22nd April. Under XXXIII Corps, the 7th and 20th Divisions and 254 Tank Brigade moving down the Irrawaddy River Axis reached Magwe by 19th April. Tactical Air units continued close support of these two drives and as airfields were captured, air units moved up to give close air support.

No. 7 Squadron supported XXXIII Corps in its unstoppable advance down central Burma. The speed of the advance increased the difficulties of communication between the forward units of the advancing Allied forces and the rear headquarters. The hard pressed Japanese forces were scattered in the jungles on either side of the Irrawaddy River.

The situation had become so fluid that effective ground intelligence was next to impossible. As a result, XXXIII Corps became heavily dependent on the tactical and Arial and photo reconnaissance of the Air force.

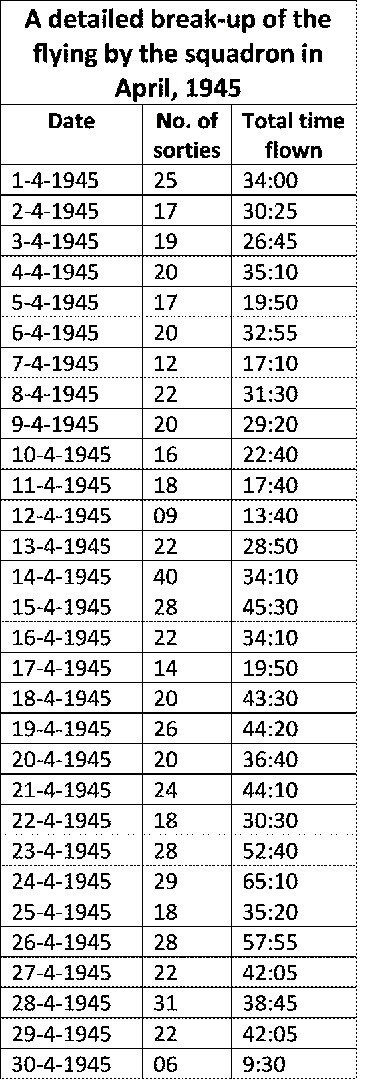

In April, 1945, the squadron flew a record 1033 hours of Operational Flying. The aircrew were in the air flying almost daily, and most of the pilots were logging more the one sortie a day.

The British-Indian Army made rapid advances into Burma moving southwards. This resulted in the pilots having to carry our longer sorties. The furthest point being Prome some 200 miles from the squadron’s base at Sinthe.

Since the front was moving south so quickly and deeper, that on 1st May, 1945, the squadron had to relocate to Magwe in order to remain within the operational flying range. The squadron headquarters

* Note the squadron flew each day in April

was set-up in Maida Vale three miles from Magwe. Also Co-located at Magwe were Nos. 11 and 42 squadrons flying Hurricanes and RAF’s No. 152 squadron flying Spitfires. Their prime task was to provide close tactical air reconnaissance support to XXXIII Corps over the Irrawaddy River between Magwe, Bassein and Rangoon.

The prime task for the squadron consisted of low flying for Photo reconnaissance. Thus making the aircraft vulnerable to enemy ground fire. On this account the squadron lost few aircraft and pilots. On 14th Apr 44, Fg Offr. JS Kochar flying a Hurricane lost airspeed in a turn while dropping a message to the XXXIII Corps HQ and was killed in the impact. The squadron’s aircraft used to fly down the Irrawaddy River which had hills on both banks Two weeks later the first casualty due to hostile action occurred, when some of the pilots reported that on one sortie the lead aircraft had run into a steel cable stretched across the river from one bank to the other. In fact, overnight, the Japanese had installed steel cables at various points across the river at approximately the height these aircraft used to fly. It was unfortunate that on that day, the lead aircraft flown by Fg Offr. KR Rao went straight into one of the cables and crashed, thus, killing him. No. 11 squadron’s Medical Officer, was killed outside the camp’s perimeter on 8th April, 1945, where he unluckily came across a Japanese patrol. On 14th April 1944, the squadron’s Fg Offr. JS Kochar flying a Hurricane lost airspeed in a turn while dropping a message to the XXXIII Corps HQ and was killed in the impact. Fg Offr. NS Prasad was shot down and killed by ground fire two days later over the same area.

