The story of No.12 Squadron’s effort to save Poonch, including the effort to airlift the 25 pounder guns into a beseiged garrison.

It should have been a Mosquito light bomber squadron. Formed on 1 December 1945, as a Spitfire squadron at Kohat, No.12 Sqn of the Royal Indian Air Force converted to the Airspeed Oxford in Bhopal but within months was to become the first Transport squadron of the RIAF. It drew its pilots from the existing fighter squadrons, most of them having flown Spitfires, Hurricanes and Harvards. An Air Marshal recalls, “We were given our training on the twin-engined Oxford and we were to go on to the Mosquito. But the Mosquito was an aircraft which had a fuselage made of plywood! Well, not quite basic plywood, but something like that. Amazingly, Mosquitos gave great service in Europe but here, in the topics, they fell apart! Moisture and heat!”

With the induction of Mosquito being shelved, but with the pilots already having done part of the twin-engined training, it was decided that a Dakota squadron would be formed instead. From Bhopal, the squadron was shifted to Mauripur in Karachi, an existing RAF airfield which is a major PAF base today. Recalls Air Marshal L.S. Grewal, at that time a Flying Officer with No.12 Sqn, “Training on the Dakotas began, but that was still underway when partition (of the country) came about. Just half a dozen pilots were fully operational, while most of us were only trained for daytime flying. The squadron was on the move to Chaklala and Risalpur, some of us were still at Karachi, when a few days before partition, it was decided that the Dakota squadron would move to Agra. We had six aircraft and half a dozen reasonably trained pilots who each had about 30- 40 hours on the Dak, while people like me had just 15- 20 hours, all of which was by day.” It was Shivdev Singh (now a retired Air Marshal) who was commanding this ‘hotch-potch of a squadron’ in late August 1947.

Within the next two months, the situation in J&K became alarming. While Maharaja Hari Singh dilly–dallied and Kashmir’s fate seemed to hang fire, plans for annexing the state by Pakistan were beginning to take shape. In an interview published in “Defence Journal” (Karachi, June-July 1985) with Maj. Gen. Mohammad Akbar Khan (code named “General Tariq”, who was the commander of the raider forces), he goes on record to say, “A few weeks after partition, I was asked by Mian Iftikharuddin on behalf of Liaquat Ali Khan (Prime Minister of Pakistan) to prepare a plan for action in Kashmir.”

On the 24th October 1947, a tribal lashkar attacked Muzaffarabad and successfully captured it. The next day they advanced and captured Uri. On the 26th, they occupied Baramula and Maharaja Hari Singh fled from Srinagar to Jammu where he finally acceded the State to India. Says Air Marshal Grewal, “When Pakistan used the raiders as an excuse to attack, the situation developed very fast. On the 26th afternoon we were asked to move to Delhi. We had four Dakotas with us and at the briefing in Air Headquarters, there being no Group at that time, we were told that the situation was critical, and we were to fly one of the Army units…1st Sikh…with one company to Srinagar airfield.”

The airlift began early morning on October 27th and the first troops to land at Srinagar were the Sikhs, who were built up to two companies by nightfall. The landing was unopposed as ‘Tariq’s Raiders’ held themselves up at Baramula indulging in an orgy of rape and plunder. It is interesting to read about General Tariq’s version of what happened, “It was a part of their (tribal lashkars) agreement with Major Khurshid Anwar of the Muslim League National Guards, who was their leader, that they would loot only non-Muslims.” He adds, “In September 1947, when the Prime Minister launched the movement of the Kashmir struggle, Khurshid Anwar was appointed commander of the Northern Sector. Khurshid Anwar then went to Peshawar and with the apparent help of Khan Qayyum Khan raised the lashkar which assembled at Abottabad and with which he entered Muzzaffarabad on the 24th of October 1947-reached Baramula where he delayed the lashkar for two days for some unknown reason.”

