Squadron Leader Mahender Singh Pujji was in fact one of the first batch of 24 Indian ‘A’ licence holders to be accepted for service in the Air Force early during the Second World War. He received a Volunteer Reserve commission, trained with the Royal Air Force, and was awarded RAF wings. He flew in a combat role from emblematic RAF stations in the British Isles such as Kenley (one of the three main fighter stations defending London; and the operating base of “Sailor” Malan, Johnny Johnson, and earlier, of Douglas Bader), putting his life on the line to defend the British mainland; and flew in some of the Allies’ first offensive operations over Occupied France. He later flew briefly in the North African theatre, as well as extensively in the China / Burma / India theatre (and in the NWFP)

In recent years, the British have been re-discovering the contribution of ethnic minorities, particularly to their victory in the Second World War. For decades their war histories painted a picture of Britain “standing alone” for the first two years of the War, until the Americans joined them following the Japanese attack upon Pearl Harbor in December 1941. In point of fact – as some British historians have been among the first to point out – the British colonies of the time represented over 450 million people, and a considerable proportion of the world’s raw materials. These were not inconsiderable assets, to a country at war.

In recent years, the British have been re-discovering the contribution of ethnic minorities, particularly to their victory in the Second World War. For decades their war histories painted a picture of Britain “standing alone” for the first two years of the War, until the Americans joined them following the Japanese attack upon Pearl Harbor in December 1941. In point of fact – as some British historians have been among the first to point out – the British colonies of the time represented over 450 million people, and a considerable proportion of the world’s raw materials. These were not inconsiderable assets, to a country at war.

Today, with growing numbers of voters from first- and second-generation immigrant communities, and perhaps owing something to a belated sense of fair play, British politicians, journalists and historians have begun to recognize and re-tell the stories of some of the many people of non-European origin who served under their flag during the Second World War. It is even possible to purchase a study pack, at the Imperial War Museum, which documents the contributions of non-Europeans to the War.

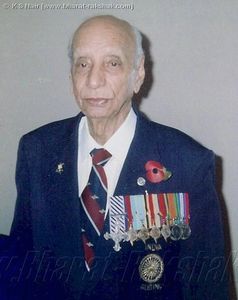

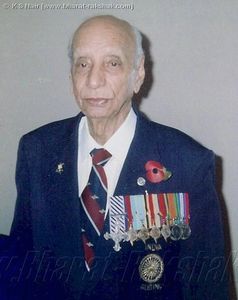

Among this material, and among these stories, there often appears one Indian pilot in particular: Squadron Leader Mahender Singh Pujji, DFC. He is easily accessible to British journalists and photographers, as he now lives in the UK; and is something of a poster boy for them, having flown operationally with RAF squadrons based in the Home Counties, and having been decorated with the Distinguished Flying Cross. He is also, as journalists have been quick to recognize, by nature, bearing and deportment, a simply wonderful figure to write about.

In the last ten years or so, this dignified Indian veteran has been interviewed for Our War, a compilation of the experiences of Commonwealth nationals during the War assembled by Christopher Somerville [1]; by the BBC; and by numerous newspapers and magazines. He has been featured in pictures on the RAF and the UK Ministry of Defence websites. He has in many ways become, in the UK, the visible face of the Indian contribution to the war effort.

Squadron Leader Mahender Singh Pujji was in fact one of the first batch of 24 Indian ‘A’ licence holders to be accepted for service in the Air Force early during the Second World War. He received a Volunteer Reserve commission, trained with the Royal Air Force, and was awarded RAF wings. He flew in a combat role from emblematic RAF stations in the British Isles such as Kenley (one of the three main fighter stations defending London; and the operating base of “Sailor” Malan, Johnny Johnson, and earlier, of Douglas Bader), putting his life on the line to defend the British mainland; and flew in some of the Allies’ first offensive operations over Occupied France. He later flew briefly in the North African theatre, as well as extensively in the China / Burma / India theatre (and in the NWFP). He is thus one of very few Indian pilots in the Second World War to have seen service in, and to wear the campaign stars of, all three theatres.

