A history of the B-24 Liberator in IAF service

Independent India’s First War (1947-48)

During the partition of India and the creation of Pakistan, rulers of over 500 princely states were required to choose to accede to either India or Pakistan. For most of the princes the choice was obvious, one way or the other, but one ruler, Maharaja Hari Singh of Kashmir, delayed choosing, in the hope of becoming an independent country. On October 20, 1947 so-called Pukhtoon tribal raiders, in reality mostly Pakistani army personnel, invaded Kashmir and after much looting and killing reached the outskirts of Srinagar. Only then did Maharaja Hari Singh ask India for help. He got it only after he signed the accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India. The Indian Air Force (IAF) went into action and its Douglas Dakotas airlifted much-needed men and materiel into the state. IAF Spitfires and Tempests, and even Harvards, went into action in support of ground forces. Gradually the raiders were pushed back and a large part of Kashmir was recovered by India.

Make-Do Bombers aka Dakotas

At one stage of the fighting a requirement arose to bomb Pakistani positions. But there was no bomber aircraft in the IAF’s inventory. Nothing daunted, the redoubtable Air Commodore Mehar Singh, DSO, the Air Officer Commanding of the operations group in Kashmir, took recourse to his favourite Dakota. Bombs were carried within the fuselage and simply pushed out of the cargo door. With no aids or methods for aiming, the crew had to guess when to roll out the bomb. This was a hit-or-miss technique in every sense, and militarily not particularly effective.

The fighting in Kashmir ended on December 31, 1948 with a UN-brokered ceasefire. But well before then the IAF had started looking for a purpose-designed bomber aircraft. The USA tried to sell B-25 Mitchells, and the UK offered some war-surplus Lancasters, but the IAF considered both types unsuitable.

Junked B-24 Liberator Bombers

Senior IAF officers remembered that a large number of Consolidated B-24 Liberators had been abandoned in the scrap yard at Chakeri airfield, Kanpur, at the end of World War II. Most of these were former Royal Air Force (RAF) aircraft, which the USA had provided under Lend-Lease terms, which stipulated that they should not fall into anyone else’s hands after the war. Some of the abandoned Liberators may have originally belonged to the US Army Air Force and others to Royal Canadian Air Force. However their eventual disposal, as the huge Allied military establishment in India wound down after World War II, was the responsibility of the RAF.

The disposal approach taken by the RAF was to damage the aircraft to make them unusable. Bulldozers and trucks were rammed into the fuselages, which were also pierced with pickaxes. Instruments were broken and sand poured into engines. But counting the days to their return home, RAF airmen did not have their hearts in the job. IAF officers wondered if the abandoned Liberators could be salvaged to meet the IAF’s bomber requirements. Their conclusion was that salvage was possible but needed specialist support. This brought Hindustan Aircraft Limited (HAL), then a large aircraft servicing organisation (and now, as Hindustan Aeronautics Limited, a full-service aircraft design and manufacturing company), into the picture.

Aircraft Overhaul at HAL

During World War II HAL had been pressed into the war effort, overhauling Allied aircraft and assembling some fighters and bombers of US origin. HAL was the first organisation authorised to overhaul Dakotas in Asia. War exigencies had also seen HAL overhaul other aircraft types such as the Consolidated PBY Catalina. These amphibian aircraft would touch down in the waters of Bellendur Tank, a lake near the southern boundary of what today has become HAL’s Bangalore airfield. The Catalinas would taxi to the water’s edge and then lower their wheels and climb onto cement ramps built on he shoreline. (These ramps used to be visible till the mid-60s but are now sadly buried under mud and overgrowth.) The Catalinas were then towed to the nearby HAL factory for overhaul. After flight-testing and clearance the process was repeated in reverse. At the end of World War II, the RAF handed HAL back to Indian control. At last HAL could control its own destiny. When asked about salvaging B-24s, HAL readily agreed to undertake the job.