Air Marshal Grewal adds, “The situation was so bad that we were instructed to fly low over the airfield first and see what was happening before attempting to land. Luckily, the raiders were still at Baramula enjoying themselves and hadn’t arrived.” The total number of Dakotas available on October 27th were listed in an Operational Order issued to 1 Sikh. Flight A from Willingdon, due to take off at 0500 hrs, included 6 civil Dakotas (to transport a company of 1 Sikh). Simultaneously, Flight B from Palam would also leave at 0500 hrs, comprising 3 RIAF Dakotas (ferrying the battalion’s Tac HQ). Flight C from Palam was scheduled for 1100 hrs comprising 8 Dakotas (Patiala Mountain Battery) while Flight D also from Palam would follow at 1300 hrs comprising 11 Dakotas (second company of 1 Sikh). The civil Dakotas were to carry 15 men plus 500 lbs while the RIAF Dakotas had a capacity of 17 men along with the additional 500 lbs. ‘Men’ included personal arms, equipment and bedrolls.

The gloves were off once the first few Dakotas touched down at Srinagar airfield. No.12 Squadron RIAF along with the hastily commandeered civil Dakotas, were to fly a series of shuttles between Delhi and Srinagar, airlifting the entire 161 Infantry Brigade within the next five days. Flying Officer (later Wing Commander) Desmond Pushong records a typical day in his log book: On October 30, flying a Dakota III, (VP 901), along with a crew comprising Flying Officers Gill and Roy and Warrant Officer Biswas, they took off from Palam to refuel at Amritsar prior to landing at Srinagar, a total flying time of 3 hours and 10 minutes.

Says Pushong, “The civil Dakotas were slightly faster than ours because their engines were fitted with ‘needle’ props and the fuselages were highly polished being in natural metal. Our aircraft sported dull camouflage paint that slowed us down a bit.” The same aircraft and crew returned to Ambala at night, via Srinagar, in 2 hours and 15 minutes.

1 Sikh was commanded by Lt. Col. Dewan Raniit Rai, who decided to push his battalion right up to Baramula rather than deploy around the Srinagar airfield itself. This gallant officer was killed the next day, but his action was the first of many to cheek the advance of the tribal lashkars. The situation on the ground was desperate and as Air Marshal Grewal further recalls, “On the second or third day, we started using our fighter aircraft. They operated out of Ambala, strafing on the Baramula-Srinagar road, trying to stop those people from coming in. There was one bridge at Shalateng…we called it the black bridge…and the raiders in fact, had came up to that point. Our intention was to get the Spitfires to operate from Srinagar, so one of the Dakotas went to Ambala to pick up the technicians and basic equipment, ammunition, etc. That aircraft was obviously overloaded, our knowledge of the Dakotas performance being so little in those days. Flt. Lt. C.J. Mendoza was the Captain. He never got to Srinagar and we never knew what happened to his Dakota at that stage. They possibly missed the Banihal Valley, turned right and crashed into a hill near the Sheshnag lake. This aircraft was located some 8 months later.”

The initial days at Srinagar Airfield – a civilian bus embarks troops as a civilian Dakota in the background gets ready to take on civilian refugees for the return flight.

A series of ‘lucky’ coincidences continued to aid the Indians. First, there had been the raider’s self imposed two-day delay at Baramula, followed by the unopposed landings at Srinagar and then Lt. Col. Rai’s decision to move 1 Sikh up to Baramula. The battle fought at Shalateng on 7 November was to prove decisive in that the raider column was completely routed by 161 Brigade aided by RIAF Tempests and a troop of armoured cars from 7th Cavalry. With the raiders failing over each other to get out of the way of the now advancing Indian brigade, first Baramula and then Uri were liberated. Also, the successful Shalateng Battle ensured that Srinagar itself would never again be directly threatened throughout the year-long fighting that was to follow and that attention could now be focused onto the area outside the Jhelum Valley where Kotli was reporting exhaustion of ammunition, Jhangar was beseiged, Naushera threatened, Rajouri captured and Poonch flooded by a stream of refugees while Kashmir state troops evacuated Rawalkot.

