there, and nobody would have known the difference. Very disciplined.

“I earmarked one sword for our intelligence officer, – and one sword for the squadron – and one sword for myself, and Ranjan, and all of us had one sword each. That’s the story of the sword.”

Philip did manage to locate his mother, and the rest of his family. His mother, four sisters and two younger brothers, had all remained in Moulmein throughout the War, and through the Japanese occupation, though not actually in their own house. Neighbours had taken the family to an alternate location across the river, which was considered safer.

He wrote afterwards:

“It was indeed ‘A Full Circle’ … “

… a sentiment that was shared by much of Fourteenth Army, as they re-occupied the towns the British had been forced out of, back in 1942.

But in retrospect, Philip is not proud of his part in seizing the swords, that heady day in Moulmein. When you come down to it, Philip and this small group of Indian officers in Moulmein were far from being the only Allied personnel taking possession of Japanese swords at this time. All over Burma, South-East Asia, and the Pacific theatre, young Allied military personnel were coming into physical contact for the first time with Japanese personnel, and legitimately requisitioning military equipment and goods. In many of these encounters, documented in almost every Allied memoir of the time, somebody appropriated their erstwhile adversaries’ swords. This behaviour is understandable, and far from the worst that victors have sometimes indulged in, at the moment of victory after several years of war. But Philip’s patent decency and fair-mindedness have given him some trouble since then:

“As I grew older, reading about the samurai, and the family traditions, and things like that, I felt very guilty about it. I said I should try and trace this family here, and give this sword back to them. I felt I’d done a very wrong thing. And I wanted to make up for it.

“But the years kept going on, and – that colonel couldn’t have been more than three years older than me, two or three. I said, even then, I’m 82 now, he must be 85 plus. Mind you, he was such a fit chap, I’m sure he’s alive, and if he’s alive somewhere, I want to give it.”

During the confused travel following Partition, No 8 Squadron’s sword came close to being stolen, on a Calcutta railway platform. An Air Force sergeant who knew Philip saw somebody walking nonchalantly away with the sword, challenged him, and retrieved it. He returned it through Philip’s brother, who by that time was also in the Air Force. Philip gave it to a cousin of his wife, who wrote a book on the swords of Indian maharajas. It is now part of the cousin’s collection.

Philip did organize the return of one sword, which had been retained by one of the individual officers, to the squadron many years later. The aging officer was happy to return it, and the sword went back to the squadron with his blessings. The squadron wrote to Philip in appreciation.

Gp Capt Philip still has one sword from that day. Though the leather of the scabbard is becoming brittle, and the sword no longer shines as it used to, he still nurtures hopes of returning the sword to its original owner one day.

|

Gp Capt Philip bought out his war trophy – a Samurai Sword that once belonged to a Colonel of the Japanese Army. |

| A close up of the inscription on the Sword. |  |

Less than two weeks after the squadron flew into Rangoon, the first atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. At the time Philip was returning by ship, from leave in Kerala. He wrote later:

“It was amusing to hear the ship’s officers talking about the consequences of the explosion – huge waves, etc. Got us worried.”

Japan surrendered on 14 August, and operations were suspended.

Surrender Ceremony:

Rangoon, where Philip and his squadron were now based, was the location where the first surrender agreement [Footnote: The Japanese signed three major surrender agreements: this one in Rangoon in August; at Tokyo Bay aboard a US battleship on 2 September; and at Singapore on 12 September] was to be signed. Signing for Japan would be Lieutenant-General Takazo Numata , Chief of Staff to Field Marshal Count Aisarchi Terauchi, Supreme Commander of Imperial Japanese Forces, Southern Region. According to some accounts, the signatory for the Allies was Lieutenant-General Frederick “Boy” Browning (previously GOC of I Airborne Corps at Arnhem – and incidentally, husband of the novelist Daphne du Maurier), Chief of Staff to Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander, South-East Asia Command.[3]