The first problem was to get the aircraft from Kanpur, where they had been abandoned, to HAL’s factory in Bangalore. The Liberators were too big to be transported by the road or rail links of the time, so the only way was to fly them. Even before undergoing full refurbishment, the Liberators had first to be made flyable enough to undertake a single ferry flight of almost 1500 kilometres. Once they arrived in Bangalore, HAL could undertake definitive refurbishment, making them fully airworthy and fit for long-term service.

HAL sent a team to Kanpur under the leadership of Mr Yelappa. He and his men surveyed the junked hulks, identified those aircraft that could be made flyable, and undertook temporary repairs by cannibalising parts from others. Some help in materials was obtained from the IAF Depot at Kanpur. But the job was done entirely by HAL personnel.

As aircraft were prepared for the ferry, a few B-24 qualified American pilots were contacted to undertake the hazardous ferry flights. They demanded so much money that hiring any of them was out of the question. Finally, the Chief Test Pilot (CTP) of HAL was asked if he would take on the job. He promptly agreed, and was offered a very handsome bonus for each aircraft ferried. When he turned this down the amount was raised even more. This was also turned down. He explained that he was already paid enough by HAL and would do the job for no payment at all in the service of the nation. This intrepid Test Pilot was Jamshed Kaikobad (Jimmy) Munshi.

Jamshed Kaikobad Munshi (1920-1988)

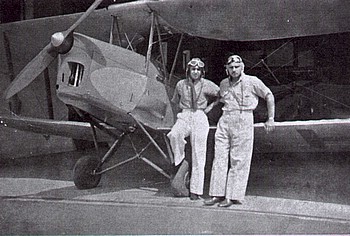

Jimmy Munshi and his younger brother Rustam always had their gaze perpetually turned towards the sky. Their father had gifted them an aircraft of their own. The family lived in Hyderabad, where much of the pioneering flying in India had taken place, as chronicled by Mrs Anuradha Reddy in her excellent book, “Aviation in the Hyderabad Dominions”. Jimmy and Rustam lived up to this local tradition. They often flew to Bombay on the pretext of picking up fuel at a lower price. What they did take in was lunch and a movie, before flying back home. They soon built up the hours required to become professional commercial pilots. Unfortunately, Rustam was killed in a flying accident in Tatanagar. But Jimmy went on to join Deccan Airways and flew DC-3s for many years. Some HAL old-timers say that it was Mr Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, then Minister for Commerce, who persuaded Jimmy to give up his lucrative airline job and join post-independence HAL as its first CTP. Apart from flight-testing various types of aircraft after overhaul, Jimmy now had the job of ferrying B-24s, temporarily patched-up by Yelappa’s men, from Kanpur to Bangalore.

|

Jamshed and Rustam Munshi with a Tigermoth owned by them. Rustam died while flying with No.3 Squadron during WW2. |

Flying the Liberators

Far from having flown B-24s, Jimmy probably had no experience of any four-engine aircraft. The Liberators therefore were a real challenge. And he obviously relished it. His first task was to find a manual for the aircraft. In accordance with US and British practice, each aircraft should have carried its own copy of the Flight Manual. But preservation of the manuals had clearly not been a priority, when the aircraft had been abandoned at Kanpur. Jimmy rummaged around in many wrecked cockpits, sometimes finding just a few pages, and gradually assembled a workable manual. When he was ready for flight, the manual was placed in his lap and referred to as required. At take off it was handed over to one of the HAL men, usually the flight engineer, riding in the aircraft to read out checklists for each stage of flight.

Jimmy already had some familiarity with the Pratt & Whitney 1800-43 engines of the Liberators, as they came from the same family as engines of the DC-3s he had flown before. It is said that he would open full power on the four engines, and if nothing blew up, do some fast taxying to check that engines were delivering adequate power and that the brakes functioned properly. He was then off on a direct flight to Bangalore with undercarriage left down throughout. Only one flight is known to have been scary. There was a small fire in the fuselage just behind the pilot’s seat. Fortunately the HAL crew was serving coffee at the time. The entire contents of the flasks were poured on the fire, to successfully put it out. A flight was described by two IAF flight cadets who hitched a ride in one of the B-24s, with no understanding of what they were getting into. Their first surprise was that the co-pilot’s seat was occupied by Jimmy’s wife in a fur coat. She was well prepared for the draughty and cold cabin of the B-34. As the aircraft taxied out a front windshield glass cracked. Jimmy taxied back for quick repairs. HAL’s engineers put some dope on the glass, stuck fabric on it and declared the aircraft flyable. Fortunately nothing worse happened and the cadets slept all the way through to Bangalore.