In spite of the mishaps, the morale in the squadron remained high. In the month of April saw the Squadron carried out a fantastic total of 1033 hours of flying, which was unequalled by any other Squadron in the 221 Group.

Air Commodore M Bhaskaran (Retired) had in 1973, narrated an interesting incident during the squadron’s 2nd tour when the Japanese were not the enemy. At the time of the incident narrated below, he was a Pilot Officer and one of the squadrons engineering officers.

As per him:

“PC Lal and PJ Mathew once flew together from Sinthe. 10 minutes after take-off, they both came back over the airfield I went out to the dispersal hut and looked up wondering whether there had been a technical snag in the machine.

While Lal circled, Mathew peeled off and came into land. He did not do the usual circuit over the airfield. I thought he must be in trouble, and leaned forward to have a good look. Mathew (nick-named ‘Pop Mathew’), lowered his undercarriage and flaps and came in slowly. It seemed there was something tight in the way he handled the machine. It shuddered to a halt and I ran to the cockpit.

Pop jumped out of the aircraft and began running towards me. ‘What happened” I asked in Malayalam. Panting, pop pointed out and we slowly went back. “A bloody snake was around my control column”. ‘God, how the hell did you manage” I asked. “I had to, otherwise, I was a goner. He was coiled around the middle of it and I was saved by the helmet and goggles and my gloves. He 9the snake) looked at me and the blighter knew he had me there. I had to ease the stick ever so gradually. I think the bastard is still there. Get someone to get him out”.

I yelled for the mechanics, and a few with sticks went to the cockpit and saw that the snake had had enough of flying. It slowly came over the canopy, which was now pulled back, he went down the down the wheels and on to the tarmac and thence to a patch of grass, and a minute later the snake was invisible. The snake was green”.

Air Chief Marshal PC Lal in his book “My Years with the IAF” had described an incident which goes as follows:

The same Matthews, we called him ‘Budha’ as he was the oldest in the squadron was out on a sortie. By then the Japanese were on the run. We were anxious to see that they did not get away by boat out into the open sea to their waiting ships. So we used to do aerial recces in the delta area looking for Japanese ships. Matthews was in one of those sorties. His number two was Dolly Engineer. Obviously, there were some Japanese hidden in the Mangrove swamps. They shot Matthews’ aircraft which crashed into the swamp. Engineer reported it…………Engineer circled over the aircraft to see if the hood would open. There was no movement. Engineer came back and reported that Matthews was probably gone. We sent out search parties but got no news. Two weeks later our troops entered Rangoon, and a few days after that, on 23rd May, 1945, by which time we were based at an airfield called Maida vale-I received a message saying the a man had been picked up who had no clothes on him. He was obviously an Indian, not Burmese, and was wrapped in a parachute. He had been picked up by an Indian Naval Vessel in the delta area and brought to Rangoon. He had no identification mark on him. He had been left in an Army hospital. Could he possibly be our man?

I flew down immediately to Rangoon, went to the Army hospital and found our friend Budha Matthews! He said that when his aircraft was shot down, he was in a state of shock. He was injured also, badly in the back and also in his ribs and back. He could not open the cockpit hood and he could see the water. He knew he was at the mercy of the sea and that the rising tide would soon drown him. He was conscious, but unable to do a thing.

After half an hour or so, a little canoe appeared with an American in it. He opened the hood, pulled Matthews out, put him the canoe and took him away to a little island where he had built a camp for himself well hidden in the mangrove swamp. He belonged to a American Secret Service force which the Americans had deployed in the area, as they were also on the lookout for the Japanese. He had a wireless set and he was keeping track of how many Japanese were going in which direction. He saw an aeroplane which had RAF markings (at that time we did not have IAF markings), being shot down. So he went and rescued the pilot, and found that he was an Indian.

Matthews was so badly injured that the American had to cut Mathews’ clothing in order to get him to his room and the only thing the American was left with to wrap him in was the parachute which Matthews wore around him like a shirt or a chador (sheet). The American kept a lookout and when an Indian Naval vessel was going past, he managed to send it a signal. They picked up Matthews and he explained, I am sorry I can’t identify him, but he was in an aeroplane which has now disappeared underwater. It was already fairly deep in the mud, and when the tide came in, it washed the aircraft away.