The emphasis shifted completely to the Jammu Province and Poonch in particular by the second week of November. Meanwhile, according to General ‘Tariq’: “We overwhelmed the garrison at Bagh and took control of the tehsil. We sent a lashkar to surround and isolate Poonch from Srinagar. We captured Kotli, Mirpur, Beri Pattan and the whole area both sides of the road between Jammu and Poonch…”

On November 12th, Mehar Chand Mahajan, the former Prime Minister of J&K, had appealed to the Defence Minister of India, Sardar Baldev Singh, to come to the rescue of Jammu Province. Another day was to pass before the recapture of Uri and only then could the diversion of troops and aircraft from the Valley be made possible. However by then, the fate of Mirpur had been sealed.

On November 14th, the Defence Committee of the Cabinet (DCC) met and in its appreciation of the situation, decided to evacuate the beleaguered garrisons close to the Jammu-Poonch-Uri road. Gen. Roy Bucher was confident that the Indian Army would be able to achieve these limited tasks along with the securing of the Jhelum Valley, but nothing beyond that. A study of the map of Kashmir and Pakistan clearly showed that, with the complicity of the Pakistan government, the tribal lashkars could motor right up to the Poonch border. In addition, at least forty serving soldiers who lived in Poonch had deserted to Pakistan with their arms and there were 2000 other soldiers known to be serving in the Pakistan Army who were recruited from that area. There was every possibility of mass desertion on their part to join the raiders concentrating opposite Poonch.

There were other problems as well. In the Valley, Gen. Tariq had let the raiders fight like regular troops, which in turn provided the Indian Army and the RIAF a tangible target which was soundly thrashed. However, in mountainous terrain, the tribesman was certainly going to play his own guerrilla game of infiltration, eschewing open country. The tribesman was far more dangerous, and that much more difficult to deal with, along the long and vulnerable line of communication from Pathankot to Jhangar.

In addition, the overall military situation in India was also creating its own problems. Although it seemed improbable, at that time, that the Pakistan Govt. had the stomach for an all-out war with India, intelligence gathered from various sources indicated the possibility of raids into East Punjab from Bahawaipur and pans of Rajasthan as Well as Kathiawar from Sind, by hordes of tribesmen ostensibly acting independently and out of the Pakistan government’s control. Finally, there was the major problem of Hyderabad (Deccan). The situation was fast deteriorating and it was clear that a show of military strength in that region was inevitable to subdue the Nizam’s ambitions.

On November 16th, Maj. Gen Kalwant Singh, GOC J&K Div ordered the immediate relief of Naushera, Jhangar, Kotli, Mirpur and Poonch. The Poonch link-up plan meant that the thrust of 161 Bde from Srinagar would be diverted from Uri to Poonch over the Haji Pir pass while 50 Para Bde was to fight its way from the south along the Jammu-Akhnur-Bed Pattan-Naushera-Jhangar-Kotli-Mirpur axis. General Roy Bucher, C-in-C, considered the plan to far exceed the Army’s resources and was thus ‘dangerous, fool-hardy and risky’ while Brigadier Paranjape of 50 Para Bde also voiced his reservations.

