WHEN IAF TURNS INDUSTRIAL ENTREPRENEUR

Tucked away in Ojhar, 25 miles off Nasik on the Mumbai- Agra highway is 11 Base Repair Depot, one of the eight base repair depots of the Indian Air Force under overall control and supervision of the Maintenance Command, Nagpur. To the average Ojharite, this out-of-bounds “sarkari daftar” is an enigma. Save for the daily bouts of earth shaking decibels of aircraft engines being tested and deafening din of low flying aircraft, like the puzzled Ojharite, most of the nation is unaware of the performance every day by this industrial techno-yard of the Indian Air Force, where two variants of the MiG get a new life.

Since 1987, No. 11 BRD has set off an ambitious programme to overhaul the MiG variants with indigenous knowhow, developed by a qualified and highly motivated team of innovators that the nation can be proud of. The men in blue here are out to falsify not just notions and mindsets but nerve-racking, cynical calculations on a burdening, jinxed aircraft fleet. It is not just indigenisation that provides the vital edge to this overhaul project, but the mind-boggling cost-cuts it bestows on the exchequer in the MiG modernisation programme.

Stunning are the figures doled out by Air Commodore R.R. Bhardwaj, the Air Officer Commanding of No. 11 BRD. “The overhaul programme for the MiG-23s and MiG-29s, which would have cost over Rs 400 crores if undertaken in Russia is incurring not more than Rs 50 crores at No. 11 BRD, all with indigenous technology, under the highest quality standards and total technical life enhancement programmes and that too in the quickest possible time”. He can afford to be exuberant when his men confidently develop Life Extension Technology for a meagre Rs 50 lakhs, the alternative in Russia costing some hundred crores. Till date, 191 overhauled MiG-23s and 51 MiG- 29s have rolled out of the Depot and are back in IAF squadrons.

If lAF’s mastery on overhauling of the airframe and avionics are on abundant display here, senior officers concede that engines are still a far cry. Of the blighted MiG fleet in the IAF, it is the MiG-23 that really takes the epithet of ‘frequent crasher’, with the highest fatality rate. With the MiG-23 engines drawing flak from all quarters. No. 11 BRD had taken care to stay away from the fuss, bothering more on avionics and airframes and leaving the engine part to the HAL engineers at Koraput and No. 4 BRD in Kanpur.

|

|

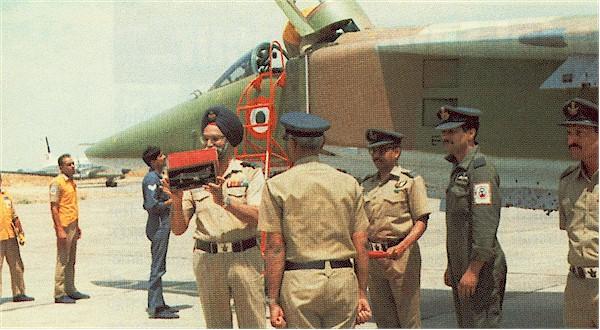

After the test flight of the last Sukhoi-7 overhauled by 11 BRD on 26th March 1982 |

Established in 1975 at the peak of modernisation programmes in the IAF, No. 11 BRD unveiled its operations with overhauling of Sukhoi Su-7s, only to last till the last such rolled out on 26 March 1982. Although, along with the slew of Repair Depots, No. 11 BRD was primed as the overhaul hub of IAF fighters, the transition from Su-7s to new generation MiG variants created an operational-gap for 11 BRD until the first arrivals of the MiG-23. Rebirth came in 1987 when the first MiG-23s came in for overhaul. After flight of the first overhauled MiG-23 in April 1988 and technology transfer for this aircraft from the Soviets in November that year, 11 BRD has not since looked back. Another major operational coup came in 1996 when the MiG-29s were allotted to 11 BRD for overhaul. The toil and the dedication received its just reward when the ISO 9001:2000 international certificates for quality standards were bestowed.

However, it was sheer global political circumstances that changed 11 BRD’s fortunes. With collapse of the Soviet Union, MiG spares were not easily forthcoming, forcing the BRDs to work on indigenising rotables and aggregates of avionics and airframes. Added to that, discrepancies arose in the Russian deliveries of spares and outsourced jigs and fixtures. When the Russian supplies became a problem, an Inter Agency Group for Life Extension was formed to work on indigenous life extension technology, “Russians were unyielding about pricing and had demanded Rs 400 crore for the whole process. When options ran out, we decided to take matters into our hands. What Russians did for Rs 22 crore for each aircraft, we did for below Rs 2 crore with our own indigenous life enhancement technology,” said a senior officer.

