Squadron’s First Operation (Taste of Blood)

The first taste of action that the squadron was tasked with was over Northern Waziristan. On 3rd Dec 1943, when Fg Offr. KL Bhatia with navigator Fg Offr. V Srihari, and Flt Lt. PC Lal with navigator Flt Lt. Sarkar, dive bombed targets near the Tochi River. This has also been mentioned in the squadron’s Operations Record Book which reads as under:

03.12.43 time 08:00 “Two aircraft of this squadron did their first Operational sortie over Waziristan. The pilots did a preliminary reconnaissance in Audax aircraft, after which they proceeded to bomb with 2 x 500 lbs. each. The leader Fg Offr. KL Bhatia, got a direct hit. The aircraft operated from Miranshah”.

The local Political Agent observed the bombing while flying in a Harvard as a passenger.

Again on 21st Dec. 1943, Fg Offr. KL Bhatia carried out similar Dive Bombing operational sorties over the enemy.

The squadron also operated from Miranshah with its fort overlooking the dirt strip, where the aircrew came under direct enemy fire when insurgent tribal snipers fired at them in the darkness. For safety reasons, each night the aircraft had to be pushed inside the fort.

There is an interesting entry in the Squadron’s ORB for the 8th December, 1943, which states:

“Fg Offr. Pinto was promoted to the rank of A/ Flt Lt, took over command of the detachment flight at Nagpur.

Flt Lt Pinto threw a party to the personnel of his flight. All girls interested in the Air Force joined the party”.

Precursor to the Squadron’s Move to the World War II Theatre

Pending transfer to the Burma front, the unit was delegated to go to Maharajpur, Gwalior to carry out Close Support Exercises in cooperation with an Army formation. It was during this move that the squadron suffered its worst series of mishaps. While the first batch of two aircraft being ferried made the flight to Maharajpur Gwalior safely, the second batch of aircraft had run into poor visibility and dust storms. Of the nine aircraft that flew in this batch on 19th Feb 1943, three crashed. Two pilots Fg Offr. Rachpal Singh and Fg Offr. Ajit Singh with their respective gunners were killed, while Fg Offr. Gocal and his Gunner Flt. Sgt Ghosh survived their crash landing at Lahore aerodrome. The remaining air party was forced to land at Delhi taking off next day, arrived at Maharajpur Gwalior.