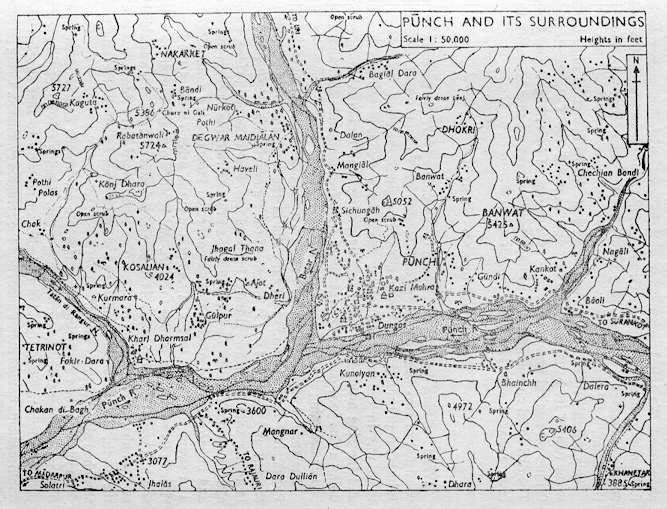

Click on the graphic to view the large map of Poonch area and surroundings

The Poonch ‘link-up’ plan proved itself to be too ambitious. The advance got bogged down in the south while the Uri column was delayed, eventually starting on November 20th. Its rearguard was badly mauled near milestone 7 where 24 lorries were ambushed. An ironical misfortune awaited the main body of troops. The state troops, seeing the lights of the approaching convoy, burnt down the wooden bridge over the Betar Nulla at Kahuta, leaving 1 (Para) Kumaon to make its own way to Poonch and becoming part of the garrison under command of Brigadier Pritam Singh. 161 Bde made its tedious way back to Uri where it was to fight many attacks in the months to come.

The Dakotas of No.12 Squadron RIAF were ordered to concentrate at Jammu. On November 16th, Pushong along with Fg Offrs Singh, Roy and WO Ghosh dropped supplies over Kotli. Entries in the log book for November 17th, record two successive flights Jammu-Amritsar-Jammu, before yet another supply drop over Kotli followed by Mirpur. A bullet fired by a rifle hit WO Ghosh in the arm over Mirpur. Says Pushong, “He got hit and when we landed back at Jammu, I took him to the doctor. But the next day he flew a sortie with me to Srinagar, followed by a supply drop mission over Poonch where a big problem had developed. This is a small place…a satellite state within J&K where a lot of refugees had congregated from across the border. Anyway, later that day we were back at Agra and Ghosh was taken care of.”

Recollects Air Marshal Grewal, “We did move our troops into Poonch but soon after they were totally cut off as Pakistan had completely surrounded the valley from all sides and the only way in was by air. There was no airfield as such though there was a small level place available where horses used to be exercised. On one side there was the river, with a steep drop of a hundred odd-feet, while on the other there was a hut. The total length of the field was some 600 yards. Landing an aircraft there under any circumstances would have been very difficult but at that time we had an extremely capable leader….Air Commodore Mehar Singh. But for him, I think that the operations would have been quite impossible for the Air Force.”

No.12 Sqn RIAF had by then come under the operational command of No.1 Operational Group with its headquarters at Jammu. ‘Baba’ Mehar Singh, a man larger than life, setting an example in almost everything he did, commanded the loyalty of the pilots in a manner that few man could ever hope for. On the other hand, another man was getting about the task of preparing the ground for the Dakotas to fly in. Brigadier Pritam Singh was ‘a tough guy’, and one who was to display remarkable courage and determination in the days to come. To facilitate a regular flow of supplies, not only for the Poonch Brigade but also for the 10,000 locals and 35,000 refugees, Brigadier Pritam Singh organised hundreds of refugees to construct an improvised airstrip.

The aircrew room of No.12 Squadron during Pandit Nehru’s visit. Air Commodore Mehar Singh is on the left. To his left, in a Peak Cap, is Squadron Leader Desmond Pushong. (Incorrect Image and Caption – The image was subsequently dated to be from 1946 and at Kohat)

Pritam Singh and Mehar Singh were symbolic of the determination and courage of the the armed forces which had to coordinate to save Poonch. Prime Minister Nehru had declared that Poonch would be saved ‘at all costs’. Kotli had already been relieved by Indian troops advancing from the south, but the advance was also temporarily halted at that stage. Around Poonch, the Indian pickets were well sited to meet the threat of the raiders from all sides. Based at Jammu, RIAF Tempest fighter-bombers and Harvards attacked enemy positions. On December 4th, Tempests subjected enemy positions north-east and north-west of Poonch to 20mm cannon fire and again on December 7th, enemy positions in the immediate vicinity of Poonch were subjected to rocket attack and strafing.