In Burma he flew with No 6 Squadron, serving as a Flight Commander under the legendary ‘Baba’ Mehar Singh. He also served as a Flight Commander with No 4 Squadron. Finally, he was awarded a DFC, for his work in Burma.

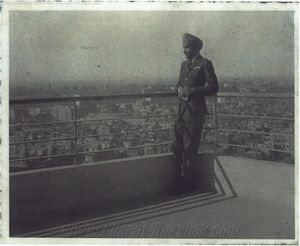

To an IAF history enthusiast, there can be few figures to compare with Sqn Ldr Pujji. Here is an Indian, who has flown Hurricanes and Spitfires from those grassy fields of England, captured in sepia-tinted photographs lounging between sorties on a Hurricane wing. There he is, a tall, spare figure clad in RAF summer rig, just as in every photograph of Battle of Britain aircrew we enthusiasts have ever pored over, but with his nationality unmistakable through his characteristic turban. He has also flown Curtiss Hawks in the desert theatre of Rommel’s Afrika Korps and Auchinleck’s Eighth Army, and spending time in Cairo during the time of the legendary Glubb Pasha. And he came back to fly Hurricanes and Lysanders over the hostile, Forgotten War environs of the North West Frontier and the jungles of Burma. What stories he must have to tell!

So it was a very special day, one sunny autumn day sixty years after the war’s end, when I had the indescribable privilege of meeting Sqn Ldr Pujji. As it happens, I was introduced to him by that wonderfully supportive friend of this site, Sqn Ldr Ian Loughran, VM, a swashbuckling veteran of Nos 7, 20 and 23 Squadrons. Listening to these two officers reminisce, over a cup of tea, was one of the high spots of several years’ pursuit of IAF veterans’ stories.

Sqn Ldr Pujji is enormously courteous and accessible, but in a certain sense, difficult to interview – in the sense that it is not possible to pin him down and cross-examine him on some of the detail we would be interested in. For one thing, he himself has asked interviewers not to press him for too much detail about his experiences of combat, as many of those memories are clearly increasingly painful for him. For another, his logbook is no longer available – of which more later in this article.

But for this admirer it was enough to listen to him, a man who has lived so many of those stories and experienced so many of those episodes that form the heart of the western memory of the Second World War, reminisce about what he is willing to share. So here – with added detail from some of the public domain information and other interviews he has given – are some of Sqn Ldr Pujji’s stories:

Early Years

Mahender Singh Pujji was born in Simla, on 14 August 1918. His father was a gazetted officer in the Department of Health and Education – a very senior and respectable “establishment” position for an Indian in those years.

He attended Sir Harcourt Butler High School in Simla. His father retired and moved to his home state of the Punjab around the time he finished school. He joined college initially at Government College in Lahore, and moved later to Hindu College in the same city.

Pujji learned to fly as a hobby, and received his ‘A’ licence in April 1937. His first job was as a line pilot with Himalayan Airways, which flew passengers between Hardwar and Badrinath. He was “offered a better job” by Burmah Shell, and went to work for them as a Refuelling Superintendent in 1938. The Second World War broke out in September 1939, and in December that year he applied in response to advertisement in the newspapers inviting applications from ‘A’ licence holders, for a Volunteer Reserve commission in the Indian Air Force.

Despite the fact that the Indian Air Force had been nominally established in 1933, there had been very little growth since its first flight was raised that year with five Cranwell-trained pilots. At the outbreak of the Second World War, six years after its formation, the Indian Air Force still mustered just the same single squadron with which it had been established.

Even after the war started, the (then still-British) Government of India does not initially appear to have had much sense of urgency about expanding the IAF. However they did follow some of the same expansion measures that His Majesty’s Government was embarking upon at the time in the UK. One of these was to offer Volunteer Reserve commissions in the Air Force to anyone who held an ‘A’ licence from a flying club (roughly equivalent to a CPL today) in India.

The young MS Pujji was one of the first batch of twenty-four Indians to be accepted into the IAF through this route. Ten of them were killed in action or in flying accidents, in the UK. “No one remembers,” he says, gently as he says everything, but with an unmistakable tinge of bitterness.

