by Tenzin C. Tashi, Sr Researcher, English Academic Section, NIT.

On a small hillock within the precincts of the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology at Deorali, Gangtok, there is a Chorten that few know about. Mostly forgotten and neglected, it is only recently that a plaque has been erected memorializing it as the Chorten containing the mortal remains of Crown Prince Paljor Namgyal of Sikkim and a stairway built to encourage visitors, both locals and tourists alike, to visit and immerse themselves in a quiet, unheralded part of our Sikkimese history.

On a small hillock within the precincts of the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology at Deorali, Gangtok, there is a Chorten that few know about. Mostly forgotten and neglected, it is only recently that a plaque has been erected memorializing it as the Chorten containing the mortal remains of Crown Prince Paljor Namgyal of Sikkim and a stairway built to encourage visitors, both locals and tourists alike, to visit and immerse themselves in a quiet, unheralded part of our Sikkimese history.

Other Chortens of the royal family members exist at the Lukshyama royal crematorium on the hills high above Gangtok. Only this Chorten has been sited differently. No formal documentation in this regard has been traced, but old-timers say that some Rinpoche decreed that the Chorten should be built at this spot. Now, no one can even remember which Rinpoche it could have been.

On October 1,1958, the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology was established by Royal Charter granted by our Founder Patron, Chogyal Tashi Namgyal with 19.96 acres of land gifted in perpetuity to the Institute. However, the Chorten was kept out of the purview of the gift.

‘First, the small Chorten (indicated by Figure 1) commemorating Our late lamented and dearly beloved MaharajKumar Paljor Namgyal will be exempt from this gift. Proprietorship and maintenance of this Chorten will continue to vest in the present authorities.’ (Annexure II, Charter of Incorporation, 1958)

The Prince

Kunzang Choley Namgyal aka Paljor Namgyal was the first-born and eldest son of Their Highnesses Mahajara Tashi Namgyal and Maharani Kunzang Dechhen Tshomo Namgyal. He was born on November 26, 1921 and was commissioned on November 30, 1940 in the Royal Indian Air Force (later IAF). Pilot Officer Namgyal died in service on December 20, 1941, at only 20 years.

As a people, we Sikkimese have a remarkably insular outlook towards events and entities. We like to parrot a few bits of information off of Google, but we don’t really like to trawl deeper.

And, of course, there were the usual conspiracy theories flying thick and fast. We heard of how the British purposely provided the Crown Prince, a brilliantly charismatic leader who attracted people in droves and with an independent mind, with a plane with a leaking fuselage to inevitably crash. Prince Paljor Namgyal’s epitaph would forever remain just a Pilot Officer who died in active service in WW2 in a plane crash if we didn’t ask questions, do the research, and uncover documented facts.

I was always fascinated by his life story. A young oriental Crown Prince from a landlocked Himalayan kingdom joined the IAFVR (Indian Air Force Volunteer Reserve) during WW2, the first and only aviator in the family. And then that all too fatal accident that claimed his life and left his parents and the kingdom bereft of a Crown Prince.