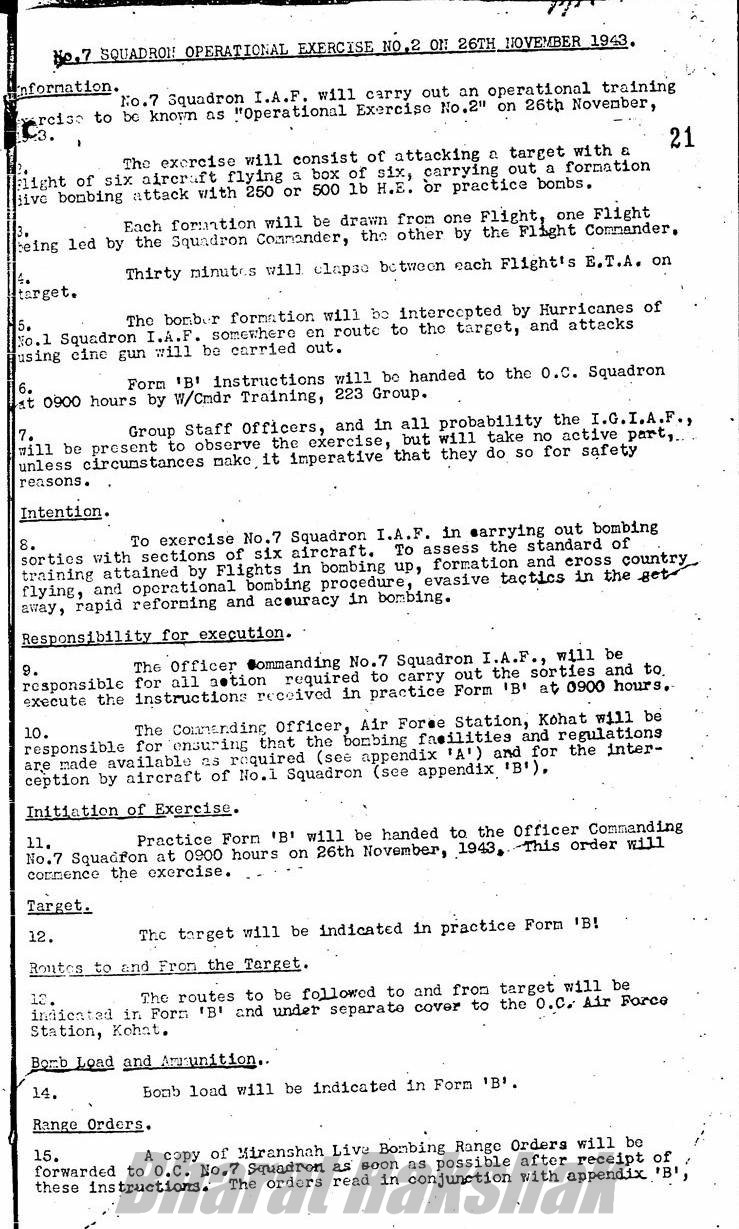

From 1st March to 8th March 1944, the close support exercises with the Army formations (which were being trained for General Wingate’s Chindit Second Expedition) were satisfactorily carried out and a letter of appreciation was given by Maj. Genl. M Stymes, Officer Commanding Headquarters Special Forces.

World War II: 7 Squadron’s First Tour.

On 10th March, 1944, the squadron commenced its move to Kumbhirgram near Silchar in Assam. The main air party consisting of 15 Vengeance aircraft and two Harvards left on the 19th. By the 22nd of March, the air party arrived at Uderbund airstrip, 12 miles from Kumbhirgram (east of Silchar).

The squadron arrived on the battlefront just as the Japanese offensive was getting into full swing. They were rapidly advancing towards Imphal. Apart from advancing from the East, the Japanese Army split up and commenced advancing towards Imphal from the North too. This was the sector (north of Imphal), that was assigned to the squadron to support in countering the advancing Japanese army.

The Squadron’s Headquarters were set-up at Kumbhirgham, near Silchar. The aircraft were based at Uderbund where a paddy field had been cleared to make an airstrip.

Only two of the squadron’s pilots, the CO Sqn Ldr. Hem Chaudhuri and Fg Offr. KL Bhatia had experience of flying operational sorties in the World War-II. All other air crew of the squadron were going to face the enemy for the very first time.

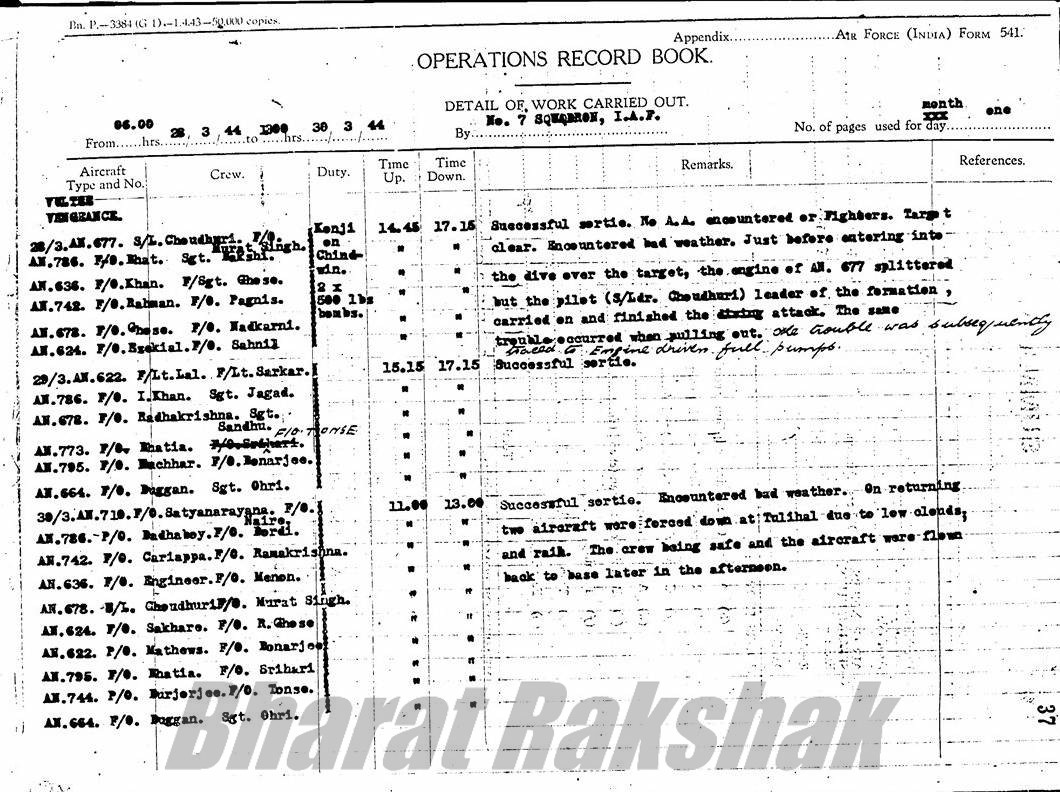

The first operational sorties from Uderbund were flown on 28th Mar 1944, when six Vengeance bombers led by Sqn Ldr. Chaudhuri attacked Kenji on the Chindwin and successfully bombed the above enemy positions.