In early 1940 MS Pujji was interviewed by a panel of RAF officers in Ambala, and accepted. He was commissioned on 1st August 1940, into what became the 4th Pilots’ Course, of the Indian Air Force. He was immediately seconded to the Royal Air Force, and sent to to the UK.

The First Twenty Four in the UK

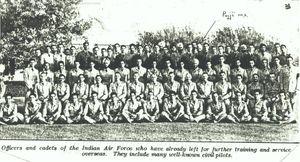

| The First Twenty-Four, before departure for the UK. Interestingly, it seems they are already wearing winter uniforms, while others in the picture seem to be wearing summer uniforms. The 24 were a select few from the 4th Pilots Course so chosen to go to the United Kingdom.

See more in Album : Sqn Ldr M S Pujji DFC – In defence of Great Britain

|

|

All the First Twenty Four traveled together, a small contribution from India to the Allied cause, at this early stage of the War. Besides Pujji, they included H C Dewan, Ranjan Dutt, Ehrlich Pinto, and Shivdev Singh, all of whom were to become Air Marshals in the post-Independence Indian Air Force.

They traveled by sea, aboard the SS Strathallan, and reached Liverpool on 1st October 1940.

“Our ship stopped in South Africa. I was shocked to see the treatment of Indians and Africans there. I and my colleagues were very angry.”

The Battle of Britain was in full swing during their sea voyage, and was just winding down when the First Twenty Four arrived in the UK, although the fact was not immediately perceptible to the British. (Hitler had, without much fuss, cancelled Operation Sea Lion, the planned invasion of Britain, on 17 September; and was already turning his mind to the attack on the Soviet Union.) Among the first visible volunteers from British overseas possessions, the First Twenty Four received “huge publicity”, Sqn Ldr Pujji says; and were invited to tea at Windsor Castle, with the Royal Family, and with the Secretary of State Emory.

Plt Offr Pujji’s first posting was to No 1 RAF Depot in Uxbridge, and took effect on 8 October 1940. No one would have realized it at the time, but that was the anniversary of a significant date in Indian aviation history, the date the IAF Act had been passed, eight years earlier. (It was not until the late 1970s that that date came to be marked, as Air Force Day, in India.)

Plt Offr Pujji’s posting to Uxbridge was as a “supernumerary, pending military flying training”; and within a few days he was posted to No 12 EFTS at RAF Prestwick, to undergo flying training on de Havilland Moths. He and his batch were subjected to an “abbreviated course”, with “seven or eight” subjects to pass; then went on to undergo Advanced flying training at No 9 Service Flying Training School at RAF Hullavington. They completed the course, and received their RAF wings, on 16 April 1941.

A week later Plt Offr Pujji and a handful of the others from the First Twenty Four went to the famous No 56 OTU at RAF Sutton Bridge. Others there with Pujji from among the First Twenty Four included Ranjan Dutt and HC Mehta. Among the other pupils there at the same time was a batch of Polish pilots.

| With Polish pilots at No 56 OTU, RAF Sutton Bridge, 1941 – printed from reverse side of negative? The Polish pilots wear their own pilots badges, which are visibly different in shape from the RAF wings

See more in Album : Sqn Ldr M S Pujji DFC – In defence of Great Britain

|

|

In later years the same sequence of flying training, and even the same names for the flying schools (EFTS to SFTS to OTU), were to be reproduced in India – there were No 1 EFTS at Begumpet, and No 2 EFTS at Jodhpur (later to briefly become AFFC); there was No 1 SFTS at Ambala (later to become No 1 AFA and move to Begumpet); and No 151 OTU at Risalpur. But all that was still a few years in the future, when Mahinder Pujji and his small band of countrymen were on their journeys to RAF training and RAF service (and indeed, death in RAF service, for many), before, for some of them, IAF service.

Plt Offr Mahender Singh Pujji served in the UK with two prominent front-line fighter squadrons. His first operational posting was to the famous No 43 Squadron, the “Fighting Cocks”, effective 2 June 1941. This squadron was something of an elite squadron in the RAF. Formed in 1916, during the First World War, its first CO was then-Major W Sholto-Douglas, who as an Air Chief Marshal was AOC-in-C Fighter Command for part of the Second World War. It was based for many years at RAF Tangmere alongside No 1 Squadron, and famed for its displays at the pre-war Hendon air shows (some, in early years, with the aircraft tied together!). It was the nursery of many great pilots who were to serve later in India – including the almost-legendary Group Captain FR “Chota” Carey, who passed away in December 2004.

