The use of air power by any nation to achieve military objectives is a significant step with international ramifications. While the IAF was employed in the offensive role during 1948 in Jammu & Kashmir, it was not utilised offensively during the operations against intruding Chinese forces in 1962, which would have significantly and decisively altered the outcome of that sorry debacle. In subsequent operations during the Indo-Pak wars of 1965 and 1971, the profound effects of the judicious use of air power was exhibited repeatedly, whether at Chamb in 1965 or Longewala during 1971.

The induction of the IAF in the Kargil conflict on 26 May this year was intended to achieve the national objective of throwing out the Pakistani regular forces and other armed intruders across the LOC. The IAF was thus drawn into this battle fought over some of the highest terrain on earth. Never before has any air force been tasked to achieve such military objectives; not to mince words, therefore, this operation by the IAF is, by professional standards, a trailblazer. The types of targets required to be engaged were not conventional target systems that air forces all over are trained to engage. No mobile forces or armored columns, neither industrial targets, nor power plants or railway yards here. No runways to neutralise, or communication networks to paralyse. The targets were simply intruders, lightly burdened individuals well trained in the art of mountain warfare, well motivated and mobile. They were familiar with high altitude operations and were firmly ensconced on the many vital heights in the area. No traditional command posts or well – marked logistics supply lines (the common targets of air power) existed. The intruders were near invisible humans well dug-in into hideouts with well stocked stores in a well planned operation which preceded their occupation of positions on various hilltops and slopes. Only their tents and earth – work structures were identifiable and these too, barely so from the air. The ubiquitous black and white colour combination of the terrain broke up outlines and provided natural camouflage, to the extent that one could look at a photograph for minutes before realising that one was looking at a bunker!

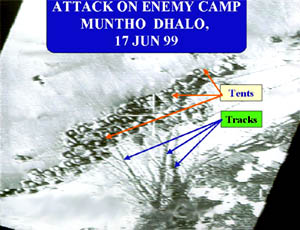

Frequent snow-falls effectively shrouded stores and supplies under a uniform white blanket. It is a significant fact that the biggest target engaged during Op Safedsagar (as the air operations in the Kargil area were called) the supply camp at Muntho Dhalo, would normally have been the smallest target considered for the use of air power during a normal all-out war! Lucrative targets were available only on the other side of the Line of Control (LoC), which was an area that the air force scrupulously avoided, as per the mandate given them by the Government. Such targets simply do not commend themselves to many types of armament and weapon delivery systems on the inventory of any air force. The IAF therefore selected targets with the intention of inflicting as much damage on personnel and weapons as on supplies. Such relentless attacks effectively reduced the enemy’s will and capacity to fight. The attacks were followed up by army assaults to clear the area. The targets were widely dispersed and in many pockets all over the region, besides being very mobile; this necessitated practically individual attacks. Stores, once located, were effectively engaged but the effects of the enemy’s losses, obviously, were felt only over a period of time.

The IAF was first approached to provide air support on 11 May 99 with the use of helicopters. This was followed by a ‘go ahead’ given on 25 May by the Cabinet Committee on Security to the IAF to mount attacks on the infiltrators without crossing the LoC. While there was considerable pressure from outside the IAF to operate only attack helicopters, the Chief of Air Staff succeeded in convincing the Govt. that in order to create a suitable environment for the helicopters, fighter action was required.

Effect of Environment

The severe degradation of aircraft and weapon performance is difficult to completely appreciate. No aircraft has yet been designed to operate in a Kargil-like environment. At high altitudes, a crucial factor in aircraft performance is the reserve of power available, which, for the MiG and Mirage fleets, was a strong point in their favor. In comparison, the Fairchild A-10, widely quoted as being the ideal platform, would have been a misfit. It is widely (and incorrectly) stated that using Mach 2 aircraft would not produce results; however, a Mach 2 capability does not necessarily imply an inability to operate at lower speeds; further, all air-to-ground attack speeds are approximately the same (750-950 km/h) for fixed-wing aircraft.

Due to the very different attributes of the atmosphere at that altitude, even weapons do not perform as per sea-level specifications. Variations in air temperature and density, altering drag indices and a host of other factors (which have never been calculated by any manufacturer for this type of altitude) cause weapons to go off their mark; for the same reasons, normally reliable computerised weapon aiming devices give inaccurate results.

In the plains, a 1000-pounder bomb landing 25 yards away from the target would still severely disable, if not flatten, it. In the mountains, however, a miss of a few yards would be as good as the proverbial mile, due to the undulating terrain and masking effects. In addition, due to the variation in elevation the “miss” would be greatly magnified in the linear dimension, further exaggerating the “inaccuracy” of the weapon/delivery. While this would lead to apparent inaccuracies in weapon delivery, there is, paradoxically, a need for pinpoint accuracy in conditions where that very attribute is severely degraded by the factors mentioned above.