A page from the squadron’s Operations Record Book mentioning the first Operational sortie 28th March, 1944, in this tour.

The operations continued in the month of April 44, when targets like Myothit, Japanese army encampments at Imphal, Army convoys on the Tiddim Road etc. were just a few of the umpteen number of missions flown by the squadron.

On 23rd April, the squadron’s flight was returning to base from a bombing mission when they spotted a convoy of Japanese trucks on the Tiddim road. Squadron. Ldr. Hem Chaudhuri peeled off from the formation-bomb racks empty, dived down to strafe the convoy with his four wing mounted cannons with great gusto. Damaging some and scattering the rest off the road.

The Vengeance was always considered a difficult aircraft to fly specially on take-off fully loaded, and conditions on the ground did not help either. The first fatal loss was on 1st May 1944, when Fg Offr. EH Dadabhoy was lost flying in the bad weather in a valley west of Imphal. His gunner, Fg Offr. JH Dordi was ordered to bale out of the aircraft by the pilot and was able to trek back to friendly lines over the next two days.

This incident is described in the squadron’s ORB in the following word: “In the afternoon (3rdril), Fg Offr. Dordi turned up looking surprisingly fresh and un-disturbed, in borrowed clothes and a borrowed jeep It appears that his pilot hemmed in by thick turbulent cloud in a valley west of Imphal, had made him bale out. Fg Offr. Dordi after swimming rivers, walking approximately 25 miles, and being entertained by various tribesmen had finally found the Army who brought him back. This officer was directing bombs on the Japanese the very next day”.

Fg Offr… Dadabhoy never returned and was presumed killed when he tried to land his aircraft in the same valley.

On 8th May, Fg Offr. M Latif Khan’s Vengeance crashed just after take-off. Though the gunner Sgt Ghosh was extricated out of the aircraft by Sqn Ldr. Davies, Fg Offr. Khan was found to be dead in his harness. The aircraft’s ordnance (2 x 500 lbs. bombs) exploded soon after. Flt. Sgt Ghosh had survived his third crash.

This incident has been described by an eye witness: “In May, 1944, this officer was in the vicinity when an aircraft, shortly after taking off on an operational flight, crashed and burst into flames. Sqn Ldr Davies immediately drove to the scene and observed the rear gunner collapse in an attempt to get out of the aircraft. Heedless of the danger from the ammunition which was exploding, and also aware that the aircraft carried bombs, he climbed on to the wing to extricate the rear gunner whose head and shoulders were hanging over the side of the cockpit. He had to free the latter’s harness which had become entangled in some part of the aircraft, but he finally managed to lift him out of the cockpit and drag him clear of the burning wreckage. Sqn Ldr Davies then attempted to lift the body of the pilot out of the blazing front cockpit but was unsuccessful in doing this owing to smoke and flames. He could see that the pilot had been killed in the crash. After warning all personnel of an imminent explosion he, with the assistance from another airman, carried the gunner to the sick quarters. Less than two minutes after he had left the scene; two 500lb bombs exploded completely destroying the aircraft. The timely and courageous action of Sqn Ldr Davies had saved the life of the rear gunner”.

Another causality was towards the end of May, when Fg Offr. MM Engineer was trying to formate with a group of USAAF B-25 bombers after getting lost. Mistaking him to be a Japanese Oscar, the B-25 gunners fired on the Vengeance, killing Sgt KC Ball, his rear gunner.

The squadron’s Equipment Officer, Plt. Offr. SS Bedi had his store in Kumbhirgram and since the flight was based in Uderbund, Bedi had a taxing time shuttling between both locations. One day the Flight Commander complained to Bedi about the un-availability of certain equipment and asked for Bedi’s personal attention in the matter and his immediate visit to the flight. Bedi had been particularly busy on that day and had already visited the flight a couple of times. He turned to the Flight Commander to say he was doing his best to support the flight. With a very serious face, he said, ‘No any the Operation, No any the co-operation Half the Bedi here, half the Bedi there. What the poor Bedi can do?’ From then onwards, Plt Offr. Bedi was always referred to as “Half-the-Bedi.” It was very typical of Bedi that whenever he saw an unfamiliar face, come to him for supplies, without ascertaining the requirement, his answer usually would be: “have not got it”. But, whenever anyone was in a tight corner, he would certainly come to the rescue by producing the item somehow from somewhere.