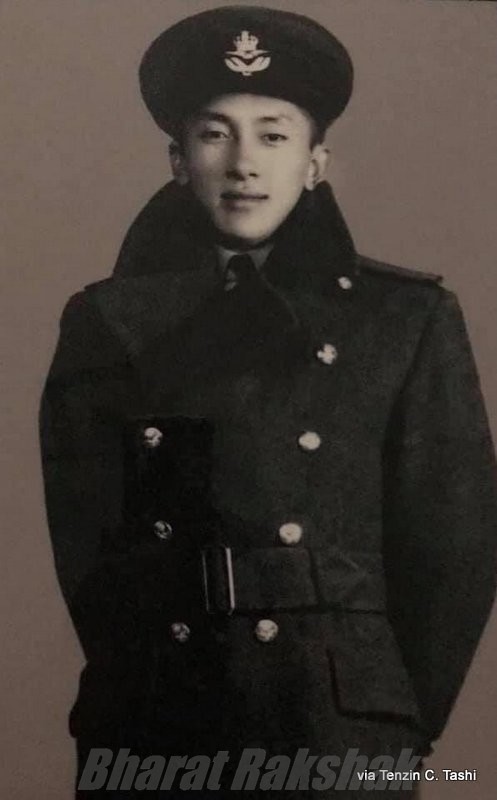

We had, like many other homes in Sikkim, a sepia photo of him in his Pilot Officer uniform. There were other pictures too of his flying days and his visits to his mother at Taktse Palace. There was a green clock at home; it never told the time. But when I asked, I was told it belonged to the late Crown Prince. There were hand-painted glass plates too showing airplanes, dirigibles, and other flying machines. Yet his actual flying journey was shrouded in mystery, and I simply had too many unanswered questions. It didn’t help that a local writer made tall claims in a newspaper that the Crown Prince perished in the jungles of Burma, and his grandfather went to receive his body. If only it were that easy to alter history.

When I wrote Pilot Prince, the Crown Prince’s profile on my Scribd page in the hope that someone from his flying days or a war historian would stumble upon it and provide more information, Jagan Pillarisetti reached out to me:

“I am an amateur aviation historian who has done much research on the Indian Air Force on WW2. I recently read your write up on Crown Prince Paljor Namgyal on Scribd. I learnt everything that I was looking for and would like to commend you for the article that filled a major gap in my quest for information. I have had an interest in him as I have been researching the Squadron he served in for many years. I was most intrigued by your reference to photos of him in uniform. Would it be possible for you to show or share these photographs of him in IAF Uniform or training?”

Jagan and I started corresponding around 2011- I shared photographs, and he generously shared his research findings with me. Initially, there was some kind of confusion because one version of the crash incident suggested that Paljor Namgyal was in the rear cockpit and his coursemate, C. Dhairyam was the pilot.

“Dhairyam who was piloting with P/O Namgyal, the Heir Apparent of Sikkim, in the rear cockpit, undershot very narrowly and his tail wheel hit a small mound at the beginning of the runway and crashed. The Prince was killed and Dhairyam became a cripple for life.”

The Sky was the Limit,1997: 32

How exactly did P/O Namgyal become a pilot anyway? It was Sir Basil J. Gould, British Political Officer of Sikkim, Bhutan and Tibet who encouraged Maharaja Tashi Namgyal to send his eldest son for pilot training to aid the Allied war effort during WW2. He took a keen personal interest in the prince’s training; the fact that the official correspondence about Paljor Namgyal’s progress is addressed to the PO rather than the Maharaja of Sikkim avers to Gould’s primacy in this matter. It also explained why I could not find this information in the Palace Archive despite many cramped hours on a small stool in the basement of Tenzing & Tenzing, where the lone naked incandescent bulb would routinely go out, and I would perforce rely on my mobile torchlight to scour the dusty files for the elusive missing source material.

In an interesting development, the ORB (Operations Record Book) of No 1 Service Flying Training School, Ambala became available, and it was firmly established that P/O (Pilot Officer) Paljor Namgyal himself was piloting the plane that fateful December day of 1941. The ORB threw up an immense wealth of information that made it possible to piece together the path that P/O Namgyal undertook during his initial days in the Indian Air Force.

It becomes important first to briefly understand the working of the Indian Air Force in 1939-41. At the beginning of the Second World War, it was decided to have a IAF Volunteer Reserve. Pilots and observers were inducted in ‘Batches’ or ‘Courses.’ Every Course /Batch of pilots had a varying number of pupils who would undergo training at different levels before they were sent to Squadrons. P/O Namgyal belonged to the 5th Course.

“Initial training was of six weeks duration with classes in ground subjects, physical training and drill. Up to the seventh course, all entries were straightaway commissioned as Pilot Officers in the Indian Air Force Volunteer Reserve. From the eighth course onwards the entry was as cadets and after Elementary Flying Training School training, they were commissioned as Acting Pilot Officers.”