The First Few Days

The loss of one fighter and one Mi-17 chopper to enemy action indicated the need for a change of tactics, resulting in withdrawal of armed helicopters and employment of fighters in modified profiles out of the Stinger SAM envelope. By itself, the change of tactics is nothing unusual, and is an inherent part of the qualities of flexibility and adaptability; in fact, a far more serious lapse would be a dogged tendency to persist in sacrificing assets when, clearly, there was a need for a re-assessment. It is, perhaps for this reason that NATO, after deploying 100 Apache attack helicopters in Greece, reconsidered bringing them into Kosovo till the shooting was over, as they felt the environment didn’t justify it. Unfortunately, IAF Mi-25/35 attack helicopters were not able to operate in this terrain.

|

A personal message is readied by the ground crew of No. 9 Wolfpacks Squadron for delivery by a MiG-27ML. (Copyright : Outlook) |

One of the many facts that have emerged clearly is that target acquisition by the pilot is the bottom line. Totally unfamiliar surroundings in the Kargil area made target recognition difficult from the ground, let alone from a fast moving aircraft. As a result, the initial few sorties from high levels were not effective as desired. However, once revised and modified profiles, tactics and manner of system usage had been perfected, the accuracy of the air strikes improved dramatically. Any time the target was spotted, a very high success rate invariably resulted.

Air Reconnaissance & Battle Damage Assessment: Crucial Aspects Of An Air War

The popular picture one normally associates with air strikes brings to mind helmeted pilots starting up their aircraft, flying to the target in the teeth of intense anti-aircraft fire and battling their way through hordes of enemy fighters to press home their attacks despite superhuman odds. In all fairness, that’s the way it actually happened until the Second World War – the famous 1000 bomber raids over Germany, with the US 8th Air Force flying by day and the RAF by night, at a terrible cost in lives and machines.

Even at that time, though, the “back-room boys”, that anonymous bunch of faceless experts who lived their lives poring over reconnaissance (recce) photographs, noting detail after painstaking detail, provided the target information that ultimately formed the basis of the bombing missions. Without such analysis a strike aircraft would have been like a lethal boxer in the ring – blindfolded!

Three Main Steps in Neutralising a Target

Far from being an off-the-cuff quick reaction affair, each air strike is the end result of a carefully planned chain of events spanning several areas of specialisation. Broadly speaking, an air strike would have the following components:-

(a) Recce mission(s).

(b) Air strike mission(s).

(c) Battle Damage Assessment (BDA) mission(s).

(d) If so dictated by results of BDA, or by follow-up recce, repeated air strikes.

Effective recce regularly pre-empted the enemy’s attempt to continue operations from an earlier target; a good example is the enemy supply camp near Pt 4388, in the Dras sector, attacked earlier by four Mirages dropping 24 high explosive 1000 lb bombs (amounting to 12 tons of high explosive churning up a restricted area)! This was followed by an equally heavy air strike against this camp the next day. The weight of attack put into these air strikes were formidable, and greatly influenced the conduct of the ground operations.

Photography in the Optical Wavelength. This can be done by cameras which point either vertically down, or sideways at a variable angle. While the sideways looking cameras possess the obvious advantage of staying on one’s own side of the LOC/border while “peeking” into the enemy’s territory, it has other implications like the variation of scale with distance from the platform, definition at extreme ranges etc, which create complications during subsequent interpretation of the film. The IAF uses MiG-25s, Canberras and Jaguars for optical photography from medium /high altitude. Satellites can also be used, but the IRS series do not provide the resolution required for the kind of information wanted during Op Safedsagar, namely, location of enemy bunkers, tents/camps and tracks/paths. Satellites do exist, however, with this capability, which would demand a resolution of less than a meter. Optical photography can also be done from low level as demonstrated by MiG-27s during the annual Ex Vayu Shakti (live firepower demonstration) using the Vicon equipment.

Infra- red (IR) and other Wavelengths. Platforms can also carry sensors to detect IR signatures – some sensors can detect IR signatures of aircraft types about 10-15 minutes after they have taxied out from the tarmac!

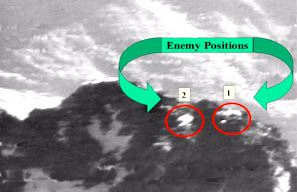

Interpreting the Result. This is the bottom line – its all in the interpretation. A skill acquired through a specialised photo-Interpretation Course, the Photo Interpreter (PI) is a very scarce, and an extremely valuable commodity. There is a great demand on his skills. After the recce aircraft scans the stipulated sector in a number of swaths, these photographs are then fitted together to form “mosaics” of closely integrated photographs which are related to a large scale map. The PI then goes through each and every feature of the photograph – in this process, skill and “gut feeling” also play a major role, as especially in mountainous terrain like during the Kargil Ops. For example, if a group of tents is found, a pattern of tracks would logically emanate from it leading on to bunkers and ground positions; the reverse would also be true.