However, 43 Squadron was moved north to Drem in Scotland for a rest around this period, so later the same month Pujji was posted to No 258 Squadron, RAF. 258 Squadron had only recently moved into the operational area, coming South from the Isle of Man towards the end of April 1941. The squadron spent the rest of the year based successively at Kenley, Redhill and Martlesham Heath, carrying out sweeps over France and patrols over coastal shipping[2].

Squadron Service in the UK

Plt Offr Pujji spent nearly three months flying operationally from RAF Kenley, flying coastal patrol and other operational sorties in defence of the UK, and taking the war to the enemy by way of fighter rhubarbs and bomber escort over Occupied France.

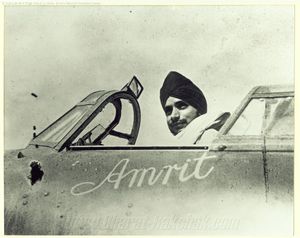

Photographs from that period show Plt Offr Pujji in the cockpit of a Hurricane or standing on the wing, with the name “Amrit” painted just below the cockpit. “My fiancee at that time,” he explains, with a tender smile even now; she was later to become his wife of several decades.

He says of that period, poignantly:

“We were escorting bombers to Occupied France. We went there in the morning, in the afternoon and in the evening, three times a day. The risk at that time was so great that hardly ever did all of us come back safe. Every morning there would be two or three pilots less sitting around the breakfast table … “

In more detail, in the BBC interview referred to above, he has said:

“My first action was a sweep across occupied France escorting our bombers. I was flying through what looked like flowers. I couldn’t hear anything over the engine, all I could see was these beautiful things bursting around me.

I was curious rather than scared. I didn’t realise this was anti-aircraft fire directed at us. Very soon a bomber was shot down and then I realised.

The first of our pilots to be shot down was my roommate. Waking up at night and being alone gave me a sad feeling. I soon got over that because everyday someone went missing.

On my first day there were 30 pilots at breakfast and we were never 30 again. Men were always being shot down or bailing out. It never happened that we all returned from a mission.

We were supposed to be able to take off in one minute. In my first week I almost broke the record – running from the place where we waited listening to music …

The RAF officers appreciated that and I was very much respected. They treated me better than anyone else, but that’s perhaps because I wore a turban and was a bit of a novelty.

I got VIP treatment. I never liked English food and hardly took any lunch or dinner. The authorities asked what I wanted, and the only thing I could think of was chocolate. It was rationed, but I was supplied with extra and was given two eggs for breakfast.

When I had done my quota of sorties I was due for a three-month rest, but I wanted to fly. They offered to send me to Russia, which Hitler had just invaded. I said: ‘Yes, anywhere, but I must fly.'”

His flight commander was killed, and he recalls that he assumed the acting role of Flight Commander for a brief period. This itself would have been unusual, for the time – for an Indian to hold acting command of a flight, in an RAF squadron in the UK.

In a different interview, he has said,

“On one occasion I suddenly found that my dashboard was gone – I didn’t notice because of the noise of the engine. A bullet had passed through my jacket and the whole of the dashboard was shattered. Then black smoke and oil started coming from the front of the engine at about 18,000 feet. I started to glide over the English Channel. At 7,000 feet I was advised by radio to bale out of the plane over the Channel where I would be picked up by a boat in the area. But as I could not swim and did not like the idea of jumping out of the plane I told base that I would try to make a forced landing. I was encouraged when I saw the white cliffs of Dover, and everything was going fine until I opened up my landing gear and the plane burst into flames. I managed to crash-land the plane and was dragged from the burning wreckage. I spent the next seven or eight days in hospital.

The day I shot down my first aeroplane, I went into my room and lay down – I didn’t want to talk to anyone. What I had gone through – that could have been my death, you see.”