(The Sky was the Limit,1997: 22)

The 5th Pilots Course.

The 5th Pilots Course batch commenced training at the Initial Training Wing at Lahore in November 1940. The recruits were commissioned as Pilot Officers on the date they reported to duty – November 30 ,1940. Other stalwarts from that batch included Air Chief Marshal H. S. Moolgavkar (later based in Pune) and Air Chief Marshal O.P. Mehra (later based in Delhi). The training at ITW was usually non- flying related such as parades, drills, weapons drills, physical training and games,etc.

To Ambala

After four months of the basic training, the batch was sent to Ambala in March 1941 to the No.1 Flying Training School (later Service Flying Training School). The Ambala FTS conducted training in two stages: Pupils had to first pass the ITS (Initial Training School) and then complete the ATS (Advanced Training School).

The Batch consisted of 30 Officers and 7 NCOs who started training as pilots. 9 Pilots belonged to the Burma Volunteer Air Force, and the rest were Indian Air Force Volunteer Reserve. This is confirmed by the VR badges worn by Pilot Officer Namgyal in his photographs.

The 5th Pilots Course at Ambala started on March 3, 1941. As required, they underwent training at the Initial Training School and completed it on May 24, 1941. During this time, the Pilots learnt the basics of flying in Tiger Moth aircraft, a 1930’s British biplane operated by the RAF as a primary trainer aircraft.

Plt Offr Namgyal during his training days – most likely taken at ITS Lahore or at the FTS Ambala.

Namgyal is standing next to ASJ Henry (aka Henry Sathyanathan)

Namgyal with Hirendra Nath Chatterjee, who would later retire as an Air Marshal. Chatterjee was from the 4th Pilots Course.

After completing the Initial Training School, on May 26, 1941, the Pilots started the Advanced Training School. ATS included flying training on larger and more capable aircraft like the Hawker Audax (tropicalised version for RAF use in India), Hawker Hart (a two-seater biplane light bomber aircraft) and Westland Wapiti (a British two-seat general-purpose military single-engined biplane).

Training Trip to Drigh Road, Karachi

On August 4, 1941, B Flight of the Course went to Karachi to Drigh Road for ATC and Navigation Training. This included Pilot Officer Namgyal.

Operational Order confirms that the following were in this detachment:

P/O Lala (Air Party), P/O K H Motishaw (Air Party).

By Train from Karachi to Ambala

1st – Rail Party: P/Os Khin, Tun, Yain (all Burma VAF), Namgyal, Dhairyam, Haig, Daniel, Misra, Gage, D. A. Shah, Chatterjee, and Sgt Harvey.

On August 17, 1941, B Flight returned from Karachi after completion of the training.

Tactical Training at Jullunder

Five days later, on August 22, 1941, 5th Pilots Course started Tactical Training for the first time. Flight from ATS was sent to Jullunder for exercises in dive and low-level bombing, interceptions, recce, and offensive patrols. Ground Defence Drills were also carried out.

Sent by Train: P/O Rahman, Maung Hla Yi (Burma), Varma, Daniel, Murat Singh, Agarwala, Bukshi.

By aircraft (the Air Party) – P/Os G S Singh, Dhairyam, Namgyal, R. Singh, Clift.

Operational Order shows that P/O Namgyal flew a Tiger Moth Aircraft with Aircraftsman Goodfellow as his passenger for the cross-country flight to Jullunder. The aircraft flew to Jullunder on August 23, 1941, starting at 11 a.m. and reaching there by 12 noon.

On September 4, 1941, two members of Namgyal’s course – Sgt Harvey and Pilot Officer Cherala Raghava Rao- were killed in the first fatal accident at the school. The aircraft crashed fatally injuring both the occupants just days before the completion on September 13, 1941, of the tactical training of the 5th Pilots Course.