Jimmy ferried a total of 42 B-24s patched-up for flying by Yelappa and his men. All the ferried B-24s were overhauled and refurbished to long-term flyable standard. Jimmy then tested and cleared them for service. According to some HAL engineers, a visiting American pilot once flew one of these aircraft and complimented HAL on the quality of work done on it. He said that the refurbished aircraft was even better than some he had flown earlier.

When the American’s discovered that India had acquired serviceable Liberators there was consternation, and a suspicion that they had been bought clandestinely. They were unhappy that they had no logistic or other control on these fairly potent bombers No one could figure out who had sold them to India. An American team was invited to see what IAF and HAL were up to. The team went away satisfied that there were no underhanded dealings. Soon afterwards, very graciously, the RAF offered any help that India might need in handling the refurbished aircraft. Two experienced teams came to Poona to help convert and train IAF crews in operations on B-24s.

Liberators in Service

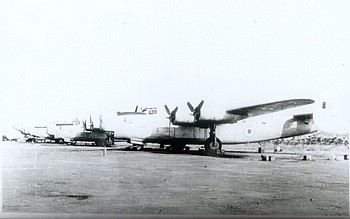

The IAF had its bombers at last. No 5 Squadron was equipped on November 2, 1948 with the first six Liberators delivered by HAL. Eventually the Squadron received its full contingent of 16 aircraft. No. 6 Squadron had been raised at Tiruchirapally on 1st December 1942 under the command of Mehar Singh (the same redoubtable officer who had pressed Dakotas into service as bombers in Kashmir), then a Squadron Leader. In January 1951, after having been stood down since Independence and Partition, it was re-raised and equipped with sixteen refurbished Liberators. No 16 Squadron was established with only two or three aircraft on October 15, 1951 as a Liberator-equipped training unit. No Liberators were ever used in anger.

|

|

| Unknown Liberator after a botched 3 engine practice landing at Poona in the fifties. One crewmember was found missing after the crash, having run a 100 yard dash as fast as he could! | |

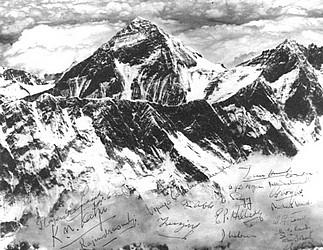

In addition, two recovered C-87 aircraft formed No 102 Survey Flight. C-87s were modified Liberators with most of the external protrusions removed. The cabin area was meant for cargo. The C-87 was aerodynamically cleaner, and therefore about 20 knots faster, than the B-24. It was often called The Liberator Express. The C-87s were used for survey work to update old maps and produce new ones of uncharted areas. One aircraft was also employed for photographing Mount Everest.

No 5 and 16 Squadrons traded in their B-24s for the British Canberra bomber-interdictor aircraft in 1957. But the Liberators of No 6 Squadron continued flying in the task of maritime reconnaissance. Most of their aircraft were fitted with the ASV-15 radar with a retractable radome in the bay where the ball turret had originally been located. Sonobuoys and depth charges were their typical load. No 6 Squadron also participated in the takeover of the Portuguese colonies in India in 1961. It flew reconnaissance missions along the sea-lanes approaching Diu and Daman. On December 18, 1961, Liberators of No 6 Squadron dropped surrender leaflets over Goa. The Squadron also carried out maritime patrols during the 1965 Indo-Pak War. The Liberators retired from IAF service in 1968. Thus the Indian Air Force was the world’s last air force to fly the type.