On December 8th, a Dakota successfully dropped supplies and an improvised aircraft bombed enemy targets north of Poonch while on December 9th, supplies of ammunition were dropped. Recalls Air Marshal Grewal. “At night the raiders used to move their convoys around freely because during the day Tempests would harass them repeatedly, inflicting heavy losses. Mehar Singh then had this bright idea…why not load a bomb into the cargo compartment of a Dakota aircraft and roll it out of the door. So we began to do just that, live-fusing in the aircraft with a torch and rolling it out the bomb could land anywhere within the radius of half a mile. but it created a big bang…and the man on the ground did not know where it was going to land either.”

Civilians await evacuation at the makeshift airstrip at Poonch.

It took the refugees, toiling under hostile mortar fire, six days to complete the Poonch landing strip, with fighters providing cover overhead. According to Desmond Pushong’s log book, he first flew into Poonch, from Jammu, in a Harvard with Flying Officer Choudhry on December 10th. Says he, “I went to take a look and familiarise myself with the terrain. Two days later, Mehar Singh landed the Harvard there also and followed that with a Dakota landing. At Jammu he told us that it was a difficult task but it could be done. All of us were very keen to get going and I landed there for the first time on December 12th.” Pushong’s crew consisted of Fg Offrs Menon, Roy and WO Nanu, flying the Dakota II (VP 903). It was soon to become a familiar aircraft for the Poonch garrison, Yet another Dakota was hit while air dropping ammunition but managed to land safely at Poonch.

On December 13th, VP 903 landed at Poonch on three occasions during the day. But it was premature for the Indians to celebrate. The raiders moved up field guns and by the evening had the airfield bracketed by mortars and field artillery. Recalls Wg. Cdr. Pushong, “After having got there in the first place, there was now this new crisis. I was at the bar in the mess when Mehar Singh walked in and he called Grewal and me aside. He asked the two of us if we were willing to fly there again with these howitzers and land at Poonch at night without any lights. I said we could try. His only brief to us was that if we found ourselves overshooting the runway, we were to retract our undercarriage! Anyway, Grewal said we would get the guns there but he joked that the squadron might be minus two Dakotas. Mehar Singh just looked at us and said that was acceptable.”

A wounded casualty is evacuated for a flight to Jammu in another Dakota.

The 3.7″ howitzers were from the right section of the 4th (Hazara) Mountain Battery (F.F.). After loading, the two Dakotas took off on a bright moonlit night. Mehar Singh was hoping that the enemy gunners would have covered their guns and would be asleep. Air Marshal Grewal takes up the story, “I was to land first but our Pushong never listened to any briefings and he just cut me out and landed first, so I had to do a holding circuit behind the hills and wait.”

Mountain Guns of the 4th (Hazara) Mtn Bty (FF) being loaded in Dakota (VP-903) of No.12 Sqn.

On the ground the first Dakota had barely come to a halt when a Kumaoni officer hauled himself abroad. Pushong grabbed his khukri and they slashed the ropes with which the guns were tied, the waiting troops manhandling the guns onto the airstrip. Within minutes, VP 903 was airborne again. “There was no breeze and as the airstrip was a Kutcha place, dust was hanging over it after Pushong took off. I couldn’t wait too long and as a result I think it was the most stupid landing I ever did. I got to the threshold and cut the engines, but I couldn’t see. I was just hanging there, hoping the aircraft would touch down. Minutes later, we had cut the second gun loose and were off again…I was just getting off the ground when the enemy firing started.” But now the besieged Poonch garrison had got its own howitzers.