Normally the parachute should have gone back to the parachute section, but it was so blood-stained and damaged, that he decided to keep it. Matthews got three quarters of it and I got one quarter. Enough to make me a shirt which I wore for many years. It was truly a miraculous escape and rescue!

The month of May 1945 saw allied forces go further south into Burma in pursuit of the retreating Japanese forces. Rangoon was captured by the Allied forces on 3rd May, 1945.

During April-May 1945, the squadron had flown more Operational Hours than any squadron in the Central Burma front. The serviceability of their aircraft in April was at an impressible level of 97% and during May at 99.4%. Only those who had to service aircraft in ankle deep mud of the ‘kutcha strips’ of Burma knew just how great this achievement in serviceability was.

Air Vice Marshal Vincent, commanding 221 Group, visited the squadron on 15th May, 1945 and praised the squadron’s personnel for their excellent work and the number of hours they had put-in during April, for in that month itself, as mentioned earlier, the squadron flew a record 1033 hours of Operational Flying. The aircrew were in the air flying almost daily, and most of the pilots were logging more the one sortie a day. The squadron’s role by then had more or less come to an end by then and this was compounded by the fact that by the end of May the monsoons had set in. The second tour of the squadron in the Burma front came to an end on 23rd May 1945 when the squadron began to prepare to return to India to Quetta.

On 26th May 1945, the squadron commenced their move out of Burma to Quetta in Baluchistan waiting for the war to end.

As a token of their appreciation, the 33 Indian Corps presented the squadron with a trophy of a metal Pagoda on which is inscribed, “From XXXIII Indian Corps with most appreciative thanks for the excellent support given to the Burma campaign”.

The Squadron moved to Samungli in June 1945. And from then till the Japanese surrender in August 45, carried out mundane duties like DDT spraying and leaflet dropping over the NWFP. Sqn Ldr. Lal handed over command to HC Dewan in Sept 1945. In November 1945, the Squadron reequipped with the Supermarine Spitfire, after moving to Gwalior.

In October 1945, for his leadership of the squadron in the unit’s second tour of Operations, Sqn Ldr. Lal was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC), the last such award given to the IAF in WW II.

His DFC citation is as follows:

“Sqn. Ldr Lal has completed a number of operational sorties, he is the commanding officer of a squadron which has been employed in photographic reconnaissance in support of the Fourteenth Army in the Irrawaddy valley. He has shown exceptional qualities and keenness and has completed many hazardous sorties in the wake of strong enemy opposition. He has frequently penetrated deep into enemy territory in search of important information. By his coolness and determination, Sqn Ldr. Lal has set a fine example to all his pilots”.

Further Reading:

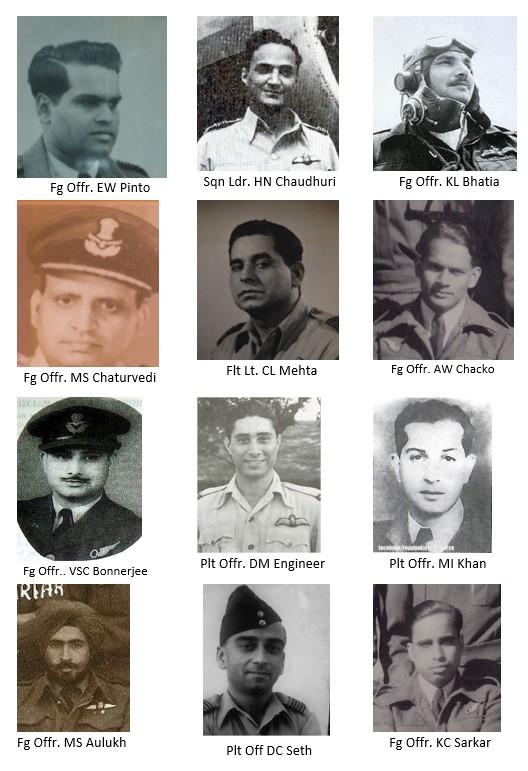

Sqn Ldr H N Chaudhari – First Commanding Officer

Hi,

Aside from P.C. Lal’s ‘My Years With The IAF’, is there any other book that covers the Indian Air Force operations in WW 2?

And thank you for all the effort on this website — I enjoy it very much.

Cheers,

AW

KS Nair’s “Forgotten Few”, S Sapru’s “Combat Lore” are two

Thank you

Thank you