Most of the Squadron flying was done in bad weather. In 1944, the monsoon came early in those parts of the country. In the early days of April the weather was fair with small scattered cloud sand good visibility. As the weeks advanced, the air became thick with smoke for at this time of the year, the local tribes set fire to the forests to clear land for planting paddy. The smoke was so dense that it reduced visibility to a few hundred yards.

Despite the weather, In April, the Squadron flew 344 sorties, logging 620 flying hours.

What the personnel of the Squadron had seen by then by way of rains was nothing compared to what hit them on 1st May when the “Chota” Monsoon struck. By the 2nd the rains had turned the airstrip into a veritable swamp, making the airstrip absolutely unusable. Hopes rose by the afternoon of the 3rd and the flight commander Flt Lt PC Lal decided to test the runway by driving a truck across the tarmac. Unfortunately, due to the heavy slush, the truck got bogged down just outside his office, the CO Squadron. Ldr. Chaudhuri too decided to make a taxi run but, the aircraft refused to move after a few feet even with 35” of power boost. By 5th May afternoon, following a few bright sunny afternoons, the strip was considered fit enough to allow the aircraft to take-off.

However, in May, the rains came and doused the flames and the smoke disappeared. But, the pilots now had to face thick monsoon clouds, and that to the huge and dense cumulonimbus clouds which had to be avoided at all costs as almost certain death awaited the unwary pilot. Flying became dangerous as in clouds the pilots lost sight of each other and formations were broken up and targets were not visible. Yet, the pilots also had to keep in mind not to fly too low due to the hilly terrain. However, over time the pilots learned to dodge clouds without wasting much time and fuel to and from their designated target.

One of the pilots of the squadron vividly described his dive bombing sorties over Burma:

“One fine morning we were briefed by the ALO to bomb a village on the Chindwin River which served the Japanese troops as a Supply distribution point for the Imphal front. We were briefed about the enemy anti-aircraft guns and their fighters. We were given photographs of the village and the target. We were also briefed how best to locate it. The Met briefing consisted of information of the heavy cloud formations, winds etc. The ALO also informed us how to return back to India should anyone be shot down over enemy territory.

Starting up, engine check, check the guns and bomb release mechanism for one’s first sortie is exciting. You feel that you are the focus of every ones attention. You must not forget anything, make no mistake, for this is the real thing. The feeling is different from anything that can be worked up in training. While training in some secluded part of India, you know at the back of your mind that there is every possibility of meeting enemy fighters or being shot up by Ack-Ack, and the worst of all, having to try and escape from enemy territory.

But these are thoughts of a fleeting moment-your leader signals and you taxi out on to the runway to the take-off point. The leader checks the assembly of aircraft. A last look over the controls and instruments, and we take-off, one by one all twelve of us. We fly around and get into formation.

The leader sets course at the appointed time, climbing for height. The other aircraft follow faithfully. The sight of the other aircraft gives one confidence. It’s a warm comfortable feeling to have so many eyes searching the skies ready for action. I have always found that head and hands become firmer when I am flying in formation. Enemy territory becomes a place to bomb and strafe when others are there to help you, and home does not seem so far way. There is actual comfort in numbers.

The actual bombing takes but a fraction of a minute on each sortie-it is the journey to the target and back which tries one’s patience and taxes one’s nerves. On the Assam front, most of our sorties took us 150 miles from our base-that meant at least one hour’s flying over enemy territory, over mountains reaching to 10,000 ft. over densely clad jungles and often over clouds whose base was a few feet above the earth and ceiling 20,000 ft.

The weather was our principal enemy. A number of times we dodged clouds and flew through smoke, but on arriving at target found it completely obscured by clouds or smoke or both, making it impossible to dive and bomb.

The dive takes only a few seconds to perform. Those few seconds call for intense concentration from the pilot. Each nerve is tense and the body taut, for the slightest error might cost you and your air –gunner their lives. You aim your aircraft on the target in a steep dive through 6000 feet. Then you release your bombs. Once your bombs are gone you pull out of your 320 miles an hour dive. You forget enemy fighters and ack-ack and weather. Your eyes are glued on the target during the dive-nothing else worries you. After you have dropped your load of bombs you feel exhilarated, you re-join formation and make for home over hill and dale with the extra speed that the momentum of the dive has given you.

The home field is a welcome sight. It means food and drink and some lazy time in the mess. And yet, I know pilots who are eager to be-off again in a few moments after they have landed. Flying can get under ones skin, as most of us know”.