When the ageing aircraft started arriving in for refurbishment, the Air Force engineers and technicians had well defined tasks set for them. What they achieved ever since the MiG-23s came in from 1987 and MiG-29s from 1996, is beyond any definition. After giving the face lift for the aircraft, the final objective is to enhance its life cycle: MiG-23s having a technical life of 25 years would get more than five years extended life after the overhaul at Ojhar, and the MiG-29s with a destined life of 20 years or 2000 hours get 10 years or 1000 hours more to fly in Indian skies. Once “life extension” was declared as a thrust area, defence research labs throughout the country, HAL engineers and even IIT researchers were brought into the team for the operation. What started as a operation for life cycle enhancement soon metamorphosed into a movement for self reliance. There was not a single part of the aircraft that missed an attempt to indigenise. Other than the engine, everything from rotables, mandatory spares, radars to alloys and metals, BRD’s intrepid men “Indianised” anything in the MiG-23 on which they laid their hands!

|

| Air Marshal KS Bhatia, then AOC-in-C Maintenance Command, after the inagural test flight of MiG-23BN which was overhauled at 11BRD in 1988 |

Inside the operations hanger, the studious engineers of 11 BRD did not strive long to unearth the latent critical problems with the aircraft. The culprit in most critical snags of Russian made aircraft, says Wing Commander Tiwari, was the power supply module. With this ascertained, the only option left was to also indigenise this system. Interestingly, the 11 BRD- developed power supply module is “six times cheaper with performance ten times better than the Russian one”. Indigenisation itself was no silly game for the BRD men. Keeping a tradition of developing low cost spares. No. 11 BRD developed indigenous spares and components for well under Rs 1 crore when for those parts Russians had charged Rs 8-12 crores. It is self-reliance that has won laurels for 11 BRD. On constant move, the effort was always to indigenise as many parts as possible. The great deal of effort and success shown in this self-reliance foray is demonstrated by the fact that 11 BRD has achieved 96 percent indigenisation of the critical mandatory spares for MiG-29s.

|

A MiG-29 waiting to be inspected after overhaul at Ojhar. |

Sqn Ldr Sharnik Manna, who oversees overhauling of MiG- 29s describes: “The aircraft after wheeling in, is stripped of if engine, avionics, wings, fins and only the airframe’s skeleton remains. The MiG-29s have over 2000 types of parts, including nuts and bolts, and even the most minute one is arranged checked and the rotables are identified,” While all the rubberised items are replaced, the non-rubberised ones are recycled through a process of cleaning, followed by micro testing involving stringent quality standards to search for cracks and weigh’ dimensions and electroplated before being retained for reuse The whole set of looms or cables running across the aircraft are replaced completely. The engine is sent to the HAL’S Korapu plant and once back after overhaul, is checked with advanced internal scanning process before being integrated in the aircraft .

The whole process takes 296 days before test flight for the MiG-29s and 256 days for the MiG-23s. Although both aircraft go through similar process, the MiG-23s, with its exclusive swing-wing technology has to move through 14 stations of levels, while the MiG-29s have 13 stations. With minor differences in procedures, both aircraft go through disassembling in the first 2 to 4 stations, defect investigation’ between 4 to 8, rotable reassembling between 8 to 10 and total functional checks between 11 and 13. During all these stages the various processes are subjected to rigorous quality testing both by IAF and by external organisations, before going fo; independent post overhaul checking at the 13th or 14th level and the aircraft then taxied out for its first flight.

Concealed in a discreet comer is a specialist section working on composite materials for the MiG aircraft. With carbon glass as the ingredients, the BRD team has developed composite exteriors for the wings and fins of the aircraft to replace heavier alloys and metals, thereby reducing in considers amount weight of the aircraft and in the process, add tremendously to its speed and manoeuvrability.

| Fifteen Years after the first MiG-23BN was overhauled at Ojhar, the type still continues to be sent for overhauls. |  |

The day Vayu visited No. 11 BRD, one of the test pilots at 11 BRD, Sqn Ldr Chauhan was preparing for a third flight test sortie. “Usually an overhauled aircraft will have three test flights before being given the nod for return to the operational squadron. It is the test pilot who finally decides on giving the green signal. The aircraft has to satisfy all his parameters before the final affirmation.” Later, Vayu was to witness an impressive take and manoeuvring by Sqn Ldr Chauhan who was testing auto-pilot systems of a MiG-29.

No. 11 BRD is on cloud 9. Buoyant by the recent ISO certifications and high customer satisfaction inputs from IAF, 11 BRD is preparing steadily for the challenging years to come. With such cost effective technology and with proven manpower resources at its discretion, 11 BRD looks ahead to the day when its doors are opened for foreign customers to come calling for its services. Some nations in South t Asia have already experienced the irrefutable skills of No. 11 BRD. It would not be long before the Su-30s in Indian service land up at this revered techno-yard of the Indian Air Force.

Copyright: Vayu Aerospace Review