A Coordinated Air Campaign

An air war is a complicated business, requiring the coordination of different types of missions. The exact proportion or mix would change with the situation. While it is an acknowledged fact that the IAF operated largely in an environment of air superiority as far as air opposition was concerned, the large proportion of air defence missions, perhaps, played a significant part in bringing this about. Air Defence missions included escorts which flew along with every strike force as well as air superiority fighters that operated independently to ensure that the specified portion of airspace was sanitised for the specific time period, both by day as well as by night.

As of 12 Jul 99, IAF fighters had flown approximately 580 strike missions, supported by around 460 Air Defence missions like Combat Air Patrol and escorts and about 160 reconnaissance sorties, amounting to a total of approximately 1200 sorties. Helicopters accounted for a total of approximately 2,500 sorties transporting more than 800 troops, almost 600 casualties and close to 300 tons of load besides flying scores of operational missions like strikes. Added to this were many sorties by the IAF transport fleet, bringing in supplies and troops and evacuating men and material from the forward airbases near the war zone.

The Increasing Effects of Air Strikes

As a result of the IAF’s air strikes, severe damage to enemy personnel and equipment became apparent in various areas. It is surmised that air strikes contributed to a significant portion of the enemy’s casualty list, as apparent in the numbers. However, the most telling effects on the ground were from intercepts of enemy radio revealing severe shortage of rations, water, medicines and ammunition. Losses due to air strikes and inability to evacuate their casualties were also mentioned in the intercepts. This was the actual manifestation on the ground of the result of effective air strikes by the IAF. The effect of accurate attacks is best summed up by a message received from one of the HQ of the Indian Army:

“You guys have done a wonderful job. Your Mirage boys with their precision laser guided bombs targeted an enemy Battalion HQ in Tiger Hill area with tremendous success. Five Pakistani officers reported killed in that attack and their Command and Control broke down – as a result of which our troops have literally walked over the entire Tiger Hills area. The enemy is on the run. They are on the run in other sectors also. At this rate the end of the conflict may come soon.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

IAF Air Strikes: The Results

The IAF has always approached its targeting solutions espousing the concept of target systems, rather than targets in isolation. This concept proved its worth during the operations; for example, the Tiger Hill target system consisted of four components:-

(a) Enemy HQ on top of Tiger Hill

(b) Scattered enemy positions on the hill feature.

(b) Enemy supply camp approximately 2.5 km west of Tiger Hill.

(c) Another enemy camp to the North near the LOC, forming a link to areas beyond the LOC.

Systematic engagement of three of these components (the scattered enemy positions on the hill were ignored) in a planned manner was directly responsible for the fall of Tiger Hill. In general, IAF air strikes against enemy supply camps and other targets yielded rich dividends. A noteworthy fact is that there was not a single operation on ground that was not preceded by air strikes, each and every one of which was the result of coordinated planning between 15 Corps and the AOC, J&K. However, one of the valuable lessons that emerged was the need for joint Army-Air Force planning and consultations from the very beginning, where the Air Force would be able to contribute by rendering advice on targeting which could, at the very outset, be incorporated into the Army plan of ground operations. This would prove far more effective than a case where the Army proceeded as per its own plans made earlier in isolation, and called for air support when they felt it was required or ran into difficulty. Some of the more glaring lessons which emerged from Operation Safedsagar are discussed below.

|

An Airman checks a 500- pounder fixed to a MiG-27ML at Srinagar AFS. (Picture : India Today) |

Firstly, in the area of interdiction of enemy supplies, the successful and incessant attacks on the enemy’s logistic machine had, over the last few weeks, culminated in a serious degradation of the enemy’s ability to sustain himself in an increasing number of areas. The series of attacks against Pt 4388 in the Dras sector was an excellent example of how lethal air strikes combined with timely reconnaissance detected the enemy plans to shift to alternate supply routes which were once again effectively attacked. In this the IAF succeeded in strangling the enemy supply arteries, amply testified to by enemy radio intercepts. The primacy of interdiction targets as opposed to Battlefield Air Strikes (BAS) targets was clearly brought out, as also the fact that air power is not to be frittered away on insignificant targets like machine gun posts and trenches, but on large targets of consequence (like the supply camp at Muntho Dhalo or the enemy Battalion HQ on top of Tiger Hill). Gone are the days of fighters screaming in at deck level, acting as a piece of extended artillery. The air defence environment of today’s battlefield just does not permit such employment of airpower anymore, a significant fact that needs to be understood by soldier and civilian alike.

|

|

|

A sequence (clockwise from top left corner) showing the Pakistani supply camp at Muntho Dhalo under attack. The last frame (top) shows the camp after the attack. |

|

The second major impact of air power in this operation was in the area of casualties. Normally, an enemy defending a well fortified position (in this case, Pakistan) would suffer between 3-6 times less casualties than does the force on the offensive. However, this operation has seen the reverse, with the enemy casualties far in excess of those suffered by us. One significant fact must not be lost sight of; of the two warring sides, it is the Pakistani Army that suffered air strikes, which, obviously, contributed significantly to its casualties. It is felt that without the use of air power, our own casualties could have approached if not exceeded four figures.