Concerns about his training

A fortuitous lead from a retired Brigadier to a declassified secret file of the ‘X’ Branch of the External Affairs Department, Government of India in the National Archives of India turned up the missing piece of the jigsaw.

It was a correspondence file with the subject: “Progress Report of Maharaj Kumar Paljor Namgyal, eldest son of the Maharaja of Sikkim who is undergoing training in the Air Force. Report of his death in an air accident in Peshawar.”

The file wasn’t exactly a glowing paean to the progress of the Crown Prince; the flurry of correspondence between BJ Gould, Political Officer, Sikkim with Wing Commander Roger Mead, Head of the No 1 Flying Training School, Ambala and H. Weightman, Deputy Secretary of the Government of India in the External Affairs Department, Simla outlines Mead’s concern about ‘young Namgyal’; he had ‘a 10 horse power car and a motorcycle’ which was taking up ‘quite a lot of his time’ resulting in him becoming ‘rather disinterested and lazy’ toward the end of training.

Mead was determined to make Namgyal ‘a useful officer’ and requested the PO to mobilise the Maharaja of Sikkim’s influence to ensure his son completed the course with better focus and was accepted for active service.

Gould, however, requested that Group Captain Bussell who knew the Sikkim royal family go to Ambala and give Paljor Namgyal a good lecture. This ‘stiff talking to’ had the desired effect, and the Prince’s progress thenceforth was a ‘vast improvement.’ He went on to successfully complete the training course and enter active service, proving Gould’s asseveration that ‘admittedly also he is a boy of considerable parts.’ (File No 200-X/41 (Secret) held at the National Archives of India, 1941)

It helps to bear in mind that flying training in those rudimentary years of the RIAF was no easy task by any yardstick. Young men were tested very strictly before they were accepted into the Initial Training Wing at Lahore. Even then, about 30 per cent of the new recruits would, in the course of being whipped into shape as useful pilots, fail the Initial Training School, and a further percentage would fail out of the No. 1 Flying Training School at Ambala.

“There was no radio in any aircraft used for training. Navigation was done with compass and maps. The points of starting and the destination were joined by a line. On either side of the line from the starting point there were two five degree lines drawn on either side. The pilot flew dead on compass course and after a fixed time of five minutes checked up on the ground what the position was. The deviation was corrected at the half way point, all the while checking the land marks on the way, particularly roads, railway lines, rivers and canals, which some didn’t, with disastrous conse- quences” (The Sky was the Limit, 1997: 28)

The Sky was the Limit, 1997: 21

“There was no proper training institute as such. It goes to the credit of the pilots of the early days who belonged to the first five courses recruited after the declaration of the Second World War, that they came up to the highest standard required by any group of pilots from any country who fought in the war. After independence they rose to the highest ranks of independent India’s Air Force and successfully conducted India’s wars. Considering the halting and hesitant way the British developed the Air Force, the achievement of the pilots and airmen, who started off with ad hoc training and antediluvian aircraft, was remarkable.”

Passing Out

On September 21, 1941, the 5th Pilots Course completed their training with the ATS and “Passed out”. On this day, Pilot Officer Namgyal would have got his “Wings” badge. The pilots were then posted to regular Squadrons for Operationalisation.

Pilot Officer Namgyal is shown on the strength of No.1 Squadron IAF on September 29, 1941. He seems to have been posted to the No. 1 Squadron along with his coursemate, C A Dhairyam.

P/O Namgyal of No 1 Squadron, RIAF was among the first to train on and fly the Lysander II in India. Critically, he would be the first fatality in the ‘Lizzie’ as the Lysander was affectionately called.

India remained the haven for biplanes till August 1941, when the first batch of 48 Lysander IIs arrived at Aircraft Depot, Drigh Road. These were allotted to Nos.28 Squadron RAF and No.1 Squadron IAF. Subsequently, No.20 Squadron, RAF, Nos. 2 and 4 Squadrons IAF were also re-equipped with the Lysanders.