As days passed, entries about became more frequent, ‘Continuous showers of rain …………… No flying………………Airmen’s bashas collapsed like houses of cards, and the rain got into practically everything………………The Airmen had a particularly tough time.

In spite of all this the Men’s morale was high. So much so that the squadrons complaints were not with the inconveniences suffered from the Weather, but that the weather kept the Squadron grounded or rendered their sorties aborted on many occasions. This was particularly so from 28th April to 10th May, 1944, there was practically no flying due to the inclement weather.

Throughout, the weather remained treacherous with a constant cloud layer at 700’ going as high as 22000’and ‘lots of mucky stuff hanging in the valleys’. The Burmese mountain ranges run North-South and as high as 12000’, thus flying was always through valleys and on most occasions the valleys were blocked with mist or clouds. Getting through these without and navigational aids, with horizon to horizon jungles below, and landing at a slushy ‘kutcha’ airstrip was in itself quite an achievement those days.

On 13th April, 1944, 12 aircraft took-off from Uderbund at 09:12 hrs. on a ‘close-support’ mission. A hilltop near Imphal with heavy Japanese troop concentration was to be demobilized. It was a tricky target in as much as our own troops were close to the hill. The attack was however highly successful. Enemy casualties were estimated in the region of ‘300’ from the air bombing.

In spite of the continuous bad weather, during May 1944 itself, the squadron flew 353 Operational Sorties, logging 611 flying hours. Thus averaging 16 sorties a day. The famous bombing of the Manipur Bridge on 25th May 1944, was done in 10/10th (Eight Octa) cloud-as a completely overcast sky was called in those days. The difficulty in the target in this case was augmented by high hills surrounding the bridge. Seven aircraft went on this mission. A direct hit on the eastern end bridge thus, destroying it was later confirmed by the Army. This bridge was a key link to the Japanese line on communication on the Tiddim Road. In fact on 31st itself, 34 Operational Sorties were flown with all aircraft getting a crack at the enemy. Their strategic targets ranged from Myothit, Thungdut, Kawya, Lepantho, numerous villages, supply dumps and camps in the Chindwin River, Imphal, Kalewa and Fort White areas. They dive bombed the Tiddim and Kohima roads causing huge landslides thus blocking these roads and delaying the enemy supply columns, vital to them. The landslides also caused big traffic holdups, and making them sitting ducks for the strafing Hurricanes.

The rest of operations involved Dive Bombing missions on numerous sorties on Maungdaw and Razabil, with the Vengeance being the ideal weapon of war against the targets in the mountains and thick jungles.

With the onset of the ‘real’ monsoon during the last week of May, 1944, the work of the Vengeances on the Burma front seemed to have come to an end. With thick clouds in the sky, bombing had to be done in shallow dives. This could however, be more effectively done by level bombing using the light and medium bombers – Hurricanes and the B-25 Mitchells.,

On 1st June, the squadron made two attempt to bomb the remaining of the two Manipur bridges. An entry in the Squadron’s Operations Record Book for the day reads as follows:

“The boys were up early this morning for in interesting target had come through. The serviceable of the two bridges across the Manipur River had to be pranged. Unfortunately, to the keen disappointment of the boys, the weather proved other than favourable. Thick clouds and poor visibility, forced the formation back to the base. In the afternoon, another attempt at the same target was made. The formation of 12 aircraft, meeting with thick Cumulonimbus clouds of great vertical extent, headed south and at about 70 miles from the base turned east,

In order to avoid them. Forty miles on this easterly heading, finding no improvement in the weather, the formation returned to base”.

Sqn. Ldr AB Awan took over ‘Nominal’ command of No. 7 Squadron on 6th June, 1944, while Squadron. Ldr Hem Chaudhuri remained in command of ‘Operations’.

On the 11th, two attempts were made on the bridge both led by Flt Lt. PC Lal. This time they made it to the bridge, but a massively thick cloud up to 10000’ height made the dive bombing impossible. The aircraft returned to base with their bomb loads.

The squadron’s first tour came to an end on 11th June after the aborted missions mentioned above. The squadron were given barely 24 hours’ notice to move out from the Burma front. On 12th June the squadron began their move to a peace station at Ranchi. Sqn. Ldr. Hem Chaudhuri was posted out from the Squadron. Command of the unit passed onto Sqn Ldr. AB Awan.

Hi,

Aside from P.C. Lal’s ‘My Years With The IAF’, is there any other book that covers the Indian Air Force operations in WW 2?

And thank you for all the effort on this website — I enjoy it very much.

Cheers,

AW

KS Nair’s “Forgotten Few”, S Sapru’s “Combat Lore” are two

Thank you

Thank you