When you meet him today, he comports himself with immense calmness and dignity, and it is easy to imagine him as a 23-year old in RAF uniform, high-spirited like all who wore Air Force uniform in those days, but striding the streets of the UK with the same dignity he exudes now. He himself seems clear that during those years at least he did not experience the racism or discrimination that has marred some Indians’ experience of living in the UK:

“When I was in England during the war I was treated very well indeed. I had my own driver and petrol was paid for. When I went to the cinema I used to get in the queue with everyone else, but people would insist that I got to the front of the queue – I think it must have been my uniform. I would get to the front of the queue and try to pay for my ticket, but was let in free. Similar things happened at restaurants in the village; often the owners would not take payment for a meal. I felt very welcome indeed, I never felt different or an outsider and my experiences in this country made me keen to return some time after the war. I was made to feel very much at home by everyone I met.”

The way these things are determined, he qualifies for the Air Crew Europe campaign star, but does not qualify for the Battle of Britain clasp, as the eligibility for that clasp requires having flown an operational sortie in the UK before 31 October 1940. Pujji arrived in the UK only on the 1st of October that year, and started flying operationally only in June 1941. The omission does nothing to alter his quiet confidence in his own contribution to the air defence of Great Britain, and the debt the British owe him. He wrote to the British authorities about it, he says. Not qualified for the Battle of Britain clasp? “Then whose battle was it, that I was flying in, day in and day out?” he asks, quietly.

North Africa and the Western Desert

At the end of September 1941 he was posted to Air Headquarters, Western Desert. He flew operationally again, mainly with an American Mohawk squadron; and at the end of December went into the Middle East pilots’ Pool.

North Africa was a much more primitive theatre than Europe; and Pujji found the food a particular turn-off. But there was plenty of flying, and that kept him happy; though much of it was the down-and-dirty business of close air support. The RAF used fighters for CAS in North Africa (as they were to do later in Burma), rather than the light bombers that its CAS doctrine had previously called for. The battle was ebbing and flowing, but Tobruk was still holding out at this time – it was the period of Auchinleck’s Operation CRUSADER.

He lived through that period, he says, on biscuits – “You needed a hammer to break them,” he says, with feeling; and he wouldn’t eat the bully beef which was often the only garnish available. “Then they sent me every weekend to Cairo – one aircraft had to go every weekend, they let me fly it, so I could go and have a decent meal!” Cairo in those days was something of a R&R centre for the North Africa and Middle East theatre, a cosmopolitan city with a large Allied presence, plenty of night life and good cuisine.

During this period, Pujji was once shot down by ground fire. In his own words, again from another interview:

“I was in a Kittyhawk and … my instrument panel suddenly shattered. … Later I found that a bullet had gone through my overalls – the same one that had shattered the panel. I preserved that as a souvenir for many years.

Then … suddenly the aeroplane started disintegrating. I immediately throttled back and landed … in the middle of the desert, right in the sand. Every aeroplane had water and these sort of things, so I sat on top of the aircraft, waiting. I knew to the north was the Mediterranean Sea – I couldn’t walk that far. South, east and west there was nothing. There was no choice for me …

I was there for about nine-ten hours, when I saw a dust column. As it happened, it was our soldiers … retreating. I was picked up.”

On 16 January 1942 (just before Rommel’s second offensive, as it happens, which successfully took Tobruk), he embarked at Suez for Colombo.

Back in India

In February 1942, MS Pujji and others from the First Twenty Four, who had returned from the UK, were posted to No. 4 Squadron of the Indian Air Force, at Kohat, flying the Westland Lysander. The Squadron CO was MK Janjua.

Perhaps somewhat surprisingly for a man who has flown over Europe, the Middle East and Burma during the Second World War, it is this flying, over the North West Frontier Province, that Pujji describes as the “most dangerous” experience of his life. An RAF pilot flying from Miranshah at the same time, who was shot down and fell into the hands of Sarhaddi rebels, was “literally cut to pieces”.

Through 1943 he flew Lysanders and Hurricanes in a variety of locations in India.

On 20 December 1943 he was posted to No 6 Squadron at Cox’s Bazaar. Although flying Hurricanes again, this was a tactical role, rather than a fighter role; however, it was crucial to both 14th Army and to 3rd Tactical Air Force.