The first Indian Squadron earmarked for conversion to the Lysander was No.1 Squadron. At that time the Indian Air Force consisted of only two Squadrons, No.2 having been raised a few months before.

The Squadron was presented with their official “Tigers” badge on 13th Oct 1941, by the Governor of NWFP, Sir George Cunningham. On 7th November 1941, another official ceremony was organised where this time, the Governor of Bombay, Sir Roger Lumley officially handed over thirteen Lysanders to No.1 Squadron. The aircraft were paid for with donations from the Bombay War Gifts fund.

The Squadron suffered its first casualty on the Lysander on 20th December 1941, when Pilot Officer Paljor Namgyal , who at that time was the crown prince of the Kingdom of Sikkim, undershot trying to land at Peshawar. The aircraft R1989 hit a bund and overturned – killing the pilot and seriously wounding the observer. (Pilarisetti, 2017)

The Service record for P/O Namgyal in the IAF database on the Bharat-Rakshak website shows that he was the pilot of Lysander II tail no R1989 and his observer was P/O R.H.Bokhari when the Lysander crashed during flying training at Peshawar. Bokhari survived the crash with slight injuries, but he resigned from flying shortly afterwards on September 10, 1942.

A confidential telegram R No 7318 dated December 20, 1941 from Foreign (Secretary), New Delhi to the Political Officer, Sikkim chillingly states:

IMMEDIATE

Much regret to inform you that Maharaj Kumar Paljor of Sikkim was killed in air accident this morning in Peshawar. He was flying himself and apparently stalled and crashed.

2. Please convey Viceroy’s sincere condolences to His Highness the Maharaja and add my own.

Information stored in the UK National Archives records the time of the accident as 10.50 AM, December 20,1941.

A copy of a demi-official letter dated the 21st December 1941, the Maharaja of Sikkim to the PO, Sikkim says: “I thank you very much for your kind letter of condolence. I was greatly shocked to know that Paljor’s end came so soon. However, I feel greatly relieved when I think that he sacrificed his life in attempting to serve the king and the country.”

Casualty Notification

Political Officer’s request to transport remains

The Maharaja’s note thanking the Government

The Maharaja further requested that his son’s body be brought back to Sikkim in a civil aircraft if available, and he would bear all the charges. However, the Defence Department (Air Branch) of the Government of India made a special concession and sanctioned the expenses for the conveyance of the body of the late P/O Namgyal from Peshawar to Sikkim under escort of a funeral party consisting of 2 Officers, 1 NCO and 6 airmen.

The funeral of the Crown Prince was held on 30 December 1941. My grandfather Tse Ten Tashi who was the Private Secretary- and friend- to the late Crown Prince was deputed by Maharaja Tashi Namgyal to receive and bring back the kubur (body) to Gangtok. Perhaps it is only fitting that his granddaughter is documenting for posterity the full flying journey of Pilot Officer Namgyal, Maharaj Kumar of Sikkim.

References:

- Charter of Incorporation, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, 1958

- Ramunny, M.(1997) The Sky was the Limit. Northern Book Centre, New Delhi.

- No 1 Service Flying Training School, Ambala- Operations Record Book

- Document Number AIR 29/565 held at the National Archives, Kew, UK

- File No 200-X/41 (Secret) held at the National Archives of India

- https://www.bharat-rakshak.com

- Pillarisetti, J (2017) The Westland Lysander- The IAF’s first monoplane bomber.

- Namgyal, Paljor. Common Wealth War Graves Commission Roll of Honour Second World War (1939-47)

- https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/blog/royal-indian-air-force

- https://indianairforce.nic.in/history-timeline

- 5th Pilots Course Batch

- RAF Accounted Airman Page

- The Endangered Archives by the British Library has many personal documents related to the Prince, including correspondence during his study years at St Joseph’s College in Darjeeling.