The Japanese delegation, headed by Lt-Gen Numata, came to Rangoon on 26 August. They flew in in two Mitsubishi Ki-57 (Allied code name “Topsy”) Japanese transport aircraft painted white, escorted by relays of Allied fighters. For the last leg, from Elephant Point to Mingaladon, the escort included Spitfires of No 8 Squadron. Philip recalls:

” … We provided the escort – for their General signing the surrender – coming in. … On that day … we had to go in to the Jubilee Hall …

“The first day, they had to call it off. Because of weather. Or the Japanese didn’t rendezvous at the given time. … I was [flying escort] on the first one. And we had to call it off. And the second day, everybody was lined up, and the second day I was lined up where they would come down. We had our chaps lining-up the entire runway. Just a security precaution; we didn’t want some chap to go there and take vengeance. And we had our – we were in usual uniform, with our pistols. [4] We were – after the gangplank, we were there. And they got into the car, and … [drove off] to Jubilee Hall.”

Ominously for Philip’s later peace of mind, Lt-Gen Numata’s first words at the surrender ceremony were to thank the Allied commanders for their courtesy in allowing the Japanese officers to wear their swords. Lt-Gen Numata’s speech is mentioned in Richard Storry’s book, Britain and Japan at War. Again, there are some fine photographs (and one interesting charcoal sketch) of this historic occasion in The Eagle Strikes.

No 8 Squadron would also provide escort to the aircraft of Japanese envoys later in mid September, when they came for other ratification meetings.

Post Surrender Ops:

It is one of the unremembered features of the Burma front that operations in some form, and even some sporadic fighting, continued for a long period after the Japanese surrender. No 8 Squadron remained on ops till November 1945, and returned to India only in January 1946.

After the surrender, No 8 Squadron took on many different types of operations. There was some residual shooting required, but many other types of missions were also carried out. Among them were leaflet dropping (which the ORB refers to as “Nickle bombing”) to scattered Imperial Japanese Army units, informing them of the surrender; observing Japanese movements, vehicle and boat concentrations; and, interestingly, dropping money to Force 136 for their final pay-up. Philip recalls a conversation with a colleague during this period:

“I met him in the tent; we had a tent there. And, in those tents, we had this – drop tanks. With silver rupees in it. So, as I walked into this tent: ‘Sir, kick that tank. Kick that tank.’ So I said, ‘Why?’ ‘So you can say that you kicked – a million bucks!’ There were silver rupees in those, and we had to drop them – they would carry those overload tanks. And, we had to drop it, over places around Moulmein. Where Force 136, and the V Force were operating.”

The squadron ORB records some of these operations with relish: “This morning we find F/O KALYANIWALA a very unhappy man. He was mortified because he feels he has squandered one lack [sic] and 40 thousand rupees on the countryside of Burma in the space of 5 minutes. No wonder he is unhappy.” Referring to an abortive operation of the same type, it adds, deadpan: “Owing to bad weather the Mission proved abortive and the containers were brought back to the mess and deposited under the Adjutant’s bed. Our Adj had a sleepless night.”

The squadron participated in a major flypast over Rangoon harbour in October 1945, to welcome back Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, the pre-War British Governor of Burma. The ORB records, “The formation was exceptionally good, and we received a ‘Strawberry’ from Air Marshal SAUNDERS, AOC Air Headquarters Burma”.

Philip continues:

“When we were in Rangoon after the war ended … Ranjan Dutt … was ready to try anything out. And when we discussed this [blinding on night-flying because of flares from the exhaust] – Simple – all you got to do is, keep the throttle slightly open and control your speed – the whole speed, the attitude of the aircraft would change – but there would be no blinding of the exhaust from the stubs of the engine.