In March 1944 he moved with the squadron to the Buthidaung area, which was at the time the scene of a major ground battle.

In April 1944 he was transferred to No 4 Squadron, also Hurricane-equipped and based at Feni. The squadron carried out transport escort and merchant shipping escort. The Squadron was under the command of Sqn Ldr Geoffrey Stanton Sharp RNZAF.

In June, No 4 Squadron transferred to Comilla (now in modern-day Bangladesh), and later formally relieved Pujji’s old squadron, No 6, in its Fighter Reconnaissance role for 14th Army.

With the outbreak of the monsoon, the role of the squadron was changed, from Fighter Reconnaissance to light bombing. They saw action along the Sangu River, during the Third Arakan campaign. There were four IAF squadrons operating in the area, with two more joining in 1945.

Early in 1945, Acting Flight Lieutenant MS Pujji was transferred on attachment to Staff College (then in Quetta, in today’s Pakistan).

He had spent almost four years continuously on operational flying – unusual even by the standards of the Second World War. It was not fun and games – during his time in action, Pujji says, “I lost thirty-five pilots.” There is still a sense of loss in his voice, as he recounts this.

In the earlier BBC interview, which I read several years before I had the privilege to meet him, he had said:

“I remember my dead friends all the time. I have the photographs with me where I marked crosses over the pilots we lost. It’s something I can’t forget.”

Consider this amateur historian’s feelings, that day, when he showed me his albums, with those very photographs, marked as he said with crosses … [3]

Sqn Ldr Pujji’s DFC citation reads, in part:

Acting Flight Lieutenant Mahinder Singh Pujji RIAF No 4 (IAF) Squadron:

This officer has flown on many reconnaissance sorties over Japanese occupied territory, often in adverse monsoon weather. He has obtained much valuable information on enemy troop movements and dispositions, which enabled an air offensive to be maintained against the Japanese troops throughout the monsoon. Flight Lieutenant Pujji has shown himself to be a skilful and determined pilot who has always displayed outstanding leadership and courage.

The DFC was announced in the London Gazette on 13 April 1945

After the War

Shortly after the war, in late 1946, Sqn Ldr Pujji was diagnosed as suffering from tuberculosis.

He was invalided from service on 10 January 1947, with 100% disability. Doctors’ assessment at the time was that he had only six months to live. TB in those days was even more often fatal than it is today.

Pujji spent over eight months in hospital, part of it in Kasauli. His spirit remained as indomitable as ever; he organized theatrical productions, with other patients making up the cast, while in hospital. Happily, he did eventually survive his bout with TB; but was classified permanently unfit for service. He left the Royal Indian Air Force and took up the position of Aerodrome Officer at Safdarjung Aerodrome in Delhi.

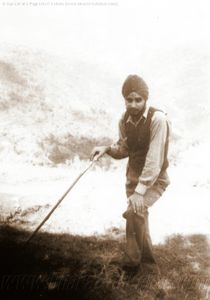

He continued to fly, in his civilian role; and became a prominent member of the nascent gliding movement in India. He participated in air races and gliding events. He once glided from Pune to Belgaum, over 10,000 foot hills, non-stop. He taught two young women (he is old-fashioned enough to refer to them by the now probably politically-incorrect term “girls”) aerobatics on gliders – he recalls with a smile that they flew, and executed their aerobatics, in saris. They were such a novelty that Nehru specifically met them, on a visit to the gliding club.

In 1968 he went to the World Gliding Championship at Leszno in Poland, as the team manager for the Indian team. This was the only year that India participated in this event. It was an exciting event; with some argument over the admissibility of points accumulated on one particular day when several of the participating pilots’ barographs (supplied by the organizers, to monitor the observance of an altitude restriction) malfunctioned. One of the participating pilots in India’s team was Squadron Leader Ian Loughran, India’s first FAI-recognized diamond pin holder.

Parting Thought : The Logbook that was ‘borrowed’

|

Sqn Ldr MS Pujji in 2004. He is wearing his medals with his DFC first, his FAI gliding pin in his right lapel, a poppy (symbolizing remembrance of those who fell in battle) plus his Burma Star Association pin on his left lapel, his India gliding team blazer, and an RAF tie .