Rocking Parliament and Expedition to Mt Everest

In the spring of 1953, the IAF decided to display its prowess through a public Fire Power Demonstration. The (now abandoned) firing range south of Delhi at Tilpat near Faridabad was the venue. One of the display highlights was to be a demonstration of the awesome power of stick bombing from Liberators. Formations of B-24s were to drop sticks of 500-pound bombs in a show of carpet-bombing. During a rehearsal with live bombs the delivery was perfect. Most of the bombs fell in a straight line. The trouble was that the line pointed straight to Parliament House in Delhi. Although it was several miles away, because of a fortuitous combination of timing and geological factors, the edifice shook as if a major earthquake had hit it. Most of the MPs ran out, displaying a turn of speed not seen during today’s walkouts. When the cause was discovered the Prime Minister, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, was livid and wanted the exercise cancelled. The Chief of Air Staff was soon on the mat. But the Scientific Advisor to the Defence Minister came to his rescue. He explained to the PM that his staff had studied the event very thoroughly all night. They had concluded that the repetition of a similar occurrence was not possible. Pt Nehru accepted this view and permitted the final Fire Power Demonstration to go ahead. Since high expectations had been raised by the radio and press, large crowds of people tried to see the show. Extensive traffic jams resulted, despite the relatively small number of cars in Delhi at the time. Many people never got anywhere near the Tilpat Range. They had to be content with only hearing the noise of the exploding bombs.

When in the summer of 1953 Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay were about to reach the summit of Mount Everest, it was decided to take aerial pictures of them planting flags on the summit. A Liberator Express of 102 Survey Flight was launched, on the day of Hillary and Tenzing’s summit attempt, with several press photographers on board. Since the aircraft would have had to climb to nearly 29,000 feet (8.85 km), oxygen for everyone on board was essential. The C-87s were not designed for passengers. Hence oxygen masks had to be passed from hand to hand among the photographers. This gave each of them a chance to draw a few long breaths and hand them over to the next person. After the C-87 was well on its way, there was a sudden fear that the thunderous noise of its four engines could start a dangerous avalanche. Just in time, the aircraft was recalled, much to the disappointment of the photographers on board. Pictures of Mount Everest were taken on a later flight, once the expedition was clear, and some stunning shots were published around the world. The C-87 variant of the IAF’s Liberators was responsible for achieving this.

Surviving Liberators

After their retirement from IAF, many B-24s were sold for scrap. When the news spread round the world, many requests were received for aircraft to be sold or gifted to museums. Today five Liberators resurrected from Kanpur are known to be in museums in the USA, Canada and the UK.

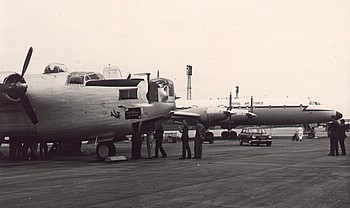

|

|

| The Liberator HE-809 donated to the RAF Museum at the end of its long ferry flight. The Story of its journey is told by Wg Cdr Chopra in Flypast Magazine’s August 98 issue | |

One of these, at the Collings Foundation of the USA, was operated as a flying museum. But for the hard work and dedication of HAL’s Yelappa and his team, the CTP, and its personnel involved in overhauls, the world would have been poorer by more than half the surviving samples of this famous WW II aircraft.

|

|

| (Left) IAF B-24 in Tucson and a nostalgic pilot , Gp Capt K Advani, who flew the same aircraft in IAF service as a young Pilot Officer (Right) A close up of the Pima Paissano, on display at Tucson. | |

All Photographs from the Authors personal collection.

Recommended Links:

-

Fail, J E H : “The Survivors”, an article on former SEAC Liberator survivors at http://www.rquirk.com/fail/article/Failsurv.htm

-

Fail, J E H : 322MU scrapping of B-24 Liberators at http://www.rquirk.com/fail/322mu/322mu.htm

-

Sree Kumar K : “The Indian Inheritance of the B-24 Liberator” at http://www.warbirdsofindia.com/ovb24.html

-

Kondath V Wg Cdr : “Liberator Tales” at http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/IAF/History/1950s/Kondath02.html