“We actually did night-flying there – in fact, it was quite an impromptu affair; the RAF chaps – we had an RAF squadron also on the – and they were commenting on it. I think six aircraft got airborne, just to fly around. The CO called up and said to join up. Rendezvous point was over the airfield – goose-neck flares were on, so there was an easy rendezvous. Height was given – rendezvoused there. And we went on to say, this is the IAF! So – we formed a I, then a A, then a F – separately. Came back and landed, and everybody was very happy. And of course the chaps, all the other pilots in the region including the Burmese Air Force … they were all talking about it.”

“And Bala Manivelu … Mustn’t forget Bala Manivelu. He’s from Madras. And Bala … – wonderful chap. He could tell a joke … to a group of ladies – and the ladies will laugh and enjoy it. And somebody else … tells the same joke – they all turn around and say, What horrible this thing, … – Bala could tell a [smutty] joke and get away with it. He had a way with him.”

Bala Manivelu and Johnny Bouche were two of the small number of the 17th course, who trained in Canada and returned to India in late 1945 to join 8 Squadron. However, Manivelu did squeeze in some wartime sorties in Europe on the way back, Philip believes on Tempests. “Those days it was easy, I mean, if you were keen to fly, there were half a dozen guys ready to help you with it.” Manivelu made friends, and cadged some rhubarb type sorties over France. He qualified thereby for the Air Crew Europe campaign medal, which Ranjan Dutt and Harry Dewan also wore.

“Ranjan … did a Fighter Leader course in England. … Then he was in Cairo – he flew there and he got the Middle East medal – Africa Star. … Qualified for that.”

No 8 Squadron’s time in Mingaladon was not without loss. Flying conditions were difficult, and the monsoon was still active. In August 1945, Philip’s friend Zahid went missing, after taking off for a supply-dropping sortie in atrocious weather. Four aircraft mounted a search for him, but he was never found. In addition:

“We had a casualty over the Bay. Near Moulmein. … This pilot, Snell – he crashed, and all they found was a scalp of his, floating on the – … He was flying Number Two there – and normally when you’ve got a Number Two there, your leader is supposed to turn left – so that he’s closest to the water. And No 2 is – safer. And he’s OK, because he’s watching the ground the whole time. So that was the British Flight Commander, and this boy was – and Coombes had his – he said, Should we have a funeral, or shall we have – What funeral? He had a matchbox – a cigarette box. And this scalp was in that. That was all we found when we … Indian. A youngster – a young Pilot Officer, who was posted to us … an Anglo-Indian boy. Played football – I wanted him for our squadron team – centre half – we needed one. We were to play that evening – we lost him. Sad.”

But there were happier moments too. The squadron’s ALO, Captain Ormroyd, married Elizabeth, an attractive blonde nurse with Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Nursing Service, while they were all stationed in Rangoon. The squadron was determined to give a suitable present, but there was not much time left; it would have to be procured from Calcutta (Rangoon was still in a state of post-War devastation); there were holidays coming up; and it would have to be organized on a weekday, when the shops would be open. Philip, who knew Calcutta well (“You know people there, you can go through the back door, and get in”), was eventually detailed to fly a Harvard from Rangoon to Calcutta, to organize the wedding gift. In addition the CO wanted suitable mementoes to present to two senior NCOs who were leaving the squadron:

“In addition, I had to buy two tankards, one each for Titch Mazumdar, Flight Sergeant of A Flight, and Parde, who was Flight Sergeant in B Flight [my flight]. So I had to get a present for them also.

“I went there, I did the usual things, I was getting late – I wanted to be in time for the [wedding ceremony in] Church. And winds were against me; if I’d done the usual, Rangoon-Akyab, refuel … [it would have been] two sides of a triangle. I’ll go straight to Rangoon. If things go bad, I can always make it; the shore is close by.”

Philip pushed his aircraft to the limits of its range, to fly straight from Calcutta to Rangoon without the refueling stop that was usually made in Akyab. He missed the wedding ceremony by five minutes, but flew over the church on his way in. “I made it. A show over Church. He’s back!” He was told afterwards that the CO, already seated in church, pointed skywards at the sound of his engine, and gave a thumbs up.