Pujji is one of the select few Indian Air Force officers who had earned the Air Crew Europe Star and the even rare Africa Star.

See more in Album : Sqn Ldr MS Pujji DFC – Middle East, Burma, India

|

Sqn Ldr Pujji’s logbook was “borrowed” by a journalist in the UK, who claimed to be writing an article about Second World War pilots. The journalist has not been seen or heard from since then. It may be cynical – but perhaps not – to wonder if the “journalist” in question is holding on to the logbook till he can sell it. There are forums, it has to be said, where the authentic logbook of a Second World War pilot with a DFC can be sold for a tidy sum.

If this article can persuade anyone who encounters Sqn Ldr Pujji’s logbook for sale to point out the provenance and ensures it is returned to Sqn Ldr Pujji, then we will all have made a small contribution to journalistic, historic and personal honesty.

Notes:

1. Broadcaster and author, and grandson of the wartime Vice-Admiral (later Admiral of the Fleet) Sir James Somerville, Flag Officer Commanding of the famous Force H. Somerville’s book has been an invaluable contribution to our own awareness of Indian contributions to WW2. Our War has some of the earliest published material on Sqn Ldr Pujji; on later-Major-General Dinesh “Danny” Misra, MC; and on Noor Inayat Khan, GC, of the SOE; among other Indians who participated in WW2.

2. No. 258 Squadron RAF, was later to have a South-East Asia Command chapter in its history, its number being used to designate an ad hoc Hurricane squadron operating from Colombo (partly, in fact, from a makeshift strip on the Racecourse within the city), which acquitted itself in combat against Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s First Air Fleet (the same carrier battle group that had devastated Pearl Harbor) in April 1942. It also served in Burma, and was briefly in Madras between operational commitments.

3. Since then, one of those poignant photographs has appeared in Sqn Ldr Rana Chhina’s evocative book, The Eagle Strikes.

Recommended Links:

The First Twenty Four – Photos and Particulars of all the 24 UK trained Indian Air Force Officers.

Sqn Ldr MS Pujji DFC: ‘I knew England was having a rough time’ BBC Website

‘There were no parades for us’ Pujji talks to Simon Rogers on the Guardian Website.

Audio: ‘I lived on bread and milk for three days’ Pujji talks to Simon Rogers about his early experiences after leaving India to join the RAF. (4min 58s)

Audio: ‘I forgot to put the wheels down’ his early pilot training on Hurricanes. (4min 16s)

Audio: ‘It was thrilling’ his first combat mission, over enemy territory. (4min 32s)

Audio: Fighting for Empire – Audio Interview on BBC

Action Required!

We embed Facebook Comments plugin to allow you to leave comment at our website using your Facebook account. It may collects your IP address, your web browser User Agent, store and retrieve cookies on your browser, embed additional tracking, and monitor your interaction with the commenting interface, including correlating your Facebook account with whatever action you take within the interface (such as “liking” someone’s comment, replying to other comments), if you are logged into Facebook. For more information about how this data may be used, please see Facebook’s data privacy policy: https://www.facebook.com/about/privacy/update.

Accept Decline

In recent years, the British have been re-discovering the contribution of ethnic minorities, particularly to their victory in the Second World War. For decades their war histories painted a picture of Britain “standing alone” for the first two years of the War, until the Americans joined them following the Japanese attack upon Pearl Harbor in December 1941. In point of fact – as some British historians have been among the first to point out – the British colonies of the time represented over 450 million people, and a considerable proportion of the world’s raw materials. These were not inconsiderable assets, to a country at war.

In recent years, the British have been re-discovering the contribution of ethnic minorities, particularly to their victory in the Second World War. For decades their war histories painted a picture of Britain “standing alone” for the first two years of the War, until the Americans joined them following the Japanese attack upon Pearl Harbor in December 1941. In point of fact – as some British historians have been among the first to point out – the British colonies of the time represented over 450 million people, and a considerable proportion of the world’s raw materials. These were not inconsiderable assets, to a country at war.