The third aspect is that of attack chopper operations. IAF dedicated attack choppers like the Mi-35 were incapable of operating at that altitude, which prompted the use of armed and modified Mi-17s for the role. Besides the capability of the machine itself vis-à-vis the area of operation, the creation of the right air defence environment is a crucial factor which would determine the employment of this platform. Effectiveness versus vulnerability would need to be examined; during Op Safedsagar, the abundance of man portable SAMs in all enemy-held areas precluded the effective employment of attack choppers. As a result, whether Army or IAF, choppers were constrained to operate in SAM-free areas. Nevertheless, IAF Cheetahs were instrumental in carrying out front line roles like providing a platform for the Airborne Forward Air Controller (FAC), a fighter pilot who guides the fighters in to the attack against ground targets.

The fourth major impact of air power is in the enormous difference it made to the ground operations, no better example of which exists than the message from the HQ of a field Army unit, (shown in italics above) stating that “as a result of the precision air strikes on Tiger Hills our troops have literally walked over the entire Tiger Hills area. The enemy is on the run..”

Fifthly, night operations were carried out using ingenuity and imagination; at times, excellent results were achieved by aircraft like MiG-21s using little else but a stop watch and a GPS receiver. These operations had a significant effect on the enemy’s resilience, stamina and very will to fight.

Sixthly, the effort put into air defence escorts and area Combat Air Patrolling by day as well as night proved an effective deterrent which ensured total air superiority. At times, PAF F-16s orbited a scant 15 km (on their own side of the LOC) from our strike formations attacking Pakistani targets, kept at bay by our own air defence fighters flying a protective pattern above the strike.

The seventh aspect is the high degree of imagination, flexibility and IAF-Army coordination which marked every phase of the operation.

The eighth aspect concerns attrition and its present day acceptability. During all out wars, the attrition rate that would have been accepted even a decade ago would not be acceptable today. Political nuances and public pressure, together with the shrinking of time frames and greater visibility due to strides in technology, have greatly lowered the acceptable threshold of attrition in an air war.

In the final analysis, the effective application of air power has indisputably saved further casualties as well as compressed considerably the timeframe in which our Army has made such progress on the ground. In this context, the basic functions of air power have been repeated, though on a much larger scale, when compared to the IAF’s operations in this area during 1947-48, when IAF Tempests carried out strafing and rocket attacks on the intruders and Dakotas ferried in as well as Para dropped troops and supplies. As then and now, when called upon by the nation the IAF has joined as an equal partner to the Army to meet the national objective.

Conclusion

One of the first conclusions that any analysis of the air operations during the Kargil Operations would come to is that Operation Safedsagar saw the employment of air power in totally unconventional ways. Because the operating environment was so different from any environment encountered before in the history of military aviation, formerly accepted doctrines and tactics on the employment of airpower had to be thrown out of the window and brainstorming resorted to in order to arrive at newer, more effective methods of air warfare.

This new operating environment prompted the need to redefine operating paradigms of the use of air power. It was not a question of modifying a tactic or two, but of evolving a totally new philosophy of operation to meet the stringent and largely unfamiliar set of limitations which emerged in almost every area of air operation. This required a large amount of flexibility of thought as well as procedures, as the bottom line was innovation and ingenuity.

Almost from the very beginning of the operations, IAF intellects were busy ticking over in a near constant brain-storming session aimed at deriving lessons from Operation Safedsagar. Being an ongoing process, the immense experience gained from this operation would stand in good stead in the times to come. These lessons would be applicable to all the world’s Air Forces, for it is the first time in the history of military aviation that such an air operation took place in such an environment. While conventional long-accepted air power theories no longer held good, a new set of operating paradigms had to be evolved almost overnight to cope with the situation.

This is the first time the IAF fought a limited war, hitherto thought to be an unlikely eventuality, as air power and escalation to an all-out war were thought to be synonymous. The deterrent effect of air power has been enhanced by this fact, as the prospect of decisive air action is now a proven possibility in even a LIC (low intensity conflict) situation.

Operation Safedsagar was, therefore, a turning point in the history of military aviation, and an operation that will, no doubt, be discussed and dissected for the next few years.