Years later Flt Sgt Parde, who had gone on to work for Air India, presented Philip with a tankard in return:

“I said, Not the same tankard! ‘No Sir, that tankard I’ve got; I won’t give it to anybody.’ But he presented me a nice silver tankard with a glass bottom.”

Return to India:

In January 1946, No 8 Squadron finally returned to India, crossing most of the sub-continent, in a lengthy and complicated move from Rangoon back to its official birthplace, Trichinopoly. Freddy Scudder, Livy Mathur, and Navroz Lalkaka, all gifted musicians besides their other attributes, were all posted to 8 Squadron at this time, enlivening social occasions with their music. Philip recalls Scudder in particular as a talented guitarist.

At this time, No 4 Squadron of the RIAF had been designated to go to Japan with the British Commonwealth Occupation Force, operating Spitfire XIVs. However, No 4 Squadron had only just converted to Spitfires. No 8 Squadron, as the most experienced RIAF Spitfire unit, provided some of the pilots. Transfers included Flight Lieutenant RS “Shippy” Shipurkar, who became one of 4 Squadron’s Flight Commanders for their sojourn in Japan. In addition, No 8’s senior pilots helped develop a procedure for operating the Spitfires on a one-off basis from aircraft carriers, when it seemed possible that they might have to take off from a carrier on reaching Japan. The procedure involved placing a wooden wedge in the wing, to hold the flaps at a non-standard angle, 12 degrees, that seemed appropriate for the unusual operation:

“So you got a wedge of 12 degrees – put it in the wings [before raising the flaps, to hold it in place at that unusual angle. It falls out when the flaps are lowered] – and we tried, I tried it out. Myself, Abdullah Beg. … That gave you an extra lift on the wing. And we tried it on the runway, and we said [if we can] take off in so much distance – with the carrier movement, and into wind, we could take off from the carrier. Landing was [with] full flaps … minimum speed with power, and … chop our engine, and stop there. And yes, I think they were going to use arrester nets at the end. In case you needed it.

“Pilots from 8 Squadron went. I might have been on it. But I was selected for instructors’ course, and we went to England. And I had to fly to Delhi, for the interview for selection for the instructors’ course.”

That year, 1946, Philip was one of first batch of Indian instructor candidates selected to go to the Central Flying School, the premiere flying training establishment of the RAF, at Little Rissington in the UK.

“We had to have 750 hours’ total flying, or something like that; which I had, and … ” Philip grins as he names a few senior officers who hadn’t managed to accumulate that much flying time in several years including the war.

In April as the time drew near for Philip to finally leave 8 Squadron, the CO, Squadron Leader Minoo Engineer, organized a farewell dinner for him in the mess. In an echo of Philip’s own shopping expedition at the time of their ALO’s wedding in Rangoon, Freddy Scudder, who knew Madras well, was detailed to fly the squadron Harvard to Madras and procure a silver tankard inscribed with Philip’s name, as a farewell gift. It was expensive for the time: “I think he paid nine rupees. There was a big speech by the Station Commander, and all that.”

Philip’s happy memories of No 8 Squadron remains as strong as ever, and he still has that tankard.

Notes:

[1] They had joined 221 Group RAF, the AOC of which was AVM Cecil Bouchier, who as a Flight Lieutenant back in 1933 had been the first CO of No 1 Squadron, IAF.

[2] Who was to crash in a Dakota in Kashmir in 1947, and whose body was found 33 years later

[3] Some accounts say it was Lieutenant-General Sir Montagu Stopford, GOC 12th Army.

[4] The squadron ORB says, “10 aircrew of our squadron could be seen standing on the strip with sten guns”

Recommended Links

The Supermarine Spitfire – Polly Singh

List of Commanding Officers of 8 Squadron